Western Wildfire Season 2021

The fingerprints of climate change were on the 2021 fire season - the second season in a row of devastating wildfires in the western US. Below average mountain snowpack, a series of early summer record-breaking heatwaves, and continued drought conditions contributed to the record-breaking season. California's Dixie fire is the largest single (non-complex) fire in California's history, and burned just under 1,000,000 acres – a mark only broken once in California’s history, just last year, by the August Complex Fire. Thanks to climate change, the western US is especially primed for fires to undergo rapid increases in coverage and intensity shortly after they start. This devastating wildfire season came to a close after an extremely powerful atmospheric river produced flooding rain in late October.

Climate science at a glance

- There is clear and mounting evidence that climate change is influencing—and will continue to influence—fire activity in the western US.

- Climate change makes it more likely that fires turn into catastrophic blazes through warmer temperatures, increasing the amount of fuel (dried vegetation) available, and reducing water availability through earlier snowmelt and higher evaporation.

- The frequency of hot, dry, and windy weather has increased in much of the US, meaning fires can quickly get out of control.[1]

- Climate change has doubled the area burned in the western US.[2]

- In California alone, there has been a fivefold increase in burned area extent in forests since 1972, mainly due to more than an eightfold increase in summer forest-fire extent due to warmer and drier conditions.

- The fire season has increased by more than two months in the western US, largely due to climate change.[3]

- California fires are burning at higher elevations than ever, creating new dangers.

- Climate change has doubled the frequency of autumn days with extreme fire weather conditions in California.[4]

Background information about the 2021 western wildfire season

What factors contribute to worsening wildfires in the western US?

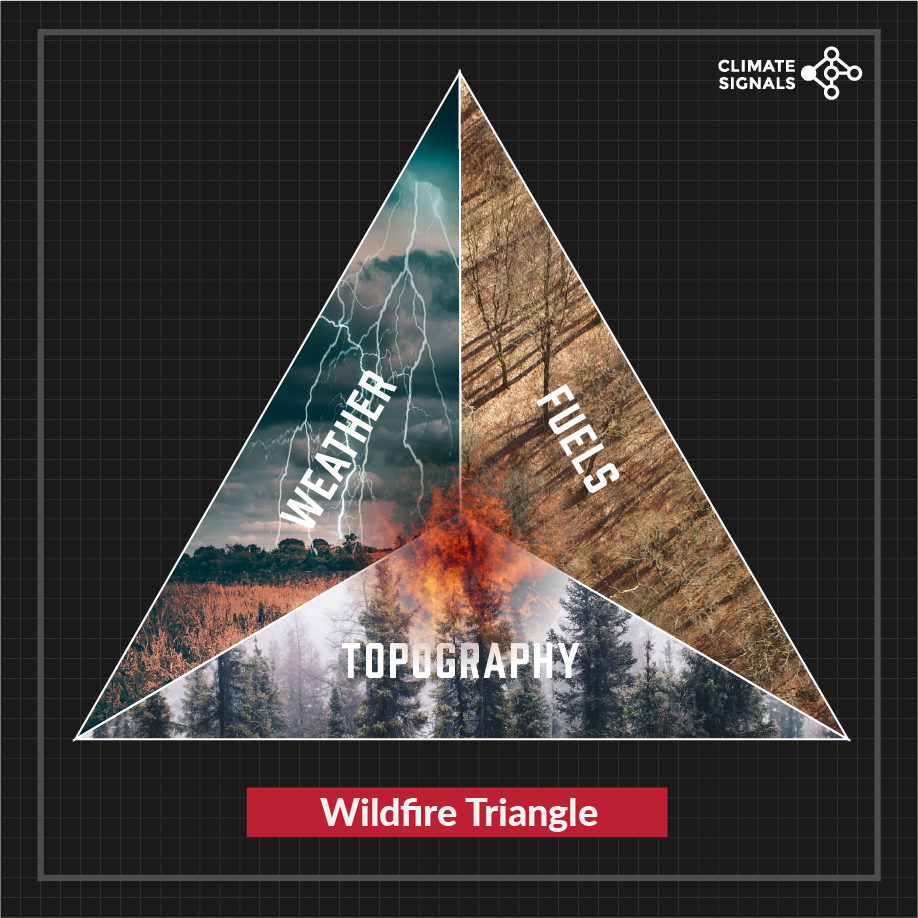

Wildfire disasters are due to the combination of climate change, human land-use and forest management, which can make fires more severe, and the exposure to and vulnerability of populations to fires.[5] Fire officials explain wildfire behavior using the fire triangle, pictured right. Wildfires are driven by three elements: topography (mountainous versus flat), vegetation (the fuel source), and weather. As topography and weather generally cannot be controlled, most fire prevention in wildlands focuses on removing dry vegetation and encouraging healthier ecosystems which won’t burn as easily. In some regions, forest mismanagement has increased wildfire risk.

