The polar vortex is about to split into 3 pieces: Here's what it means

Scientists are seeing signs that global weather patterns toward the latter half of January and into February may shift significantly to usher in severe winter weather for parts of the U.S. and Europe.

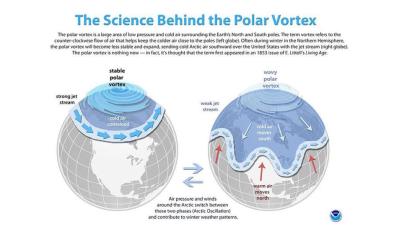

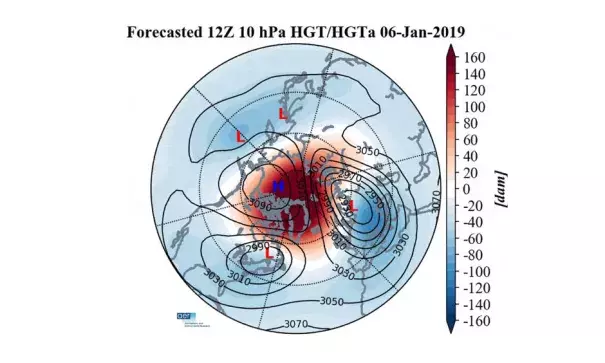

How it works: The possible changes are being triggered by a sudden and drastic warming of the air in the stratosphere, some 100,000 feet above the Arctic, and by a resulting disruption of the polar vortex — an area of low pressure at high altitudes near the pole that, when disrupted, can wobble like a spinning top and send cold air to the south. In this case, it could split into three pieces, and those pieces would determine who gets hit the hardest.

The big picture: Studies show that what happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic, and rapid Arctic warming may paradoxically be leading to more frequent cold weather outbreaks in Europe, Asia and North America, particularly later in the winter.

During the past 2 weeks, a sudden stratospheric warming event has taken place, showing up first in the Siberian Arctic, and then spreading over the North Pole.

Such events occur when large atmospheric waves surge beyond the troposphere and into the layer of air above it. Such a vertical transport of energy can rapidly warm the stratosphere, and set in motion a chain reaction that disrupts the stratospheric polar vortex.

Sudden stratospheric warming events are known to affect the weather in the U.S. and Europe on a time delay — typically on the order of a week to several weeks later, and their effects may persist for more than a month.

"In general, we see colder than normal temperatures over much of the U.S. and Europe/Northern Asia, and warmer than normal temperatures over Greenland and subtropical Africa/Asia" in the 60 days following sudden stratospheric warming events, Amy Butler, a research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, told Axios in an email.

Related Content