Anatomy of the flood: Hurricane in 'infancy' was fueled by warm, moist Gulf air

The flooding that has devastated Baton Rouge and the surrounding parishes was caused by a rare weather phenomenon that could become increasingly common, analysts say.

It was largely the product of extremely warm, moist air in the Gulf of Mexico colliding with a slow-moving storm system, which drenched a swath of Louisiana over a several-day stretch.

In a way, it resembled a hurricane, even if it didn't have a name or the battering winds usually associated with one, said Barry Keim, the state climatologist. "This is basically like a hurricane in its infancy," Keim said.

While there wasn't the dramatic build-up that comes with watching a named storm cross the Gulf and there was no one-off phenomenon like El Niño to point to as the perpetrator, the weather system caused havoc nonetheless.

In some areas the rainfall was enough to qualify as a 500-year or 1,000-year event, something that has only a 0.2 percent or 0.1 percent chance of happening in a given year.

Experts caution that it may be too early to directly link the storms with climate change. But rising temperatures and a warmer Gulf of Mexico could mean more moisture in the air and more weather systems like the one that ravaged the state.

...

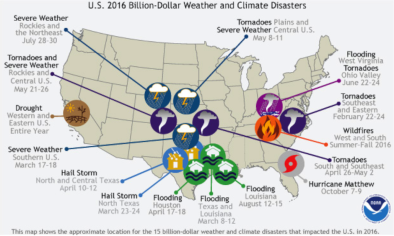

Heavy storms have become increasingly common across the country over the past half-century due to similar changes in conditions, said David Easterling, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Centers for Environmental Information.

"We've seen increases in water vapor over the past 35 or 40 years and seen an increase in the rainfall amounts since the middle of the 20th century," Easterling said. "It's completely consistent with what we expect to see with a warming climate."

Last week, a very large and slow-moving low-pressure system began drifting westward across the northern Gulf of Mexico, where the air was exceptionally saturated with moisture, Krautmann said.

Warm, wet air is not uncommon along the Gulf Coast in August, but last week it was primed for serious storms. The amount of moisture in the air was almost twice the amount that is typically seen in August, Krautmann said.

That meant there was an incredible potential for rain, which was unleashed when the system moved through.

"There was a huge amount of water vapor. A lot of that was coming off the Gulf -- a lot of evaporation, a lot of that is warm water -- and that feeds right into that very slow-moving storm that you guys had there," Easterling said. "The storm was unusual, a very slow-moving storm, and it had the ability to dump a heck of a lot of rain."

Because of circulation in the storm, it was able to keep drawing on the moisture from the Gulf, replenishing itself to dump more rain on the state, Keim said.

The totals are staggering. Watson saw about 31.4 inches of rain in three days, Livingston took on nearly 22 inches of water, and Baker recorded more than 21 inches

Related Content