Rhea Fire 2018

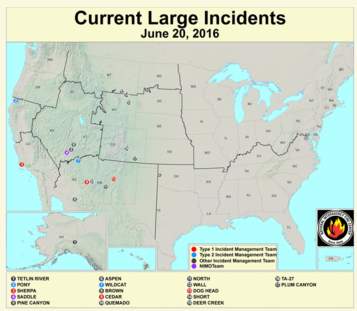

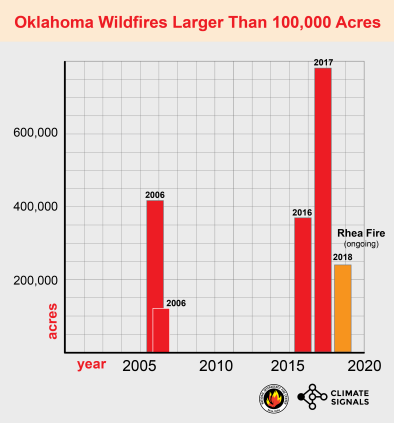

The Rhea Fire in Dewey County, Oklahoma—which burned 286,196 acres in total—is the third major fire in three back-to-back years to tear through hundreds of thousands of acres in the Oklahoma Plains. These fires are three of the five worst fires on record in Oklahoma, going back to 1997. Unusually hot temperatures contributed to the extreme fire conditions that fueled each of them.

These record-breaking wildfires are consistent with the long-term increasing wildfire activity observed in the western US grasslands, an increase fueled in part by climate change trends in the Great Plains region.

Climate science at a glance

- Three mega-fires have burned in Oklahoma over last three years.

- Unusually hot temperatures amplified the drought conditions that fueled the Rhea fire.

- Grass and shrubland fires have increased by 100,288 acres per decade since the 1970s, or 65 percent of annual average burned area.[1]

- Extreme events—and in particular, back-to-back-to back annual extreme events—are a classic signal of climate change.

Climate Signal #1: Wet summers followed by hot and dry winters increase fire risk

Each of the big three fires in 2016, 2017, and 2018 featured similarly conditions: unusually wet summers and falls followed by unusually hot and dry winters. According to state climatologist Gary McManus, November - December 2015 was the wettest on record; the summers of 2016 and 2017 were moist; and August 2017 was the state's second wettest on record.[2] The result is an unusually lush landscape that can transform into highly flammable wildfire fuel under dry and hot winter conditions, as was the case in 2016, 2017, and 2018.

Each of the big three fires in 2016, 2017, and 2018 featured similarly conditions: unusually wet summers and falls followed by unusually hot and dry winters. According to state climatologist Gary McManus, November - December 2015 was the wettest on record; the summers of 2016 and 2017 were moist; and August 2017 was the state's second wettest on record.[2] The result is an unusually lush landscape that can transform into highly flammable wildfire fuel under dry and hot winter conditions, as was the case in 2016, 2017, and 2018.

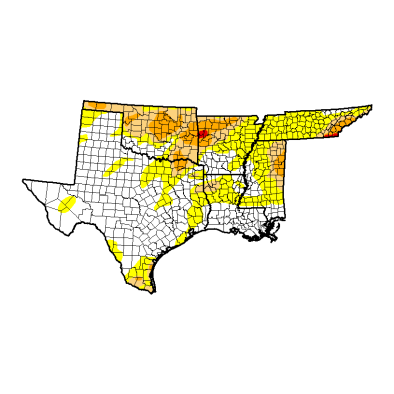

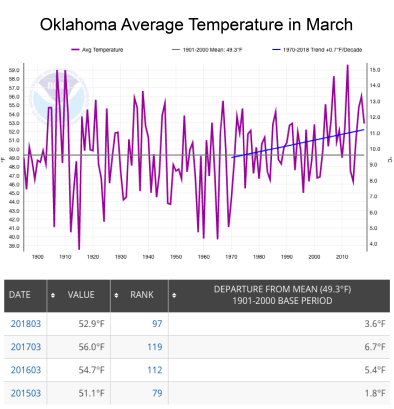

The Southern High Plains were exceptionally dry during the winter of 2017-2018, which led to extreme drought conditions heading into wildfire season. The average temperature in Oklahoma during March was 3.6°F above the 20th century average.[3] The western third of Oklahoma had seen little more than 2 inches of precipitation since October—only about 20 percent of average—and most of the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles had received much less than 1 inch, making it the driest six months on record in some locations.[2]

These conditions—a wet summer and fall followed by a hot and dry winter—contributed to the extreme fire risk in March and April 2018 that fueled the rapid growth of the Rhea Fire.

Formal science study has identified the fingerprint of global warming in the record hot temperatures that swept across the US east of the Rockies in February 2017, as climate change increased the likelihood of such heat by threefold.[4] That heatwave helped to prime the Great Plains Wildfires of March 2017, which included Oklahoma's largest wildfire on record.

Climate Signal #2: The frequency and intensity of wildfires in the Great Plains are increasing

The frequency and intensity of wildfires in the Great Plains are increasing as the combination of higher temperatures, untamed underbrush and more extreme drought elevate wildfire risk.[1]

Since the 1970s, large grass and shrubland fires have increased by more than 100,000 acres per decade.[1] A 2017 study found that the total area burned by large wildfires in the Great Plains rose 400% over a three-decade study period (1984-2014).[5] The study also found that the average number of large wildfires in the biome increased from 33 per year from 1985 to 1994 to 117 wildfires per year from 2005 to 2014.[5]

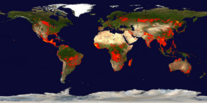

Worldwide, from 1979 to 2013, the length of fire season has increased nearly 19 percent.[6] In the US, the 10-year average number of acres burned in wildfires has more than doubled from the mid-1980s to 7 million acres now.[7]