Western Wildfire Season 2017

Climate change is increasing wildfire risk in the American West through higher temperatures, reduced snow pack, increased drought risk, and earlier onset of springtime.[1]

Record hot and unseasonal temperatures dominated the start of 2017's western wildfire season. Record heat in February fueled worsening drought conditions in the Great Plains, contributing to extreme fire conditions in early March that precipitated major blazes in Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Texas. One of the fires was Kansas's largest single blaze in recorded history, beating the previous record set in March 2016.

In June, the first of two major back to back heat waves settled over the Western US, drying out lighter vegetation that sprouted after an especially wet winter in states such as California. The second heat wave hit in early July, fueling many major blazes in several western states, including California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Montana, and North and South Dakota.

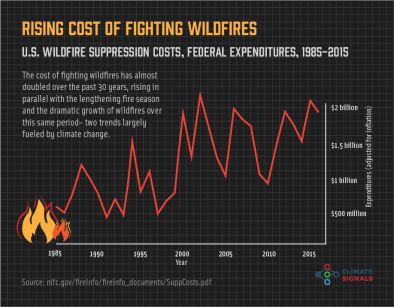

According to the US National Academy of Sciences, over the past 30 years, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West.[2] The length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[2][3] More than half of states in the Western US have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[3]

Climate science at a glance

- Higher temperatures, reduced snow pack, increased drought risk, and earlier onset of springtime are increasing wildfire activity in the western United States.

- Temperatures in the American West have gone up quickly. Since 1970, they have increased by about twice the global average.[1]

- Grassland fires have increased by more than 100,000 acres per decade since the 1970s, or 65 percent of annual average burned area.[2]

- In March, a massive grassland fire in Kansas linked to record heat and severe drought grew to 464,637 acres — the biggest single blaze in the state's recorded history. This beat the previous record set one year prior in March 2016. Back to back record events are a clear signal of climate change.

- Over the past 30 years, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West; the length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months; and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[3]

- More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.

Springtime western grassland fires tied to record February warmth

The US Department of Agriculture says wildfires from March and April 2017 in Kansas burned about 650,000 acres with the Starbuck fire—which burned 623,000 acres across Kansas and Oklahoma[4]—breaking the record for the biggest blaze on record in Kansas, at 464,637 acres.[5] (This beat the previous record set one year prior in March 2016.) Of Kansas’s 105 counties, 22 were affected by wildfires and estimated livestock losses are between 3,000 and 9,000 cattle.[5] About $36 million worth of fencing was also destroyed.[5]

In Oklahoma, the Northwest Oklahoma Complex, which includes 198,063 acres of the Starbuck Fire, burned nearly 400,000 acres and the livestock loss was estimated at 3,000 head of cattle.[5] Structure losses were estimated at $2 million with fencing losses at $22 million.[5]

Record hot temperatures in February 2017 swept across the US east of the Rockies and amplified drought conditions in the Great Plains, which helped to fuel record-breaking fires in March. Formal attribution work has identified the fingerprint of global warming in the record hot temperatures, as climate change increased the likelihood of such heat by threefold.[6]

A May 2016 study finds significant increases in wildfire activity in non-forest vegetation types, including shrub and grasslands like those in the Great Plains, within federal land management units.[2] Grass and shrubland fires have increased by 40,585 hectares (100,288 acres) per decade since the 1970s, or 65 percent of annual average burned area.[2]

Climate change linked to more extreme heat, more frequent heat domes, and increased wildfire risk

Extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent. Snow melts earlier in the spring. The result is a longer wildfire season and conditions that are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[1] Since 1970, temperatures in the American West have increased by about twice the global average, and the western wildfire season has grown from five to seven months on average.[1]

In late June and early July, back-to-back heat domes led to persistent, record breaking heat in the western United States.[7] A heat dome occurs when high pressure in the upper atmosphere acts as a lid, preventing hot air from escaping. The air is forced to sink back to the surface, warming even further on the way.

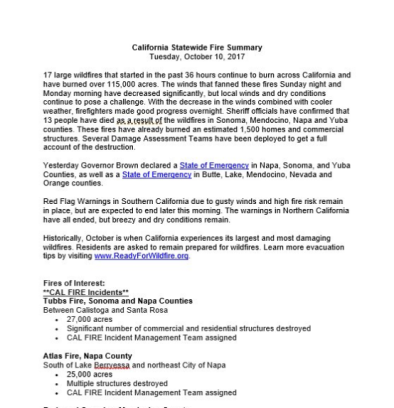

The heat dried out lighter vegetation that sprouted after an especially wet winter in states such as California. By July, the heat helped to fuel many major blazes in several western states, including California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Montana, and North and South Dakota.

In California, an explosive fire fed by “kindling-dry grass and trees” destroyed 41 homes and 57 structures near Oroville.[8] By mid-July, 586,800 acres had burned in Nevada making it the fifth-highest year in terms of total annual acres burned in the last 15 years, with a lot of time left. Nevada has also seen unusually large fires, with the Truckee Fire burning nearly 100,000 acres and the Rooster’s Comb Fire burning nearly 220,000 acres.

Looking through records back to 1958, Ryan Maue, a meteorologist at WeatherBell Analytics, found that almost all of the high-intensity heat domes — like the ones that settled over the Southwest in June and western US in July — have occurred since 1983, with the overwhelming majority of them occurring since 1990.[9]

Related Content