Because of climate change, hurricanes are raining harder and may be growing stronger more quickly

Two studies published in the past week have troubling implications for the effects hurricanes have on society because of climate change, now and in the future.

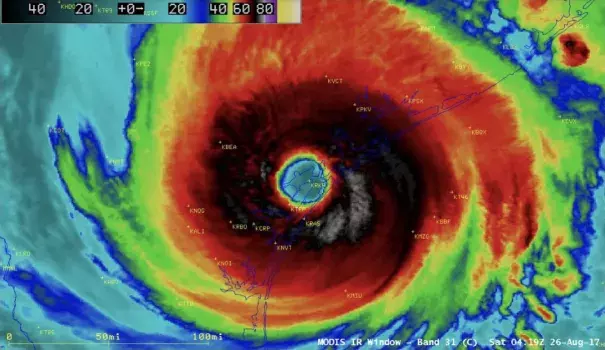

One directly links Hurricane Harvey’s disastrous rains to the amount of heat stored in the ocean, which was record-setting before the storm plowed into Texas last year. The other shows an increasing trend in storms that are becoming really strong, really fast.

Storms that unload more rain and explosively intensify cause more destruction and suffering, as the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season painfully made clear. Harvey, Irma and Maria each ranked among the five costliest hurricanes on record.

...

The study determined that the energy released into the atmosphere from Harvey’s rainfall matched the amount of energy which was removed from the ocean in the storm’s wake. In other words, the study found that the amount of heat stored in the ocean is directly related to how much rain a storm can unload.

The implication is that if climate change, driven by increasing greenhouse gases from human activity, increases the heat content of the ocean, storms passing over it will be able to draw ever more moisture that they can unload as rain.

...

Rapid intensification events on the rise

During the 2017 hurricane season, Harvey, Irma, Jose and Maria all underwent what is known as “rapid intensification.” This means their peak wind speed rose at a torrid pace, by at least 29 mph in 24 hours, according to one definition (alternative definitions vary).

Maria, for example, strengthened from a Category 1 to Category 4 storm on the Saffir-Simpson wind scale in 12 hours. The storm would go on to decimate the island of Dominica and, ultimately, St. Croix and Puerto Rico.

A study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters found that the magnitude of these rapid intensification events increased from 1986 to 2015 in the central and eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean.

Related Content