California Wildfire Season 2016

Climate disruption in California—including record high temperatures, ongoing drought, tree die off and bark beetle outbreaks—has increased the state's wildfire risk by extending wildfire seasons, expanding at risk areas, and increasing fire size.

Ahead of the 2016 fire season, storms associated with the strong 2015-2016 El Niño alleviated some drought concerns, but rain and snowfall totals were insufficient to lift California out of drought. Extreme heat and dryness ultimately defined California's 2016 wildfire season, fueling explosive, large, and costly fires.

Southern California in particular experienced little relief due to a persistent high-pressure ridge that blocked El Niño storms from hitting the region.

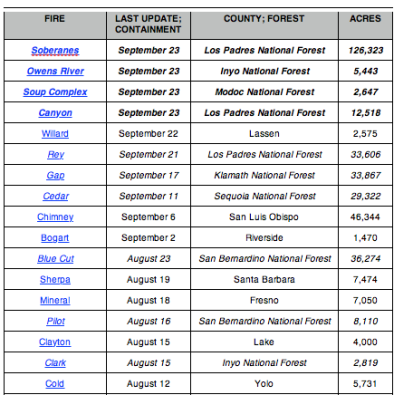

The Soberanes fire in Monterey County, which began in July and burned for three months, was the biggest fire of the the season and costliest firefight in US history, costing $260 million. Fourteen of the state's 20 largest fires on record have burned since 2000.

Heat and drought increase wildfire risk through longer seasons, reduced snowpack and increasing pine beetle outbreaks

Extreme heat and years of ongoing drought, both linked to climate change, are increasing wildfire risk in California by contributing to the frequency and severity of wildfires in recent decades.[2]

California had its warmest summer on record in 2016, with a statewide average temperature of 75.5°F, or 3.3°F above average. Combined with diminished precipitation, high temperatures in California are causing soils and vegetation to lose moisture earlier in the spring and stay dry later in the fall, meaning the landscape is flammable for more of the year.[1] Extreme heat and years of ongoing drought are both linked to climate change and are increasing California's wildfire risk by contributing to the frequency and severity of wildfires in recent decades.[2]

I don’t ever envision the fire season ever shutting down again. In areas like southern California, the deployment of staff and resources to deal with wildfire is going to become a permanent feature rather than a seasonal one. – Dr. Keith Gilless, Chair of CA State Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, Dean of UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources [3]

The conditions for fire are getting worse. There are longer fire seasons, and the fire seasons that are more extreme are happening more frequently. All of the conditions are there for having more severe fire seasons. — Mark Cochrane, a fire ecologist at South Dakota State University [9]

Recently observed heat and precipitation patterns in California have also caused snowpack to melt earlier, depriving ecosystems of a valuable source of moisture as summer temperatures dry out the landscape. Snowpack levels stood at or near record lows during the winters of 2013, 2014 and 2015.[4] Thanks to a strong El Niño that brought near average precipitation to the northern California, the statewide April 1 snowpack measurement in 2016 showed state water resources at 87 percent of the long-term average; however, the snowpack was not sufficient to undo water deficits caused by years of drought.[5]

Climate change is also affecting the prevalence and distribution of bark beetles, because warmer winters allow bark beetles to breed more frequently and successfully.[6][7] Bark beetles can damage whole regions of forest by depositing eggs under the bark of pine trees that hatch into larval grubs and consume the trees. Scientists are still working to understand the complex interactions between bark beetles and forest fires, but the beetles are increasing fire risk through altering forest structure and wildfire fuel sources. There is also evidence showing that the dead trees that bark beetles leave behind make crown fires—or fires that spread from treetop to treetop—more likely.[8]

The 2016 California wildfire season picked up where previous years left off

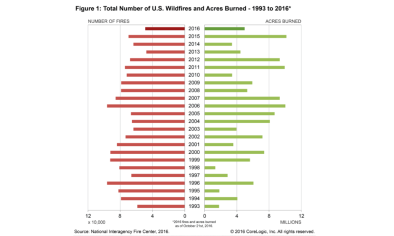

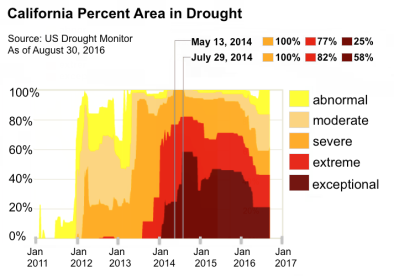

In 2014, California saw 100 percent of its territory pass through drought conditions ranked “severe” or worse for the first time. The year ended as the state’s driest and warmest on records dating back to 1895. In 2015, California experienced its second-driest and second-warmest year on record. Two wildfires during California's 2015 wildfire season—the Valley and Butte Fires—ranked among the top 10 most destructive fires in state history.[10] At 151,623 acres, the Rough Fire of 2015 became the thirteenth largest in terms of overall acres burned, and it was also the thirteenth fire since 2000 to rank among California's top 20 largest wildfires in records dating back to 1932.[11]

The 2016 wildfire season picked up where 2015 left off. The summer of 2016, from June-August, was California's warmest on record, with an average temperature 3.3°F (1.8°C) above the 1901-2000 base period.

