Typhoon Soudelor 2015

Typhoon Soudelor made landfall on Taiwan’s east coast on Saturday, August 8th, 2015.[1] It was the latest of five cyclones this year to reach Category 5 status in the Western Pacific. Soudelor slammed the country at 5:00 am local time before making its final landfall in southeast China at 10:10 p.m Saturday.[1] Typhoon Soudelor’s eye had previously passed directly over the US territory of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands on Sunday, Aug 2nd and Monday, August 3rd.[1] It caused sufficient damage there to spur Acting Governor Ralph DLG Torres to declare a state of disaster and significant emergency.[1]

Climate change has been linked to more intense typhoon rainfall in the western Pacific.[3] A case study quantifying the effects of climate change on typhoon rainfall near Taiwan in the Northwest Pacific finds that modern-day typhoons yield more rainfall by about 5 percent.[4] Sea levels have risen eight inches globally as a result of warming, which in turn makes storm surges more destructive.[6] Global ocean warmth best explains the average increase in global tropical cyclone intensity, which one study quantifies at 1.3 meters per second over the past 30 years.[7] From 1981-2006, warming sea surface temperature (SST) trends are also correlated to increasing intensity of the strongest typhoons.[8] Human-caused increases in greenhouse gases have played a role in increasing SSTs across the Northwest Pacific typhoon formation regions throughout the 20th century.[9]

Soudelor’s Extreme Rain and Winds Worsened by Climate Change

Typhoon Soudelor made landfall on Taiwan’s east coast on Saturday, August 8th, 2015.[1] It was the latest of five cyclones this year to reach Category 5 status in the Western Pacific.

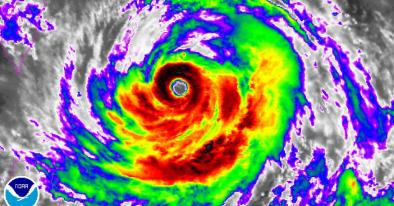

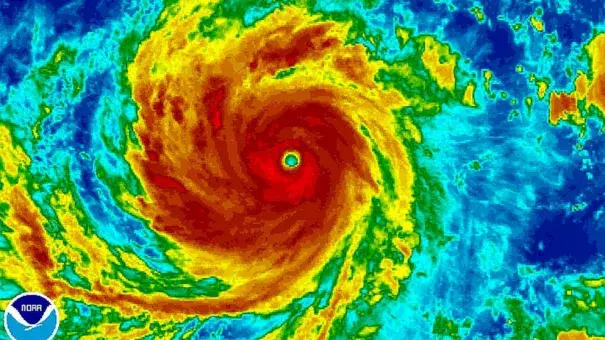

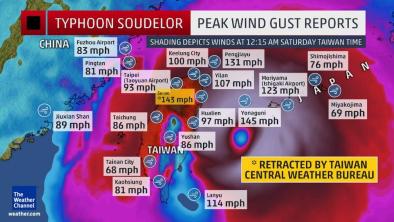

Soudelor slammed the country at 5:00 a.m. local time before making its final landfall in southeast China at 10:10 p.m Saturday.[1][1] On Thursday morning, the typhoon had sustained winds of 105 mph,[1] making it a strong Category 2 storm. It gained strength before hitting near Hualien, Taiwan, becoming a Category 3 with estimated top sustained winds of 120 mph.[1] In China's southeast, maximum sustained winds of 85 mph were recorded in Xiuyu District, Putian City in Fujian Province.[1]

Typhoon Soudelor’s eye had previously passed directly over the US territory of Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands on Sunday, Aug 2nd and Monday, August 3rd.[1] It caused sufficient damage there to spur Acting Gov. Ralph DLG Torres to declare a state of disaster and significant emergency.[1]

Magnifying concerns for Taiwan was the landslide threat from the combination of extreme rain and mountainous terrain. According to landslide expert Dave Petley, "The extreme rainfall totals generated by typhoons combined with the steep mountain front in eastern Taiwan means that the landslide potential for Typhoon Soudelor is very high."[2]

Typhoon rainfall is becoming more intense

Climate change has been linked to more intense typhoon rainfall in the western Pacific.[3] A case study quantifying the effects of climate change on typhoon rainfall near Taiwan in the Northwest Pacific finds that modern-day typhoons yield more rainfall by about 5 percent.[4] Warming air is projected to increase typhoon precipitation rates globally by another 20 percent before the end of the century, which is expected to lead to worse flooding worldwide.[5]

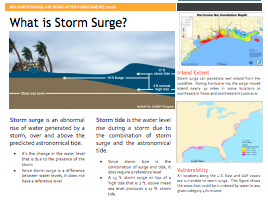

Sea level rise exacerbates storm surge during typhoons

Sea levels have risen eight inches globally as a result of warming,[6] which in turn makes storm surges more destructive.[7] During Typhoon Haiyan, which devastated the Philippines in 2013, storm surges were primarily responsible for the 6,300 dead, 1,061 missing and 28,689 people injured.[7]

Sea surface temperature positively correlated with intensity of strongest typhoons

Global ocean warmth best explains the average increase in global tropical cyclone intensity, which one study quantifies at 1.3ms-1 over the past 30 years.[8] From 1981-2006, warming SST trends are also correlated to increasing intensity of the strongest typhoons.[9] Human-caused increases in GHGs have played a role in increasing SSTs across the Northwest Pacific typhoon formation regions throughout the 20th century.[10]

Since 1984, the North Pacific has seen an increase in storm intensity, with a tendency for stronger but fewer storms.[11] Because damages are a function of wind speed, even slight increases in storm intensity lead to significant increases in damages.

Cyclone activity has shifted towards the coasts in east Asia in recent decades, resulting in storms of greater intensity making landfall over eastern China, Korea and Japan, according to a recent study.[12] Changing atmospheric circulation patterns resulting from a gradual warming of the western Pacific Ocean have shifted the areas where cyclones develop, moving them to the north and west.

Northwest Pacific trends

In 2015, accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) in the western North Pacific was extreme, and human-caused climate change "largely increas[ed] the odds of the occurrence of this event," according to the fifth edition of "Explaining Extreme Events from a Climate Perspective" by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.[13]

A number of studies have identified increasing trends in intense typhoon frequencies in the Northwest Pacific.[9][11][14][15][16]

A 2016 study documented the tight connection between increasing ocean warmth and the increasing intensity of typhoons in the western North Pacific, finding that "the energy needed for deep convection is on the rise with greater heat and moisture in the lower tropical troposphere," and that as a result, super typhoons in the region are, "likely to be stronger at the expense of overall tropical cyclone occurrences."[14]

However, other recent modeling work projects an increase in both the frequency and intensity of typhoons in the western North Pacific.[17]

Satellite-based intensity trends since 1981 show more modest trends.[18]

A study attempting to reconcile previous discrepancies among different sources of observations on typhoon intensity in the region identifies a trend of stronger, but fewer events.[11]

Related Content