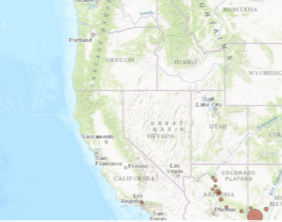

Western Wildfire Season 2018

Higher temperatures, reduced snowpack, increased drought risk, and longer warm seasons are increasing wildfire activity in the western United States.

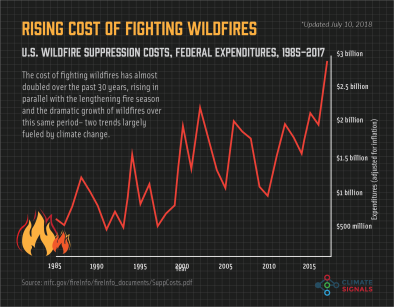

From 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West; the length of the fire season expanded by 2.5 months; and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[1]

In late July, the Carr Fire in Shasta and Redding California exploded to 28,800 acres (45 square miles) “taking down everything in its path."[2] The fire began late on July 23 and tripled in size overnight on July 26 and 27 amid scorching temperatures, low humidity and windy conditions.[2] Temperatures in Redding on July 27 were expected to reach 111°F, adding to the challenges facing firefighters as they fight for control.[3]

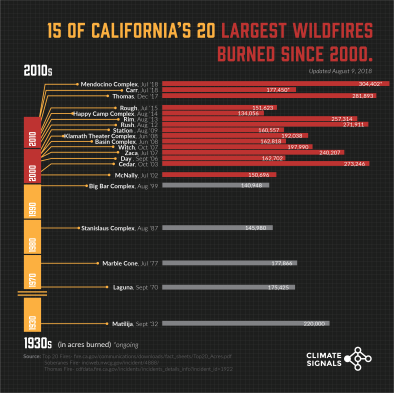

Shortly after, only about seven months after the Thomas Fire became the largest wildfire in California history, the Mendocino Complex Fire beat that record. Fifteen of California's top 20 largest wildfires on record have occurred since 2000.

Climate science at a glance

-

Human-caused climate change is increasing wildfire activity across forested land in the western United States.[1][2]

-

Since 1970, temperatures in the American West have increased by about twice the global average.[3]

-

Scientists have found a direct link between anthropogenic warming and the observed trend of increasing heat extremes over the western US.[4]

-

A warmer world has drier fuels, and drier fuels make it easier for fires to start and spread.

- Climate change has lengthened the window of time each year with weather that is conducive to forest fires.[1]

-

From 1979 to 2015, climate change accounts for 55 percent of observed increases in land surface dryness in western forests.[1]

-

From 2000 to 2015, climate change enlarged the area of forested land experiencing high fire-season aridity by 75 percent.[1]

-

Since 1984, climate change has doubled the cumulative area in the western United States that would have otherwise burned due to natural climate forcing alone.[1]

-

From 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the West.[5]

- More than half of states in the Western US have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[6]

Background information

The influence, or fingerprint, of climate change is easier to identify in some trends than others. In the case of wildfires, it's often challenging for scientists to parse out the influence of climate change versus other natural and human factors. This is because wildfires are heavily influenced by human land-use and management practices in addition to the weather and climate.[7]

Still, regardless of changes in the landscape due to forest management or what produces the initial sparks, hotter and dryer conditions due to human-caused climate change can make it easier for fires to spread. Observations show that climate change has already had a hand in shaping fire seasons, especially in California and the western United States. Below are some of the major climate-related factors at play.

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signal #1: Extreme heat

On a hot summer day, a small spark can ignite a raging wildfire. Due to climate change, extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent. Since 1970, average annual temperatures in the western United States have increased by 1.9°F, about twice the pace of the global average warming.[3]

The fingerprint, or influence, of anthropogenic warming in the observed trend of increasing heat extremes over the western US has been formally identified.[4]

There is a link between a warmer, drier climate and wildfires.