Wildfire disasters are due to the combination of climate change, human land-use and forest management, which can make fires more severe, and the exposure to and vulnerability of populations to fires.[5] Fire officials explain wildfire behavior using the fire triangle, pictured right. Wildfires are driven by three elements: topography (mountainous versus flat), vegetation (the fuel source), and weather. As topography and weather generally cannot be controlled, most fire prevention in wildlands focuses on removing dry vegetation and encouraging healthier ecosystems which won’t burn as easily. In some regions, forest mismanagement has increased wildfire risk.

What were recent western wildfire seasons like?

Climate change was a key driver of the unprecedented fires that caused significant damage and devastation across the western US during the 2020 fire season. Rapid snowmelt in May, early season heat waves in late spring, the absence of the Southwest monsoon, anomalously warm seasonal temperatures, record heat waves in early fall, the hottest August through October period in western US history, and very high vapor pressure deficits had the effect of drawing moisture out of the fuels, priming the environment for explosive fire behavior.

In August, record heat, low humidity, and widespread dry lightning spawned nearly 1,000 fires in California. The situation escalated in September when seasonal offshore winds fanned the flames. [6] occurred in 2020, including the August Complex Fire, the largest fire in state history at 1.03-million acres. In early September, explosive fires in Oregon burned 900,000 acres in three days, almost double the amount that typically burns in an entire year. Washington state, which saw an average of 300,000 acres burn during the previous five years, saw 500,000 acres burn in just a few days. By mid-October, the Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado had grown to become the largest fire in state history. Colorado and California set new records for total acres burned in a single season. By December 31, 2020, the National Interagency Fire Center reported that US wildfires burned 10.27 million acres – the highest yearly total since accurate records began in 1983.

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signal #1: Land surface temperature increase

Humans spark most fires, but global warming makes it much riskier to have that spark light a fire by increasing the size, frequency, intensity and seasonality of western wildfires. Between 1901 and 2016, the average annual temperatures in the Southwest and Northwest increased by 1.6°F (0.9ºC), and nearly 2°F (1.1°C) respectively.

Hotter and drier conditions driven by global warming have doubled the area burned in the western US and increased the fire season in the region by more than two months.[2]

Observations consistent with climate signal #1:

-

California, Nevada, and Oregon experienced their hottest summer (Jun-Aug) on record in 2021 at 5.1°F, 5.5°F, and 5.7°F above the 20th century average respectively. Other western states were also exceptionally hot: Washington's summer was the second hottest at 5.0°F above the 20th century average, and Arizona's summer tied for second hottest at 3.3°F above.

-

By early July 2021, twice as many acres had burned in California compared to the same time frame in 2020 (January - early July).

-

By late July 2021, the Bootleg Fire in Oregon had burned over 400,000 acres, and grew large enough to influence local weather patterns.

-

On August 30, the Caldor Fire breached Echo Summit, crossing the Sierra Nevada and posing a direct threat to the population centers around Lake Tahoe, forcing more than 50,000 people to evacuate. A wildfire has crossed over the Sierra Nevada just once before in recorded history: less than two weeks ago the Dixie Fire crossed the mountain range farther north.

Climate signal #2: Extreme heat and heat waves

Due to climate change, extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent, and this spells trouble for wildfire season in the western US. On a hot summer day, a small spark can ignite a raging wildfire, and data shows that many more wildfires burn in hotter years.[3]

Scientists have found a direct link between increasing heat extremes in the West and human-caused climate change.[7] As the West heats up, conditions are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[8] During the period 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West, and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[9][10]

Observations consistent with climate signal #2

- Las Vegas tied its all-time record high of 117°F on July 10th. That record was set in 1942, but has been tied three other times - all in the last 20 years - 2005, 2013, and 2017.

