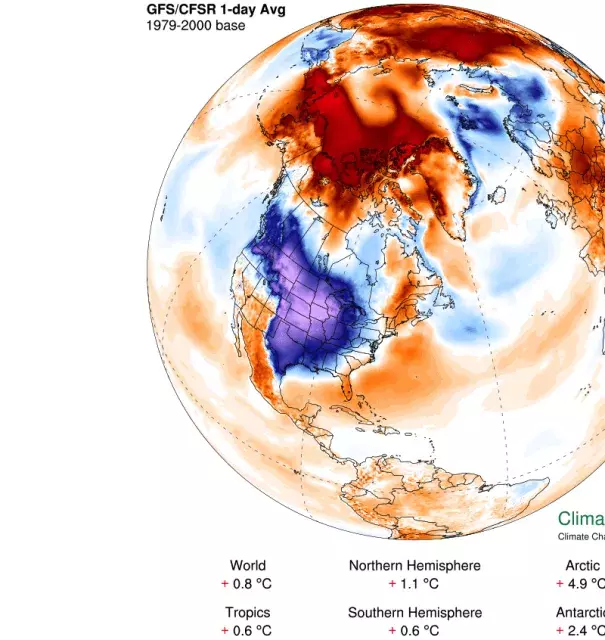

Polar Vortex Dip and US Arctic Invasion March 2019

In early March 2019, the polar vortex—the very cold air mass that normally circulates in the Arctic—bulged down into North America bringing temperatures well below freezing. The Arctic blast is a repeat of what happened in January, when the polar vortex broke into pieces, with a fragment dipping south and creating dangerously cold conditions in the Lower 48 states.

While climate change warms the planet as whole, it also disrupts regional weather patterns, sometimes displacing cold air to the south. The overall warming trend continues but cold conditions can move. The abnormal behavior of the polar vortex is caused by a dip in the jet stream and is associated with a warm air mass that pulsed north into Alaska. Temperatures in the Arctic were about 10°F above average.

The warm weather observed further north in parallel to cold conditions in the continental US are consistent with the pattern of disruption expected due to climate change.

Climate science at a glance

-

Climate change disrupts regional weather patterns and can bring cold further south while warm air can travel further north.

-

The Arctic is warming twice to three times as fast as the global rate due to the unique feedbacks in the Arctic climate system—a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification.[1]

-

Disruption via Arctic warming affects weather patterns in the mid-latitudes, e.g. the continental United States.

-

Global warming has now gone beyond adding energy to the thermodynamic dimension of our climate and is now the patterns of atmospheric circulation, including the jet stream.

-

Atmospheric blocking due to anomalous, persistent, meandering of the jet stream often causes weather extremes in the midlatitudes.[2]

Background information

Climate change doesn’t mean no more cold weather anywhere ever. It means more warm weather than cold, and that’s what we’ve seen.

The long-term warming trend is clear and undeniable. The past four years have been the hottest on record for the globe, and there hasn’t been a cooler-than-average year in three decades. We’re seeing a lot more record hot weather than record cold, by about a 2 to 1 margin. Cold snaps in the Upper Midwest have become much less frequent. The recent National Climate Assessment explained how warmer winters are allowing pests to kill more trees, which leads to more wildfires; are already decreasing snowpack and costing the winter recreation industry money; and allowed for the northward spread of Lyme disease, among others.

But as NOAA has explained, there’s actually good reason to expect heavier snow storms in some locations, even as we experience less overall cold. And just because the globe is warming overall doesn't mean cold temperatures have been completely eradicated.

There is significant evidence that this particular type of cold snap, known as an extension of the polar vortex, may be a symptom of climate change.

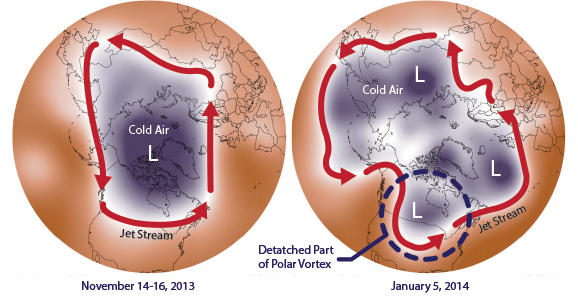

The extremely cold air above the Arctic in winter is typically corralled by the polar vortex jet stream. But there is mounting evidence that the rapid warming of the Arctic is making for a more wavy jet stream, with waves that move more slowly across the globe. When the jet stream gets wavy, cold Arctic air “falls” down into lower latitudes — sometimes into the U.S. Thee link between a slow, wavy jet-stream and extreme U.S. weather is well-established.

We may see more unusual polar vortex behavior in the future.

The Arctic is warming twice to three times as fast as the global rate due to the unique features in the Arctic climate system—a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. The rapid rise in Arctic temperatures relative to the slower warming elsewhere may be leading to a more meandering jet stream. A warmer Arctic may be causing wintertime weather to get "stuck" more often, with cold air diving south and warm air heading north.

Climate signal #1: Arctic amplification

The Arctic has warmed about twice as fast as the rest of the world. In some places, winter temperatures are as much as 7°F, or almost 4°C warmer than they were just 50 years ago.

Arctic warming affects weather patterns in the mid-latitudes, where most people live. That's because of the jet stream—a narrow band of strong winds high up in the atmosphere that pushes weather systems along. The jet stream is powered by the temperature difference between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes, and this difference is shrinking as the Arctic warms. Scientists suspect this may be making the jet stream slow down and meander, rather than speeding around the planet as it usually does.

Arctic warming affects weather patterns in the mid-latitudes, where most people live. That's because of the jet stream—a narrow band of strong winds high up in the atmosphere that pushes weather systems along. The jet stream is powered by the temperature difference between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes, and this difference is shrinking as the Arctic warms. Scientists suspect this may be making the jet stream slow down and meander, rather than speeding around the planet as it usually does.

Models report that cold weather Arctic invasions into the eastern US grow more intense in a warming world—a phenomenon of climate disruption sometimes popularly referred to as "global weirding."

Observations consistent with climate signal #1

- On March 4, dozens of record lows were set all the way from Washington state to Texas.[3]

-

An all-time record low for the entire state of Montana may have been set at Elk Park the morning of March 4 when the temperature fell to minus 46°F.[4]

-

Two cities in Montana set all-time record lows for the month of March on /march 3, including Miles City (minus 31°F) and Livingston (minus 27°F).[4]

-

Chicago fell below zero on March 4, something that has happened only eight other March days on record at O'Hare Airport.[4]

-

Daily record lows for March 4 were set in Duluth, Minnesota (minus 19°F), and Indianapolis (2°F - tie).[4]

Climate signal #2: Atmospheric blocking increase

Wintertime circulation is likely getting "stuck" more often due to a warmer Arctic.

Atmospheric blocking occurs when waviness in the jet stream causes congestion. Blocking events are associated with long-lasting and slow-moving high-pressure systems that "block" westerly winds in the mid- and high-latitudes, causing the normal eastward progress of weather systems to stall. A major block can produce long stretches of blazing heat in the summer or bitter cold in the winter.[5]

Observations consistent with climate signal #2

- Temperatures in Great Falls, Montana didn't go above 0°F for several days.[3]