- Jennifer Balch, fire ecologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder[8]

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that forests burn when it's warm and dry, and we've seen more of those years recently.

- John Abatzoglou, climate and wildfire expert at the University of Idaho[8]

As the West heats up, conditions are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[3] During the period 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West, and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[5][9]

Heat in connection with 2018's wildfires

- May 2018: An unusually early extreme heat wave brought record temperatures to the Southwest. A month later, a series of fast spreading wildfires emerged.[10][11]

- June - July 2018: At the end of June and in early July, several major wildfires spread quickly in Colorado and northern California amid hot and dry conditions. The Spring Creek Fire in Costilla County, Colorado, is the third largest fire on record in the state at 108,045 acres burned.[12] The 416 Fire near Durango, Colorado, burned 54,129 acres and is the sixth largest fire on record.[12][13] In California, the Pawnee Fire in Lake County burned 15,185 acres, and the County Fire burned 90,288 acres. Hot and windy conditions helped the County Fire spread fast and contributed to growth in the Pawnee Fire in Lake County.[14] The temperature in Guinda, where the County Fire started, hovered around 104°F Saturday afternoon when the fire began.[14]

- July 2018: In late July, the Carr Fire in Shasta and Redding California exploded to 28,800 acres (45 square miles) “taking down everything in its path."[15] The fire began late on July 23 and tripled in size overnight on July 26 and 27 amid scorching temperatures, low humidity and windy conditions.[15]

- July 2018: California temperatures were as much as 10°F higher than normal in the months leading up to the Mendocino Complex fires,[16] and the state set a new record for both hottest July and hottest month with an average temperature of 79.7°F.

- May-October 2018: California experienced one of the hottest and driest 6-month-periods on record for the state.

- September-November 2018: Fall temperatures in California have risen about 3°F since 1980, setting the stage for wildfires like the Camp, Hill and Woolsey fires to break out late in the year. It was extraordinarily warm in Northern California over the two months leading up to the fires, particularly in the regions where they burned out of control.

Climate signal #2: Land surface drying increase

The amount of water in the air can be measured in terms of pressure; the more water there is in the air, the greater the pressure it exerts at the surface. Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) measures how much water is in the air versus the maximum amount of water vapor that can exist in that air, what's known as the saturation vapor pressure (SVP). As air warms, its capacity to hold water increases. Thus, its SVP increases as well. The greater the difference between the air’s actual water vapor pressure and its saturation vapor pressure, the more potential it will have to suck moisture from the ground.

VPD is used to measure dryness, or aridity, near the Earth's surface. It is directly related to the rate at which water is transferred from the land surface to the atmosphere. For example, as VPD increases—which means the air is less saturated with water—plants need to draw more water from their roots, which can cause the plants to dry out and die.

Observations show a direct link between climate change, vapor pressure deficits, and increased wildfire risk in the western United States. Between 2000–2015, human-caused temperature increase and vapor pressure deficit contributed to 75 percent more forested area in western US forests experiencing high fire-season fuel aridity. During this same period, high temperatures and VPD also added nine additional days per year of high fire potential.[1] In 2015-2016, human influences quintupled the risk of extreme vapor pressure deficits for western North America.[17] Looking further back in time, human-caused climate change accounts for 55 percent of observed increases in fuel aridity from 1979-2015 across western forests.[1]

Since 1984, climate change has doubled the cumulative area in the western United States that would have otherwise burned due to natural climate forcing alone.[1]

Drought and dryness in connection with 2018's wildfires

-

December 2017 - February 2018: California experienced its second-driest meteorological winter on record. Winter is normally the period during which the state receives most of its annual precipitation.[18]

December 2017 - February 2018: California experienced its second-driest meteorological winter on record. Winter is normally the period during which the state receives most of its annual precipitation.[18] -