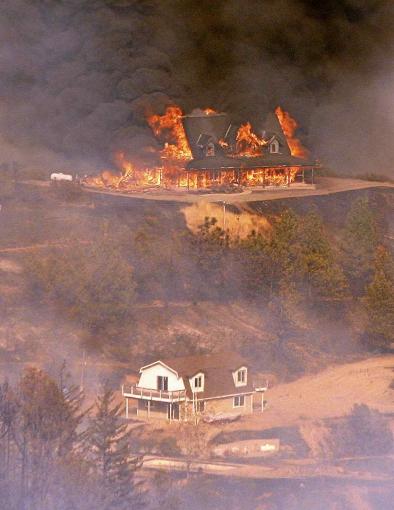

Many large wildfires during California's 2016 season were exacerbated by dried out fuels and record-breaking temperatures, including the record-breaking Soberanes Fire. As of September 23, 2016, the Soberanes Fire had burned 126,323 acres and is the fourteenth fire since 2000 to rank among California's top 20 wildfires.[11] It is also the single costliest wildfire in US history to suppress.[12] Other notable fires during the 2016 season include: the Erskine Fire, the Sand Fire, and the Blue Cut Fire.

The record El Niño of 2015-2016 did not end the California drought

The presence of a strong El Niño in 2016 heightened anticipation of a drought-busting rain and snow season, but the results were mixed, and ultimately the observed rain and snowfall was not sufficient to lift California out of the drought that has prevailed since 2011. El Niño helped steer enough rain and snow to the the northern part of California to help cut into the multi-year drought that’s plagued the state, but southern California did not receive nearly as much precipitation and dry conditions already began creeping back in April.[13][14]

Rain and snowfall totals during the winter of 2015-2016 were barely above the long-term average, and evidence suggests groundwater levels in California’s Central Valley will continue to decline in 2016.[15]

Southern California, in particular, received little relief from the persistent hot and dry conditions that increase wildfire risk. Warmer than average temperatures off Baja California and persistent high pressure air patterns blocked most of the precipitation from the strong 2015-2016 El Niño from reaching Southern California.[16] The exceptionally dry conditions in Southern California help to explain the explosive spread of the Blue Cut Fire, which consumed 30,000 acres in 24 hours and destroyed 105 homes.[17]

One of the things that we’re seeing is that the fires are burning in really an unprecedented fashion...It’s to the point where explosive fire growth is the new normal this year, and that’s a challenge for all of us to take on. – Glenn Barley, the San Bernardino unit chief of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) [21]

The fingerprint of climate change has been identified in California's wildfires

A formal modeling analysis has identified the fingerprint of global warming in California's wildfires, reporting that, "an increase in fire risk in California is attributable to human-induced climate change." [18]

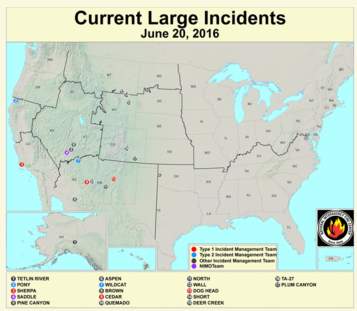

Looking across the region: according to the US National Academy of Sciences, there has been a fourfold increase over the last 30 years in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West.[19] The length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[19][20] More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[20]

Sierra foothills face high fire risk due to pine beetle infestation

Higher temperatures and drought have weakened trees and increased their susceptibility to the bark beetle, resulting in tens of millions of dead trees across California that have further fueled wildfires.

The US Forest Service announced in June 2016 that 66 million trees have died since 2010 due to pine beetle infestation linked to years of drought and warmer temperatures.[22] The announcement was based on a May 2016 survey that identified 26 million additional dead trees in six southern Sierra counties (Fresno, Kern, Madera, Mariposa, Tuolumne and Tulare) since the October 2015 survey.[22]

Central California is especially vulnerable to wildfires due to a severe pine beetle infestation that, along with ongoing drought, has brought a high level of plant mortality to many areas in the region. Aerial surveys indicate parts of the Sierra Foothills between 2,000 to 6,000 feet have suffered over 50 percent tree mortality, especially in Ponderosa Pines.[23] Many stands have yet to drop their needles and thousands of acres in the Sierras are primed for large fires from a fuels standpoint.[23]

Central California is especially vulnerable to wildfires due to a severe pine beetle infestation that, along with ongoing drought, has brought a high level of plant mortality to many areas in the region. Aerial surveys indicate parts of the Sierra Foothills between 2,000 to 6,000 feet have suffered over 50 percent tree mortality, especially in Ponderosa Pines.[23] Many stands have yet to drop their needles and thousands of acres in the Sierras are primed for large fires from a fuels standpoint.[23]

The 2015 California Forest Health Highlights Report found that drought-stricken and fire-damaged trees fueled bark beetle outbreaks of epidemic proportions in areas of coastal and southern California, as well as throughout the central and southern Sierra Nevada range.[24]

Related Content