- Canada saw its highest temperature ever recorded on June 27, when Lytton in British Columbia surged to 115.9°F (46.6°C), beating the previous record of 113°F (45°C) by 2.9°F (1.6°C).

- Seattle set an all-time record high of 104°F on June 27th.

- Phoenix, AZ had its longest streak of 115°F+ heat on record with 6 consecutive days of 115°F+ high temperatures (June 15-20), including a high of 118°F on June 17th. Records in Phoenix go back to August 1865.

Climate signal #3: Drought risk increase

The most direct link between climate change and fire is through how dry fuels get. What we've seen in the Western United States is that fuel dryness during the fire season explains around three quarters of the year-to-year variability in burned area extent. That has the effect of drawing moisture out of the fuels and priming the environment. Climate change plays a role through increasing the rate at which the temperatures warm, increasing the rate at which they draw moisture out of fuels. Drier conditions can allow fires to spread quickly.

Underlying year-to-year variability, research shows the Western United States in the midst of an extreme megadrought, among the worst in recorded history, and rising temperatures due to human-caused climate change are responsible for about half the pace and severity of the drought.[11]

Observations consistent with climate signal #3

-

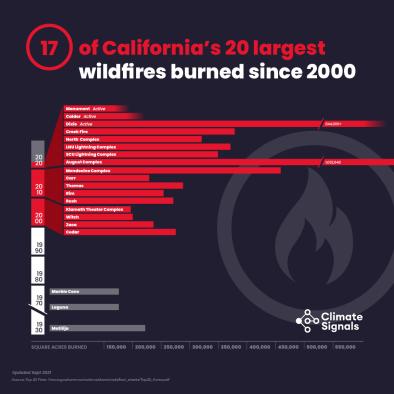

Hot and dry conditions are fueling large wildfires. Four of California's 20 largest fires on record have occurred during the 2021 season, including the Dixie fire, the single largest blaze ever recorded. The Dixie fire is anticipated to breach the 1,000,000 acre mark – a mark only broken once in California’s history, just last year, by the August Complex Fire.

-

Under extreme drought conditions, August wildfires in Northern California burned rapidly and with extreme severity, traveling up to 8 miles in a single day.

-

In early July 2021, large swaths of the western US were in "exceptional drought", the worst category, including Utah (65%), Arizona (58%), Nevada (41%) and California (33%).

-

By January 2021, water levels in Lake Powell, the river’s second-largest reservoir, dropped to unprecedented depths, triggering a drought contingency plan for the first time for the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. On Aug. 16, the federal government declared a Colorado River water shortage for the first time when Lake Mead’s water level dropped to only 35% of full capacity. The declaration triggers cuts in water supply that will pose major challenges for regional farmers.

Climate signal #4: Lightning risk increase

Lightning occurs during storms with strong updrafts. During these storms, charged ice particles in clouds collide, generating an electric field. If the field is strong enough, electricity can arc to the ground as lightning, which can ignite dry vegetation. Nationwide, about 15 percent of wildfires start this way.

Strikes across the United States are expected to increase with climate change, as warmer air carries more water vapor, which provides the fuel for strong updraft conditions. A 2014 study estimated that strikes could increase by about 12 percent per 1.8°F (1°C) of warming, or by about 50 percent by 2100.

Observations consistent with climate signal #4

- In August 2021, lighting sparked dozens of fires in Washington state, in just one 24 hour period.

Climate signals #5 and #6: Snowpack decline and snowpack melting earlier and/or faster

Rapid, early snowmelt means a longer dry season, drier vegetation and larger fires in mid- and high-elevation forests. Warmer springs and summers, and the resulting shifts in snowmelt timing, have helped to drive marked increases in burned area in Western forests since the mid-1980s.[2]

This year, like the previous five to 10 years, has water managers working their worry beads.

Bill Patzert, climatologist

Observations consistent with climate signals #5 and #6

-

On March 23, 2021, California's statewide snowpack was at 63 percent of the historical average for April 1.

-

By mid-June 2021, nearly all of the SNOTEL sites in the western region reported less than 50 percent of their normal snow-to-water equivalent amounts. Many were at or near 0%.

Related Content