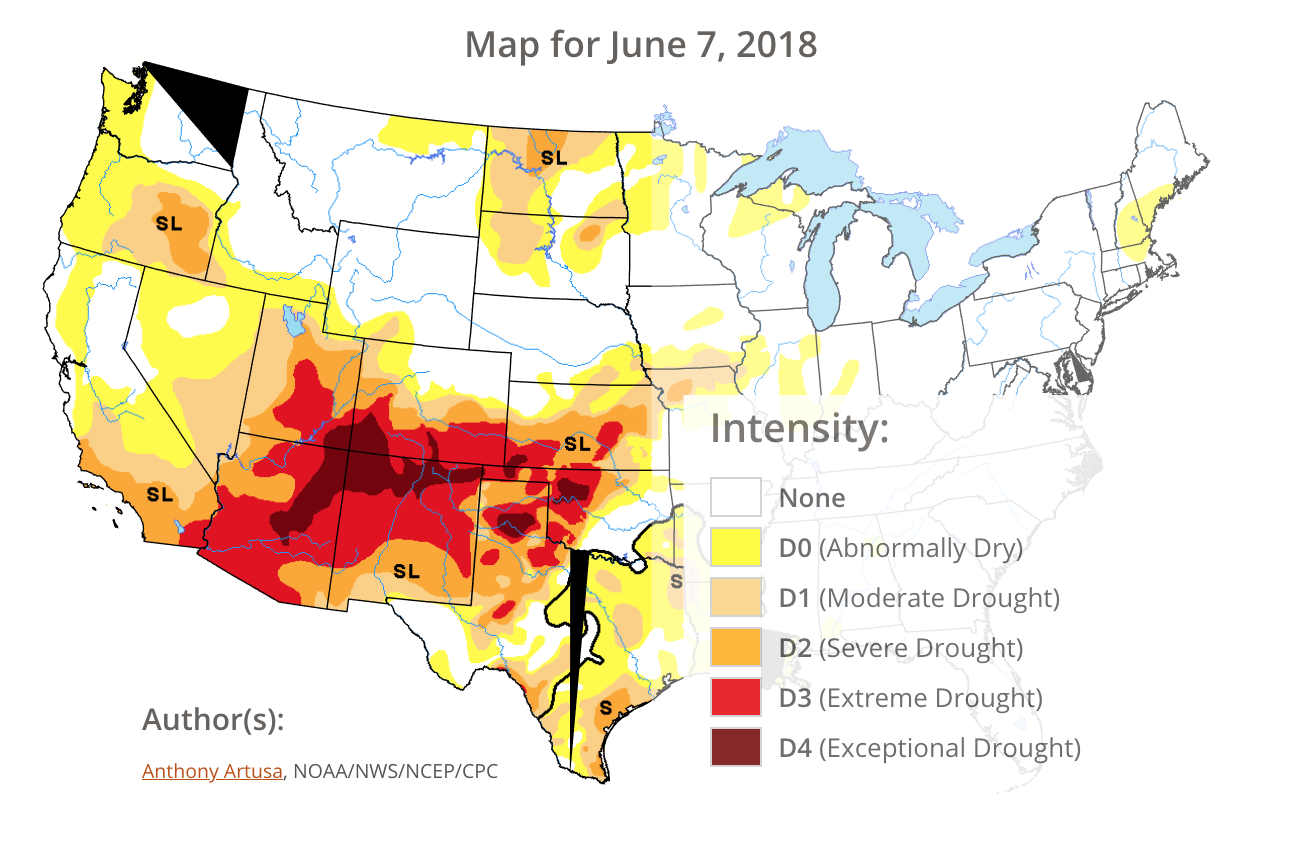

March 2018: The Southern High Plains were exceptionally dry during the winter of 2017-2018, which drove extreme drought conditions leading up to the Rhea Fire. The average temperature in Oklahoma during March was 3.6°F above the 20th century average.[19] The western third of Oklahoma had seen little more than 2 inches of precipitation since October—only about 20 percent of average—and most of the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles had received much less than 1 inch, making it the driest six months on record in some locations.[20]

