The Gulf of Mexico dead zone is larger than ever. Here’s what to do about it.

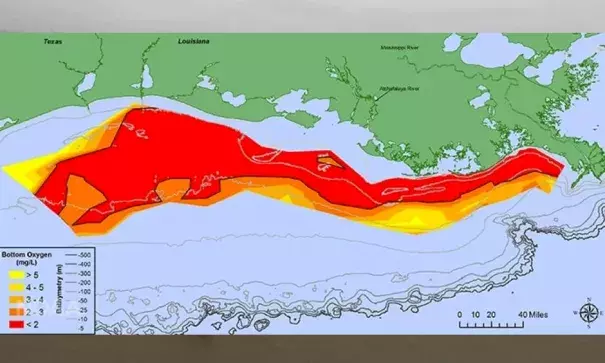

Dead zones occur throughout the world and persist through the summer until plunging water temperatures — and often hurricanes — mix oxygen back into the depths each fall. The hundreds of dead zones throughout the world cover nearly 100,000 square miles, with one in the Baltic Sea spanning more than 23,000 square miles several years ago. Collectively, nearly 10 million tons of biomass either moves from or dies in dead zones every year.

But these areas are preventable. Although oxygen depletion occurs naturally in some parts of the ocean, such as fjords and deep basins, the Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone is caused by humans. The nutrients these algal blooms feed on come from synthetic fertilizers and animal manure, human and industrial waste.

And though the oxygen loss is temporary, the effects can be permanent. “We have good evidence it is chronically affecting the reproduction of certain species,” said Robert Magnien, an algal bloom expert with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Models predicting what will happen if the dead zone persists show that species are likely to decline, added Alan Lewitus, who also studies nutrient pollution at the agency.

...

Matt Liebman, who studies cropping systems at Iowa State University, is hopeful that a shift in agricultural practices in the Midwest could make a big difference for the Gulf of Mexico. In a study published this year, his team showed that runoff could be reduced by 60 percent if farmers growing corn and soybean rotated in one or two more crops.

...

“I’m optimistic that we have a lot of technical answers,” he said, but “we need a market pull and a policy push.”

Such policy changes could include regulations, financial incentives for farmers to adopt conservation practices, and technical assistance to help farmers incorporate the changes. Yet even with a dramatic shift toward reducing runoff, Magnien warns that it could be 10 to 20 years before the gulf shows visible improvement.

Related Content