Exclusive: Some Arctic Ground No Longer Freezing—Even in Winter

Nikita Zimov was teaching students to do ecological fieldwork in northern Siberia when he stumbled on a disturbing clue that the frozen land might be thawing far faster than expected.

Zimov, like his father, Sergey Zimov, has spent years running a research station that tracks climate change in the rapidly warming Russian Far East. So when students probed the ground and took soil samples amid the mossy hummocks and larch forests near his home, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, Nikita Zimov suspected something wasn't right.

In April he sent a team of workers out with heavy drills to be sure. They bored into the soil a few feet down and found thick, slushy mud. Zimov said that was impossible. Cherskiy, his community of 3,000 along the Kolyma River, is one of the coldest spots on Earth. Even in late spring, ground below the surface should be frozen solid.

Except this year, it wasn't.

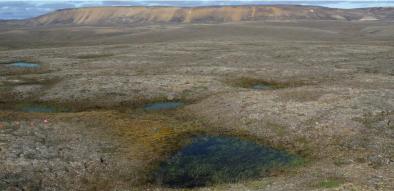

Every winter across the Arctic, the top few inches or feet of soil and rich plant matter freezes up before thawing again in summer. Beneath this active layer of ground extending hundreds of feet deeper sits continuously frozen earth called permafrost, which, in places, has stayed frozen for millennia.

But in a region where temperatures can dip to 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, the Zimovs say unusually high snowfall this year worked like a blanket, trapping excess heat in the ground. They found sections 30 inches deep—soils that typically freeze before Christmas—that had stayed damp and mushy all winter. For the first time in memory, ground that insulates deep Arctic permafrost simply did not freeze in winter.

...

The discovery has not been peer-reviewed or published and represents limited data from one spot in one year.

...

"This is a big deal," says Ted Schuur, a permafrost expert at Northern Arizona University. "In the permafrost world, this is a significant milestone in a disturbing trend—like carbon in the atmosphere reaching 400 parts per million."

Related Content