Media Briefing Report: Warming Temperatures and California Snowpack

Introduction

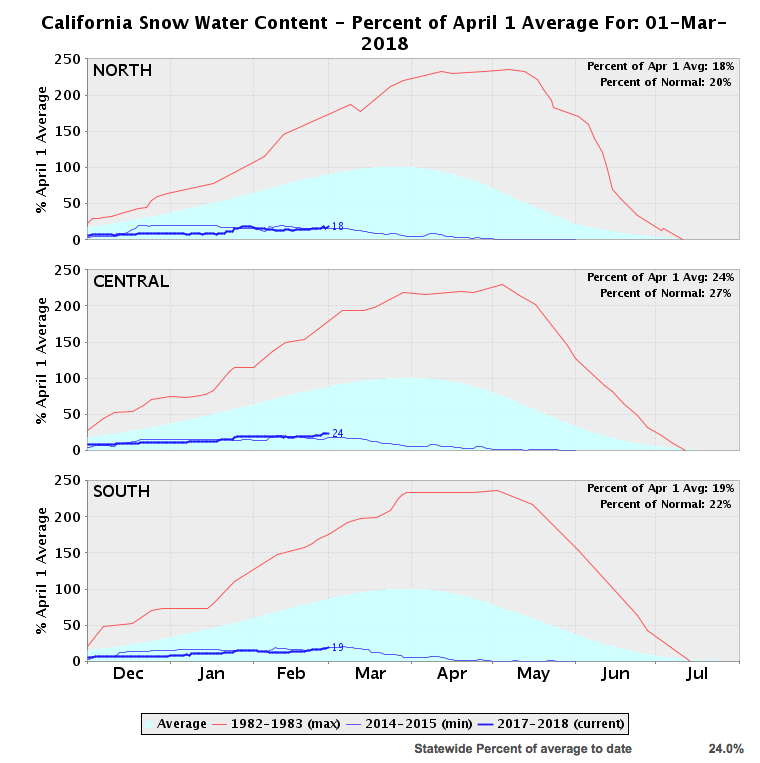

While the biggest snowfall of the season this coming weekend should boost snowpack totals in the Sierra Nevada, the long-term outlook remains grim. After months of snow drought, snowpack totals will still sit well below average and the end of the season looms.

Snowpack hand measurements as of March 1 show the snowpack sits at 24 percent of average. Near record-warm temperatures have been a driving factor in this year’s snow drought, causing a greater proportion of overall precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow. Average temperatures in the Sierras over the last 60 days ran 6-8 degrees F above normal over much of the mountain range. Likewise, overnight low temperatures, a key threshold for maintaining snowpack, ran 4-8 degrees F above normal.

Climate Nexus hosted a press call with panelists discussing the current snow drought, the potential for this storm to bring the state out of drought, and snow drought impacts on water and food supplies. The briefing was held in advance of closely watched March snowpack measurements that were pushed back by the snowstorm to Monday, March 5.

Highlights from the discussion are featured below.

Click here to access the full transcript, following the download link at the bottom of the page. The audio is available here. For science reports and more on the trends discussed in this briefing, click here.

Speakers

- Daniel Swain, NatureNet Postdoctoral Fellow at UCLA, expert on global warming and climate extremes

- Ellen Hanak, Director and Senior Fellow of the PPIC Water Policy Center, expert on water policy

- Renata Brillinger, Executive Director of CalCAN, expert on agriculture

Selected quotes

Daniel Swain

NatureNet Postdoctoral Fellow at UCLA, expert on global warming and climate extremes

There has been, already, a strong warming trend in the Sierra Nevada in recent decades, and that has resulted in a pretty substantial increase in the fraction of precipitation falling as rain rather than snow, and also an increase in the mean elevation in which that rain-snow line is occurring. And that regional warming trend is partially the product of greenhouse gases emissions, so it can be traced to human activities."

And snow losses are expected to accelerate in the future as that warming trend continues. And the final point relates to what's going on right now this week. Snowpack as of this morning, as was mentioned, is in the low 20's percent of average, which is actually still at a record, or very close to the record-low level. So I would estimate right now that this year, even after this big, multi-foot snow event coming up, we'll probably still be in the top five of record-low snow years after this weekend."

In this past decade there's been a really sustained trend towards seeing the snowline creep up the mountain. There was a study that came out a few months ago pointing to the fact that the snow line near Tahoe, Lake Tahoe, for example, over the past 10 to 15 years has been rising up the mountain at a rate of almost 300 feet per year vertically. And that's a big deal, because cumulatively over 10 or 15 years, that's a substantial chunk of the mountainside.”

In the other kind of fire regime we have in California, in the dense, coniferous forest for example, in the Sierra Nevada, the response of wildfire to snow drought, and drought in general is a little more straightforward. If you have these large trees in the forest, and there's a low snow winter, which means there's a warmer spring, because that snow feedback isn't keeping things cool and moist through the spring, it means that by the time summer rolls around, there's very little moisture in the soil for the tree to take advantage of. What ends up happening is those trees, in the summer time, and in the early autumn when this fire risk peaks, are drastically dryer than they would be, and they're more flammable, and they're more drought stressed, and they tend to burn more easily and more intensely.”

Ellen Hanak

Director and Senior Fellow of the PPIC Water Policy Center, expert on water policy

What the changing climate is doing is basically heating things up, so it's reducing the share of free storage that we get in the winter in our snowpack, and it's also seeming, already, to be increasing the variability, and kind of increasing the peaks of the dry and of the wet, and that's something that climate models are projecting is going to be more and more in our future.”

That really means thinking about connecting our surface reservoir storage system with our groundwater basins, and getting more of the water that we save up for dry years into the ground so that we make more room in our reservoirs for floodwaters, and for the fact that we have less snow and more rain coming in.”

What is happening with these changes in the mix between snow and rain is that we're putting stress on that piece of the equation. And what will have to happen over time is, we're going to have to be adjusting how we make room for flood water, and where we can put it. One piece of that is competition with the space and reservoirs for saving water for use in the summer, and in next year, so what's called the conservation part of it.”

Another option is to find ways to release more of those flood waters downstream and make room in the flood plains. This is something that's kind of an exciting trend in looking at flood management, of thinking about how to allow flood waters in some years to spread more out on the land in places where that is safe to do.”

Renata Brillinger

Executive Director of CalCAN, expert on agriculture

One of my first questions I always ask them, especially in years like this, is, 'How's the water situation where you are?' It's integral, obviously, to the business of producing food and fiber. And those folks really understand intimately the challenges that we're going to be facing with climate change to their businesses and to their communities.”

There's surface water, and there's ground water, and both are affected by snow droughts, and by decreased annual precipitation. And different farms in different regions really have relied differently on those sources, some just one, some the other, and some both. When the state's water infrastructure surface water delivery declines, as it has in the five-year drought that just temporarily ended last year, producers basically have two options. Number one, they can let their fields fallow, go unplanted.”

Something that doesn't always get talked about is that as we see our storage resources declining, that puts pressure on our electrical resources, our hydroelectricity, at the same time as we're requiring more energy generation to deal with the increased heat and increased irrigation demands. Now, going into this year, as Daniel said, even if we get a whopping storm in the next few days, we're still going to be pretty far behind. We're very likely to be entering a dry year as our big water demands go up in the summer with irrigation and landscaping uses.”

Governor Brown has also said, famously remarked that conservation should be a way of life in California, and that's 100% true. What needs to follow that statement, though, is a consistent, reliable, attention paid to making that possible in all sectors.“