High Plains Drought 2017

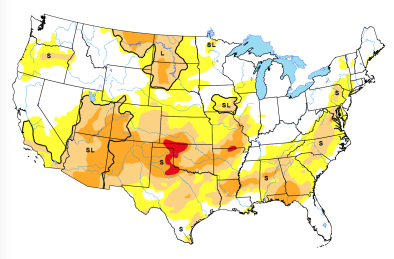

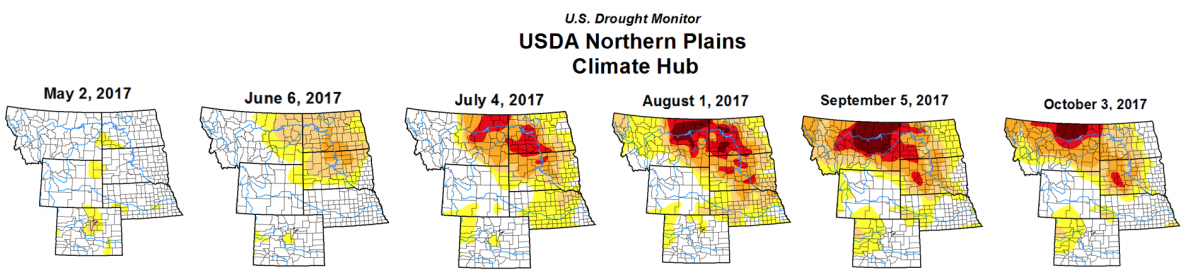

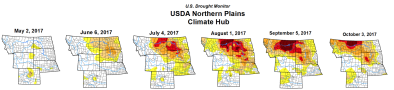

In early May, the U.S. Drought Monitor classified neither the Dakotas nor Montana in a drought. By July, and with the arrival of a major, slow-moving heat dome, all three states were experiencing large areas of severe to extreme drought. The drought had far reaching impacts, contributing to one of Montana's worst wildfire seasons on record and causing agricultural losses of $2.5 billion.[1]

Climate change amplifies the intensity, duration and frequency of extreme heat events that can exacerbate drought conditions. Climate change also increases wildfire risk by influencing the variables that start and fuel fires. Finally, the heat dome that rapidly intensified drought conditions in July also has links to climate change.[3]

Climate science at a glance

- A number of individual event attribution studies suggest that if a drought occurs, anthropogenic temperature increases can exacerbate soil moisture deficit.[1][2]

- Almost all of the high-intensity heat domes — like the one that settled over the western US in July — have occurred since 1983, with the overwhelming majority of them occurring since 1990.[3]

- From 1979 to 2015, climate change was responsible for more than half of the dryness of Western forests and the increased length of the fire season.[4]

- Recent decades have seen a profound increase in forest fire activity over the western United States.[5]

Low rain combined with abnormally warm temperatures fuel flash drought in the High Plains

Flash droughts refer to relatively short periods of low and rapidly decreasing soil moisture, driven by a lack of precipitation or warm temperatures.[6] The drought in the High Plains featured both.

The dry pattern began in the spring, with Glasgow, Montana, registering its driest April through June period on record.[7] The drought intensified further in July when a heat dome elevated temperatures and suppressed the formation of rain for weeks.[7] Temperatures in Montana, Wyoming and the Dakotas surged into the 90s and 100s, about 15 to 20°F above normal, causing dry conditions to expand quickly.[7]

July was one of the hottest and driest months on record for Billings and elsewhere in Eastern Montana.[8] In just one week, the area of Montana covered by the most extreme grade of drought (what the U.D. Drought Monitor calls "exceptional drought") jumped from 1.5 percent to 12 percent.[8] Exceptional drought conditions are generally considered a 1-in-100 year event, according to David Miskus, a research scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.[8]

South Dakota reached its peak on July 18 with 82 percent of the state classified in drought. North Dakota reached its peak on September 12 at 93 percent, and Montana reached its peak on September 5 at 91 percent.

Climate change linked to more extreme heat, more frequent heat domes, and increased wildfire risk

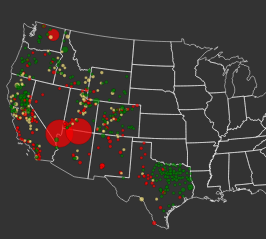

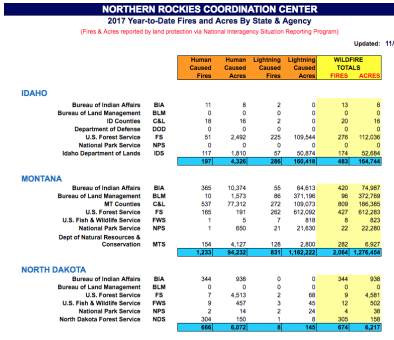

In 2017, Montana burned 1.28 million acres, making 2017 the state's second-worst wildfire season on record, due in part to the extreme heat and drought.[9] Governor Steve Bullock of Montana declared the wildfires a disaster on September 1, calling it “one of the worst fire seasons” in the state’s history.[10]

From 1979 to 2015, climate change was responsible for more than half of the dryness of Western forests, including Montana, and the increased length of the fire season.[4] Since 1984, those factors have enlarged the cumulative forest fire area by 16,000 square miles, about the size of Massachusetts and Connecticut combined.[4]

The heat dome that rapidly intensified drought conditions in July (see image to the right) also has links to climate change.

The heat dome that rapidly intensified drought conditions in July (see image to the right) also has links to climate change.

Looking through records back to 1958, Ryan Maue, a meteorologist at WeatherBell Analytics, found that almost all of the high-intensity heat domes — like the one that settled over the western US in July — have occurred since 1983, with the overwhelming majority of them occurring since 1990.[3]

Agricultural impacts of the flash drought

The drought caused extensive impacts to agriculture in North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana, estimated at $2.5 billion.[11] Field crops including wheat were severely damaged and the lack of feed for cattle forced ranchers to sell off livestock.[12]

The Dakotas and Montana recently surpassed Kansas as the most important wheat-growing region in the country as the climate warmed, shifting crop suitability.[12] The High Plains is now a supplier of staple grain for the entire world.[12] According to recent field surveys, more than half of this year’s harvest may already be lost.[12]

Related Content