Are more deadly mudslides inevitable? Experts say yes

Experts analyzing the catastrophic mudslide that claimed 20 lives here say there's no doubt it will happen again.

...

What caused the mudslide in this coastal town north of Los Angeles — home to Oprah Winfrey, Ellen DeGeneres, Rob Lowe and other celebrities — is no mystery.

After the Thomas Fire burned the mountainside above the developed area and changed the composition of its soil, a deluge occurred on the morning of Jan. 9. With vegetation burned away, there was nothing to hold hillsides in place, and a debris flow of mud, boulders and anything in its path roaring to the ocean.

What's been less discussed is the area's geology, which facilitated the debris flow.

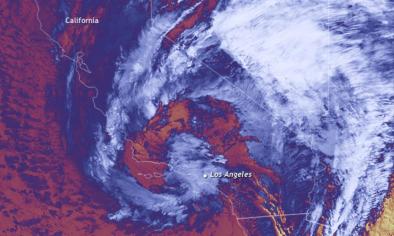

An alluvial fan is a cone-shaped layer of sediment crossed by many streams that is typically found where a canyon emerges onto a flatter plain. Jesse Allen/NASA

Called alluvial fans, the slopes were created over long periods of time as upland sediment erodes and slides to the valley floor or coastal area. This is often caused by an earthquake or wildfire followed by a fierce storm.

They're called fans because the sediment starts at a narrow point — the top of a mountain range, for example — then spreads as it travels into the shape of an upside-down fan or ice cream cone.

"Over geologic time, in mountainous areas in Santa Barbara County, Southern California and even around the world, alluvial fans are built by this process," said Jonathan Godt of the U.S. Geological Survey.

The geology is common in Southern California, particularly east of Los Angeles. And they are often prime tracts for developers, which can charge top dollar for elevated panoramic views.

"They are easily excavated, and we ... build on them," Godt said.

...

The good news is that after a debris flow, it's unlikely to happen again in the same place for a few hundred years, said Edward Keller, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

...

What makes debris flows so devastating, Keller said, is that unlike a fire — where crews can create defensive firebreaks to prevent the conflagration from leaping a highway — there's no stopping a debris flow.

"They flow as far as the energy allows," he said.

...

Keller said mandatory evacuation zones in advance of a debris flow should include its entire potential path. In the recent Montecito slide, the evacuation zone ended at a highway north of Montecito's southern-facing coast.

And he said more needs to be done to study the influence of climate change on precipitation patterns and wildfires, and whether that could make debris flows more frequent.

Related Content