Erskine Fire 2016

The fast-moving Erskine fire—one of many blazes in the southwestern US fed by extreme heat and dryness during the 2016 season—scorched 48,019 acres, destroyed 257 structures, and was responsible for two deaths. Kern County Chief Fire Marshall described the blaze as "One of the fastest moving, most destructive fires we've seen in state's history."

Extreme heat, years of ongoing drought, and tree die off—all linked to climate change—enabled the fire to spread quickly.

An array of climate signals in California are linked to fires like Erskine

The southwestern United States has already begun a long-predicted shift into a decidedly drier climate.[1] The shift has increased wildfire risk in California through higher temperatures, intensified drought, earlier spring snow melt, pine beetle infestations linked to warmer winter conditions, and tree die off.

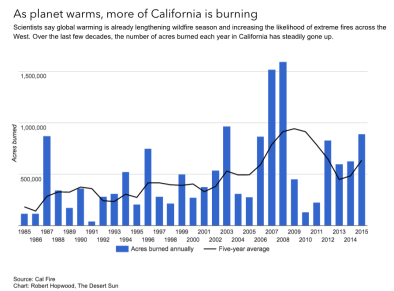

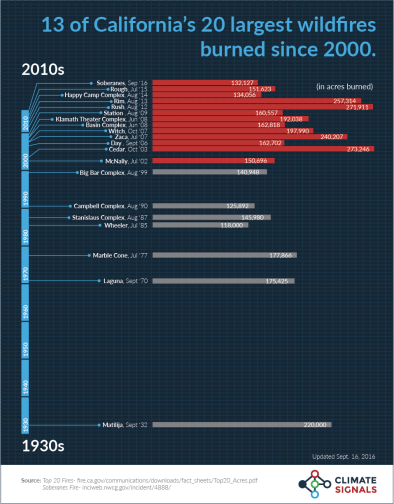

Fourteen of California's 20 largest wildfires on record have all burned since 2000,[2][3] while pine beetles, heat and California’s five-year drought have caused 66 million trees to die in the state’s Sierra Nevada forests since 2010.[4] A formal modeling analysis has identified the fingerprint of global warming in California's wildfires, reporting that "an increase in fire risk in California is attributable to human-induced climate change."[5]

The Erskine fire burned 48,019 acres, caused two deaths, and destroyed 257 structures.[6] The conditions that preceded and fueled the Erskine fire are consistent with California climate and wildfire trends. Extreme heat and dryness served as the perfect recipe for the Erskine wildfire,[7] according to NOAA, and officials reported that dead trees are playing a large role in the fire's power and volatility.[8]

Large wildfires in California are increasing alongside spring and summer temperatures

Large wildfires in California are increasing alongside spring and summer temperatures

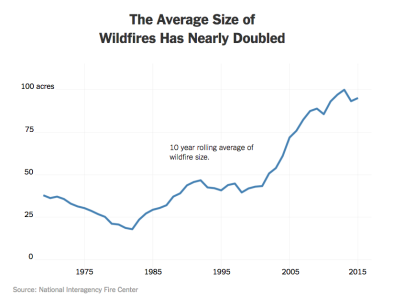

A June 2016 report by Climate Central finds that the average spring and summer temperatures in California have increased 1.8°F (1°C) since the 1970s.[9] Higher temperatures have been associated with increased frequency and severity of wildfire.

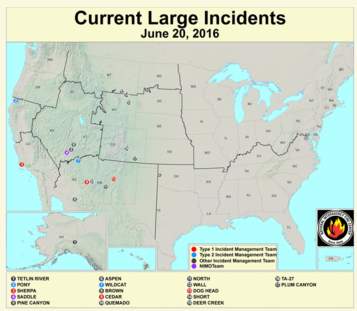

Global warming amplifies the threat of wildfires through increased heat and drought, reduced snow pack, season shift and pine beetle outbreaks

According to the US National Academy of Sciences, over the past 30 years, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West.[10] The length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[10][11] More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[11]

According to the US National Academy of Sciences, over the past 30 years, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West.[10] The length of the fire season has expanded by 2.5 months, and the size of wildfires has increased severalfold.[10][11] More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[11]

Higher temperatures, reduced snow pack, and earlier onset of springtime are leading to increases in wildfire in the western United States,[12] while extreme droughts are becoming more frequent.[13] Climate change is also affecting the prevalence and distribution of pine beetles, because warmer winter conditions allow the beetles to breed more frequently and successfully.[14][15]

Wildfires decreasing air quality and harming human health has been well-established

Exposure to smoke from wildfires increases the number of hospitalizations and medical visits associated with health issues like asthma, bronchitis, respiratory infections, and lung illnesses.[16][17]

In Nevada’s Reno/Sparks area alone, the 2008 fire season resulted in almost $2 million in hospital costs from wildfires within a 350-mile radius.[18]

Longer wildfire seasons and more costly fires are upending the US Forest Service budget

The United States spends roughly $2.0 to $2.5 billion on wildfire suppression per year, with suppression making up just a fraction of the total costs of a wildfire, which include damages to peoples' property, health and ecosystems and can be 10 to 50 times higher.[19]

The United States spends roughly $2.0 to $2.5 billion on wildfire suppression per year, with suppression making up just a fraction of the total costs of a wildfire, which include damages to peoples' property, health and ecosystems and can be 10 to 50 times higher.[19]

Over the last few decades, wildfire costs have increased as a percent of the Forest Service’s budget as fire seasons have grown longer and more costly.[20] In 2015, federal spending on suppression exceeded US$2 billion, just 15 years after first exceeding $1 billion.[21]

From 1995 to 2015, the amount of the Forest Service's budget used to manage wildfires—which includes preparedness, suppression, FLAME, and related programs—has more than tripled from 16 percent to 52 percent, reducing the National Forest System's 2015 appropriation by nearly $475 million, or 32 percent.[20]

The role of past fire management practices on wildfire trends varies by region

Past fire suppression has led to changes in fuels, fire frequency, and fire intensity in some southwestern ponderosa pine and Sierran forests but has had relatively little impact on fire activity in portions of the Rocky Mountains and in the low-lying grasses of southern California.[22]

Changes in firefighting practices over time—such as more frequent use of intentional burning to clear fuels as a fire suppression tactic—may have had impacts on the boundaries of burn areas, but generally, the effects of human development vary regionally, in some cases increasing fire activity and in others decreasing it.[22]

Western US trends for number of large fires in each ecoregion per year. The surrounding bar plots display the number of large fires in each ecoregion over the 1984–2011 study period.[23]

Western US trends for number of large fires in each ecoregion per year. The surrounding bar plots display the number of large fires in each ecoregion over the 1984–2011 study period.[23]

Related Content