Typhoon Haima 2016

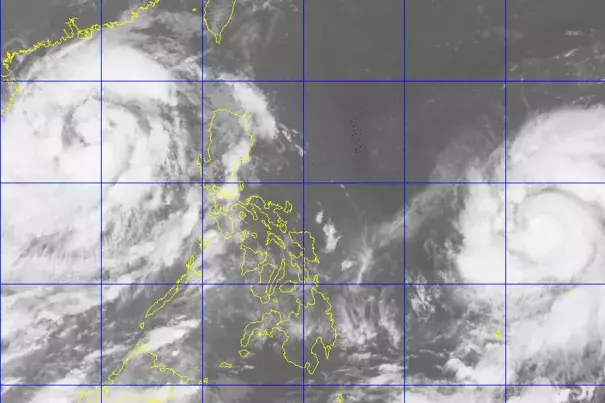

Super Typhoon Haima (known locally as Lawin) made landfall on the Philippines’ Luzon Island on October 19 as a Category 4 storm, just days after Typhoon Sarika (Karen) made landfall in central Luzon, also as a Category 4 storm. Sarika produced rainfall totals up to 20 inches, and Haima dumped another 10 to 20 inches of rain, with even higher local totals, across the northern half of Luzon.

As Haima approached the Philippines on October 18, the storm reached Super Typhoon, Category 5 status, packing maximum sustained wind speeds of 160 mph, and its hurricane-force winds extended more than 60 miles northeast of its center, making Haima a massive storm.

There is a documented increase in the intensity of the strongest storms in several ocean basins in recent decades, including the Pacific Northwest as well as a documented trend towards more rapid intensification. There is a significant risk that these increases are linked to warming seas that offer more energy to passing storms. Ocean warming increases evaporation driving extreme rainfall and the intensity of tropical weather systems. At the same time, a warmer atmosphere is able to hold and dump more water, a change that has already led to a significant increase in extreme precipitation and flooding risk. Along coastlines, sea level rise due to global warming increases the risk of coastal flooding by boosting the platform from which typhoons inundate coastal areas.

Climate science at a glance

- Sea level rise is increasing the reach of storm surge and flooding driven by hurricanes.

- Global warming loads hurricanes with more rainfall, increasing the threat of flooding.

- Tropical cyclones are growing stronger over recent decades. This trend is particularly strong in the Northwest Pacific Ocean.

- There is a significant risk that global warming is driving this trend.

Warming seas are increasing the limits for powerful storm

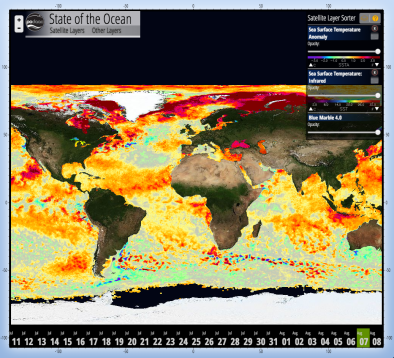

Tropical cyclones are fueled by available heat. During Typhoon Haima's intensification, sea surface temperatures were 1.7°F - 3.6°F above the average from 1985 to 2001, offering more energy to the storm.[1]

By increasing the potential energy available to passing storms, warming seas are effectively increasing the power ceiling or speed limit for these cyclones.[2] However, other factors, such as wind shear and the global pattern of regional sea surface temperatures, also play controlling roles. And the balance of these factors is not fully known.[3]

As seas warm and offer more heat energy, there has also been a global increase in the observed intensity of the strongest storms. The increase is well-documented and is consistent with models projecting the future climate, but scientists are still working to better understand the relation between these two trends.[2]

Typhoon Haima's rapid intensification consistent with observation that cyclones are intensifying faster

Beginning October 16th, tropical cyclone Haima rapidly intensified, over the course of just 24 hours, from a 85 mph storm to a Category 5 super typhoon with 160 mph winds.[4]

For a storm to be classified as "rapidly intensifying" its maximum sustained wind speeds must increase 35 mph (30 knots) in 24 hours, according to the National Hurricane Center's definition for rapid intensification.

The rapid intensification of Typhoon Haima is consistent with the observed trend indicating that tropical cyclones are intensifying faster.[5][6]

Tropical Cyclones are intensifying

There has been a global increase in the observed intensity of the strongest storms. The increase is well-documented and is consistent with models projecting the future climate in a warming world, but scientists are still working to better understand the relation between these two trends.[2]

A September 2016 study finds that the intensity of landfalling storms in the Pacific northwest is increasing.[7] Typhoons that strike East and Southeast Asia have intensified by 12 to 15 percent, with the proportion of storms of categories 4 and 5 having doubled or even tripled.[7]

Fewer but stronger storms would likely lead to an increase in overall damages

Damage incurred by tropical cyclones is overwhelmingly and disproportionately incurred by the most powerful storms, indicating that overall damage will increase as the climate warms.

Cyclone wind damage increases geometrically with an increase in speed.[8] A decrease in frequency would not be expected to offset the increase in damages incurred by increasing intensity. Moreover, damage escalates exponentially when storm strength crosses over the thresholds beyond which threatened infrastructure collapses.

It's the high end events that are the most destructive historically . . . More than half the damage that's been done in the United States by storms dating back to the middle of the 19th century has been done essentially by just eight events. So it really is the rare events, the Katrinas, the Sandys, that do the overwhelming amount of damage. Your average run-of-the-mill hurricane will do some damage and be memorable in the local place that if affects, but it doesn't really amount to a hill of beans compared to what the big storms do.

Dr. Kerry Emanuel [9]

More extreme rainfall

Climate change is also dramatically increasing the rainfall of tropical cyclones.[10] And an increase in rainfall rates is one of the more confident predictions of the effects of future climate change on tropical cyclones.[2]

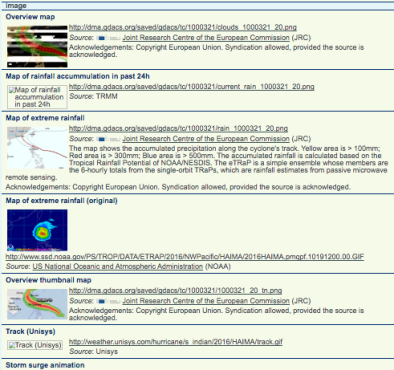

Haima dumped up to 14 inches of rain, with even higher local totals, across the northern half of Luzon, along a track roughly 100-150 miles north of Typhoon Sarika’s, which made landfall in Luzon during the early morning on October 16.[11][12] Baguio City (population 350,000) picked up over 14 inches of rain from Haima on October 20, and Tuguegarao City recorded 9.65 inches.[12]

Related Content