In Houston, Coronavirus Tests A City Known For Its Resilience

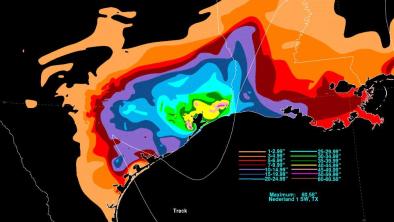

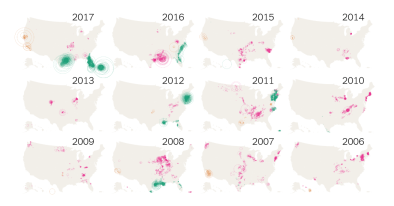

Climate Signals Summary: Climate change is increasing the amount of moisture the air can hold, and this increases the risk of extreme rainfall. Several attribution studies have found that climate change increased the amount of rain that fell during Hurricane Harvey.

Article Excerpt: In some ways, Drew Heyen thought he had grown numb to disasters. His family’s ranch-style home flooded nine times in 17 years, including two weeks before Hurricane Harvey and during the storm itself.

...

But he can’t prepare the same way for the new coronavirus, the largely invisible threat that Heyen is particularly vulnerable to. He’s almost 50 years old and diabetic, and in December, he got a respiratory infection that doctors believe caused his heart to fail.

...

In Kashmere Gardens, a historically black neighborhood in northeast Houston, Keith Downey has been trying to make sure 120 homebound seniors get meals. He’s still practicing social distancing because, as an asthmatic, he’s vulnerable to COVID-19. So he posts resources on social media and takes a lot of phone calls to help his community get through the pandemic.

“It’s like a freight train and you just can’t see the caboose, you know, because you don’t know how long this is going to last,” said Downey, president of the Kashmere Gardens super neighborhood.

During Harvey, the community got four-to-five feet of water. Downey said some residents are still dealing with mold and trying to rebuild. But now, he said, they’re also worried about getting sick from the virus — which some early data shows is disproportionately impacting African-American populations — and struggling to pay bills.

...

And in hurricanes, Houstonians are used to hunkering down and forecasting with familiar lingo about a wind event, or water event, or the “dirty side” of the storm.

But with the virus, Blanchard said it’s taken time for local leaders and residents to get up to speed on the “language and parameters of what this disaster means.”

“Like hurricanes, it’s a twin threat to our health and well-being and it’s a threat to our livelihoods,” Blanchard said. “We’re trying to form a shared understanding of what what we’re navigating.”

Related Content