-

June 2018: Much of the southwestern US experienced extreme and exceptional drought conditions after months of warmer than average temperatures and extreme heat in May.[21] Major wildfires burned in Colorado, causing officials to close San Juan National Forest's 1.8 million acres to the public for the first time in 100 years.[10] Wildfires also burned in New Mexico, Arizona, California, Utah, and Texas, according to the Forest Service.[10][11]

Our poor outdoor recreation economy has been suffering with no snow, no water, and now this. Closing the forest is just unprecedented.

- Kristin Carpenter-Ogden, founder of Verde Brand Communications, which has an office in Durango[10]

- July 2018: Vegetation moisture in many areas in northern California were at or near-record low levels at the end of the month.[22] Months of above-average temperatures left the northern Sacramento Valley bone-dry and ready to explode—facilitating the Carr Fire's spread.[23]

- June-August 2018: The fuels in northern California during the summer of 2018 were explosively dry due to a combination of low precipitation the previous winter, extremely high temperatures during the summer and the legacy of the long-term drought.[24]

- September-November 2018: There is an autumn drying trend in California, meaning fall rains that would normally reduce wildfire risk are becoming more erratic.[25] Autumn rainfall has decreased about one-third since 1980, priming the state for late-season wildfires like the Camp, Hill and Woolsey fires.

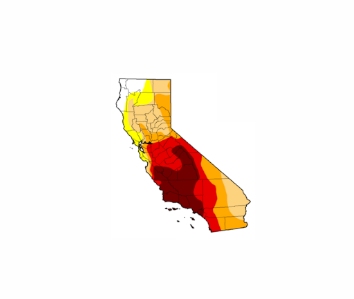

- November 2018: On November 6, 2018—just before the Camp, Hill and Woolsey fires broke out—the entire state of California was classified as abnormally dry. Half of the state was in moderate drought, and nearly 20% was in severe drought. The dry condition of the landscape in the lead-up to the fires was so record-breaking it had “no analog/comparison.”

- 2000-present: A period of long-term drought in the western US going back to 2000 has been attributed to global warming through the rise of temperatures.[26] It's also consistent with the projected long-term decrease in precipitation.[27][28][29] The longer-term drought also affects trees and dead fuel.

Climate signal #3: Longer fire season

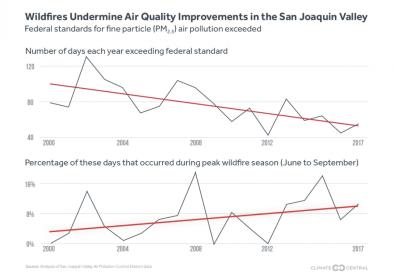

Climate change has lengthened the annual fire season (i.e., the window of time each year with weather that is conducive to forest fires).[1]

As the Earth warms, temperatures during the spring and fall are increasing in the western US. Snowpack, which is critical to water supply during the hot and dry summer season, is melting earlier and faster in the spring, and warmer temperatures are lasting longer into the fall. The result is a longer wildfire season and conditions that are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[3]

From 1980 to 2010, the length of the fire season expanded by 2.5 months.[5] During the period 2000-2015, climate change accounts for nine additional days per year of high fire potential.[1]

The length of the fire season is increasing in the Mountain West.

- Matthew Hurteau, associate professor at the University of New Mexico studying climate impacts on forests[30]

A lengthening fire season in connection with 2018's wildfires

Climate signal #4: Atmospheric blocking increase

"Blocks" in meteorology are large-scale patterns in the atmosphere that are nearly stationary, effectively "blocking" westerly winds and the normal eastward progression of weather systems. Blocking events in the western US are causing unusually prolonged hot and dry periods.

There is evidence suggesting that this pattern of prolonged heat and dryness in the West is linked to climate change.

Related Content