Climate change doubled the likelihood of the New South Wales heatwave

The heatwave that engulfed southeastern Australia at the end of last week has seen heat records continue to tumble like Jenga blocks.

On Saturday February 11, as New South Wales suffered through the heatwave’s peak, temperatures soared to 47℃ in Richmond, 50km northwest of Sydney, while 87 fires raged across the state amid catastrophic fire conditions.

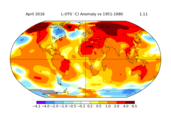

On that day, most of NSW experienced temperatures at least 12℃ above normal for this time of year. In White Cliffs, the overnight minimum was 34.2℃, breaking the station’s 102-year-old record.

On Friday, the average maximum temperature right across NSW hit 42.4℃, beating the previous record of 42℃. The new record stood for all of 24 hours before it was smashed again on Saturday, as the whole state averaged 44.02℃ at its peak. At this time, NSW was the hottest place on Earth.

...

The useful thing scientifically about heatwaves is that we can estimate the role that climate change plays in these individual events. This is a relatively new field known as “event attribution”, which has grown and improved significantly over the past decade.

Using the Weather@Home climate model, we looked at the role of human-induced climate change in this latest heatwave, as we have for other events before.

We compared the likelihood of such a heatwave in model simulations that factor in human greenhouse gas emissions, compared with simulations in which there is no such human influence. Since 2017 has only just begun, we used model runs representing 2014, which was similarly an El Niño-neutral year, while also experiencing similar levels of human influence on the climate.

Based on this analysis, we found that heatwaves at least as hot as this one are now twice as likely to occur. In the current climate, a heatwave of this severity and extent occurs, on average, once every 120 years, so is still quite rare. However, without human-induced climate change, this heatwave would only occur once every 240 years.

In other words, the waiting time for the recent east Australian heatwave has halved. As climate change worsens in the coming decades, the waiting time will reduce even further.

Related Content