Blue Cut Fire 2016

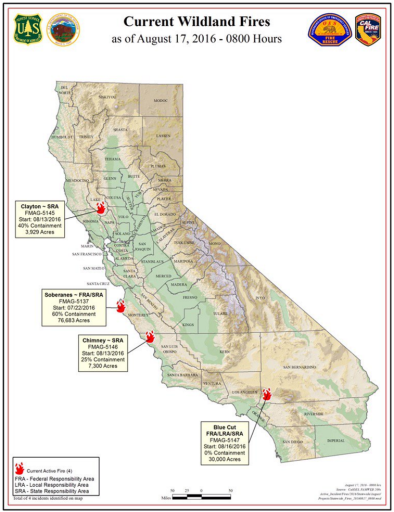

The Blue Cut Fire began in Cajon Pass in southern California as a small brush fire at 10:36am on August 16 and immediately escalated into a major blaze, consuming 18,000 acres in a matter of hours due to bone-dry hillsides, unusually high temperatures that peaked a 102°F, extremely low humidity, and gusty winds up to 45 mph. By early the next morning, the fire had consumed 30,000 acres.

Exactly one week after it ignited, fire officials declared the devastating wildfire fully contained, peaking at 37,020 burned acres. The fire destroyed an estimated 105 homes and 213 other structures in San Bernardino County and now ranks as the 20th most destructive wildfire in state history.

Extreme heat, years of ongoing drought, and tree die off—all fueled by climate change—are increasing wildfire risk in California.

Hot, dry, and windy conditions set the stage for the Blue Cut Fire's rapid spread

On August 16, conditions in Cajon Pass in southern California were primed for wildfires. Temperatures in Cajon Pass peaked at 102°F—7°F above the region's average daily maximum temperature during the month of August. Low humidity resulted in a below zero dew point, and winds ranged from 15 to 25 mph with gusts up to 45 mph.[1] Much of southern California has remained, after five years of continuous drought, in a state of "exceptional drought," the worst of five drought categories according to the US Drought Monitor.

The Blue Cut Fire erupted at 10:36am on August 16 and spread at a rates over 1,000 acres per hour, burning 18,000 acres by the end up the day. Early on August 17, the first had consumed 30,000 acres.[2] Exactly one week after the Blue Cut blaze erupted in the Cajon Pass, fire officials declared the fire fully contained, peaking at 37,020 burned acres.[3]

The fire destroyed an estimated 105 homes and 213 other structures in San Bernardino County and now ranks as the 20th most destructive wildfire in state history, said Daniel Berlant, a spokesman for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.[4]

[The fire] hit hard, it hit fast, it hit with an intensity that we haven’t seen before. – Mark Hartwig, San Bernardino County fire chief [5]

A combination of high winds, high temperatures and low humidity in California’s fifth year of drought made for prime wildfire conditions. – Bob Poole, spokesman for the United States Forest Service [5]

One of the things that we’re seeing is that the fires are burning in really an unprecedented fashion...It’s to the point where explosive fire growth is the new normal this year, and that’s a challenge for all of us to take on. – Glenn Barley, the San Bernardino unit chief of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) [5]

Drier conditions due to warmer temperatures and ongoing drought increase California’s wildfire risk

The southwestern United States has already begun a long-predicted shift into a decidedly drier climate.[6] Extreme heat and years of ongoing drought, both linked to climate change, are increasing wildfire risk in California by contributing to the frequency and severity of wildfires in recent decades.[6]

Study of southern California wildfires has found the weather conditions (e.g. unusually hot local temperatures) are the primary driver of the size of spring and summer fires in these landscapes.[7]

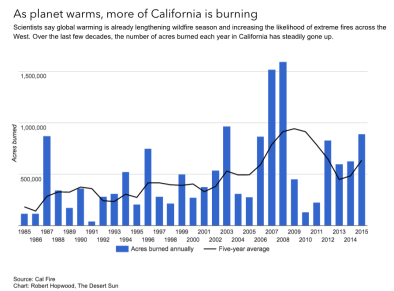

Observed changes in California's climate towards drier conditions and warmer temperatures help to explain why 14 of the states's 20 largest wildfires on record have all burned since 2000.[14][8]

Climate change has exacerbated naturally occurring droughts, and therefore fuel conditions.

- Robert Field, a research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies [9]

The fingerprint of climate change has been identified in California's wildfires

Extreme heat, years of ongoing drought, and tree die off—all fueled by climate change—are increasing wildfire risk in California. A formal modeling analysis has identified the fingerprint of global warming in California's wildfires, reporting that, "an increase in fire risk in California is attributable to human-induced climate change." [10]

Looking across the region: according to the US National Academy of Sciences, there has been a fourfold increase over the last 30 years in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West.[11] The length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[11][12] More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[12]

I don’t ever envision the fire season ever shutting down again. In areas like southern California, the deployment of staff and resources to deal with wildfire is going to become a permanent feature rather than a seasonal one. – Dr. Keith Gilless, Chair of CA State Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, Dean of UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources

Five years of continuous drought have weakened trees, rendering them susceptible to the bark beetle

Higher temperatures and drought have also weakened trees and increased their susceptibility to the bark beetle, resulting in tens of millions of dead trees across the state that have further fueled wildfires.

Higher temperatures and drought have also weakened trees and increased their susceptibility to the bark beetle, resulting in tens of millions of dead trees across the state that have further fueled wildfires.

The 2015 California Forest Health Highlights Report found that drought-stricken and fire-damaged trees fueled bark beetle outbreaks of epidemic proportions in areas of coastal and southern California, as well as throughout the central and southern Sierra Nevada range.[13]

The report states that western pine beetle activity has increased in the Angeles National Forest—where the Blue Cut Fire is located—and that tree mortality "has been persistent in this area for the past 3 years, impacting hundreds of acres of forested land. Ponderosa pine mortality also increased west of Crestline along Highway 138 on the San Bernardino National Forest." [13]

The report also finds that the polyphagous shot hole borer—an exotic beetle population—"have become fairly extensive in Los Angeles and Orange Counties." [13]

Related Content