Atmospheric Moisture Increase

A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture—about 7 percent more per 1.8°F (1°C) of warming—and scientists have already observed a significant increase in atmospheric moisture due to the air’s ability to hold more moisture as it warms. Storms supplied by climate change with increasing moisture are widely observed to produce heavier rain and snow. Research indicates that the increase in atmospheric moisture is primarily due to human-caused increases in greenhouse gases.

Read More

Climate science at a glance

- For each 1.8°F (1°C) of warming, saturated air contains 7 percent more water vapor on average.[1]

- The increase in atmospheric moisture content increases the risk of extreme precipitation events.

- Just as a bigger bucket can hold and dump more water, a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor and therefore dump more water when it rains.

- Atmospheric moisture has increased since 1976 and the increase is due primarily to human-caused climate change.[2][3]

Background information

Warmer air can hold more water

Warmer air holds more water because the water vapor molecules it contains are moving at a higher average speed than those in colder air making them less likely to condense back to liquid. According to the Clausius–Clapeyron equation, for each 1.8°F (1°C) of warming, saturated air contains 7 percent more water vapor, which may rain out if conditions are right.[1]

Atmospheric moisture content and ENSO

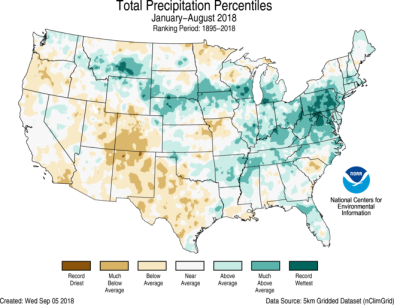

Increased atmospheric moisture content may also affect the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is a major driver of interannual climate variability, by intensifying regional precipitation variability, and associated extreme precipitation and drought events.

Global atmospheric moisture trends and climate change

- Surface air moisture content has increased since 1976, consistent with changes in atmospheric temperature and the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship, which states that the air holds about 7 percent more moisture per 1°C of warming.[2]

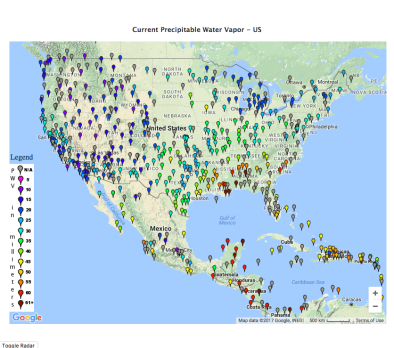

- Sea surface temperatures have risen by 0.5–0.6 °C since the 1950s, and over the oceans this has led to 4 percent more water vapor in the atmosphere since the 1970s.[4]

- The air is on average warmer and moister than it was prior to about 1970 and in turn has likely led to a 5 to 10 percent effect on precipitation and storms that is greatly amplified in extremes.[4]

- Observed moisture increases are largest in the tropics and in the extratropics during summer over both land and ocean.[2]

- The northern hemisphere is tending toward increasingly warmer and more humid summers, and the global area covered by extreme water vapor is increasing significantly.[5][6]

Water vapor has increased at rates consistent with Clausius-Clapeyron for the period 1987–2004 (1.3 percent per decades), and the relationship with changes in sea surface temperatures is sufficiently strong that it is possible to deduce an increase of about 4 percent in total column water vapor over the oceans since the 1970s.

Kevin Trenberth, a Distinguished Senior Scientist in the Climate Analysis Section at the National Center for Atmospheric Research [2]

Global studies attribute atmospheric moisture increases to climate change

- (IPCC, AR5): The fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC) states that humans have contributed to observed increases in atmospheric moisture content since 1960.[7]

- (Santer et al. 2007) model the response of atmospheric moisture to different external forcings and find, with high statistical confidence, that the large increase in water vapor over oceans is due primarily to human-caused greenhouse gas increases.[3]

- (Knutson and Ploshay, 2016): The fingerprint of climate change has been found in the increase of wet bulb temperature since 1973, driving heat stress globally and in most land regions analyzed.[8]

- Dr. Drew Fehsenfeld's research on joint health and climate change.