Wildfire Risk Increase

Climate change has increased wildfire risk through warmer temperatures and drier conditions that lengthen wildfire season, increase the chances of a fire starting, and help a burning fire spread. Warmer and drier conditions also contribute to the spread of the mountain pine beetle and other insects that can weaken or kill trees, building up the fuels in a forest.

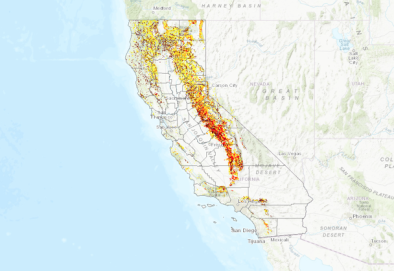

Scientists have observed a significant increasing trend in the number of large fires and the total area burned per year in the United States. In the West, anthropogenic climate change has been directly linked to drier conditions and increases in forest fire activity.[1][2][3][4]

Read More

Climate science at a glance

- Human-caused climate change is increasing wildfire activity across forested land in the western United States.

- The US National Climate Assessment reports that half of the increase in western wildfires is due to climate change.

- Higher temperatures, earlier snowmelt, drier conditions, increased fuel availability, and lengthening warm seasons—all linked to climate change—are increasing wildfire risk.

- A warmer world has drier fuels, and drier fuels make it easier for fires to start and spread.

- Climate change lengthens the window of time each year conducive to forest fires.

- Warmer winters have led to increased pest outbreaks and significant tree kills, with varying feedbacks on wildfire.

Background information

What factors influence the frequency of large wildfires?

The frequency of large wildfires is influenced by a complex combination of natural and human factors.[1] Temperature, soil moisture, relative humidity, wind speed, and vegetation (fuel density) are important aspects of the relationship between fire frequency and ecosystems.[1] Forest management and fire suppression practices can also alter this relationship from what it was in the preindustrial era.

How do fire management practices affect wildfire risk?

In addition to climate change, historic fire suppression has played a role in wildfire activity.

Past fire suppression has led to changes in fuels, fire frequency, and fire intensity in some southwestern ponderosa pine and Sierran forests but has had relatively little impact on fire activity in portions of the Rocky Mountains and in the low-lying grasses of southern California.[2]

Changes in firefighting practices over time—such as more frequent use of intentional burning to clear fuels as a fire suppression tactic—may have had impacts on the boundaries of burn areas, but generally, the effects of human development vary regionally, in some cases increasing fire activity and in others decreasing it.[2]

Regardless of changes in the landscape due to forest management, hotter and drier conditions due to human-caused climate change make it easier for fires to spread. Observations show that climate change has already had a hand in shaping fire seasons, especially in California and the western United States.

What is vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and how does it monitor surface dryness?

The amount of water in the air can be measured in terms of pressure; the more water there is in the air, the greater the pressure it exerts at the surface. Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) measures how much water is in the air versus the maximum amount of water vapor that can exist in that air, what's known as the saturation vapor pressure (SVP). As air warms, its capacity to hold water increases. Thus, its SVP increases as well. The greater the difference between the air’s actual water vapor pressure and its saturation vapor pressure, the more potential it will have to suck moisture from the ground.

VPD is used to measure dryness, or aridity, near the Earth's surface. It is directly related to the rate at which water is transferred from the land surface to the atmosphere. For example, as VPD increases—which means the air is less saturated with water—plants need to draw more water from their roots, which can cause the plants to dry out and die.

US wildfire trends and climate change

There is a link between a warmer, drier climate and wildfires.

- Jennifer Balch, fire ecologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder [3]

West

- Recent decades have seen a profound increase in forest fire activity over the western United States.[1]

- Hotter and drier weather and earlier snowmelt mean that wildfires in the West start earlier in the spring, last later into the fall, and burn more acreage.[4]

- Two climate factors affect fire in the western United States: increased fuel flammability driven by warmer, drier conditions and increased fuel availability driven by prior moisture.[5][6][7]

- There is a clear link between increased drought and increased fire risk.[7]

- More than half the US Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[8]

- From 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West; the length of the fire season expanded by 2.5 months; and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[8][9]

- Warmer winter temperatures affect the prevalence and distribution of pine beetles by allowing the beetles to breed more frequently and successfully.[10][11]

Climate change has exacerbated naturally occurring droughts, and therefore fuel conditions.

Robert Field, research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies[12]

Southwest

- The southwestern United States has already begun a long-predicted shift into a decidedly drier climate.[13]

- Higher temperatures, reduced snow pack, increased drought risk, and longer warm seasons are all linked to climate change, and in recent decades, these have increased wildfire risk, contributing to the frequency and severity of wildfires.[13]

- In California, 15 of the state's 20 largest wildfires on record have all burned since 2000.[14]

- In southern California, weather conditions, such as unusually hot local temperatures, are the primary driver of the size of spring and summer fires.[15]

Northwest

- A 2006 study found a statistically significant relationship between warming in the North Pacific and all the major wildfire events in the northwestern US from 1980-2002.[16]

Great Plains

- A 2017 study found that the total area burned by large wildfires in the Great Plains rose 400 percent over a three-decade study period (1984-2014).[17] The study also found that the average number of large wildfires in the biome increased from about 33 per year from 1985 to 1994 to about 117 wildfires per year from 2005 to 2014.[17]

Southeast

- The southeastern US (including Texas and Oklahoma) leads the nation in number of wildfires, averaging 45,000 fires per year,[4] and this number continues to increase.[18][19]

- Increasing temperatures contribute to increased fire frequency, intensity, and size.[4]

- Lightning is a frequent initiator of wildfires, and the Southeast currently has the greatest frequency of lightning strikes of any region of the country.[4] Increasing temperatures and changing atmospheric patterns may affect the number of lightning strikes in the Southeast, which could influence air quality, direct injury, and wildfires.[4]

Alaska

- Recent decades have seen a profound increase in forest fire activity in Alaska.[1]

- Total area burned and the number of large fires (those with area greater than 1,000 square km or 386 square miles) in Alaska have increased since 1959.[20]

US studies attribute increases in wildfire risk to climate change

-

(Partain et al. 2017) find that Alaskan fuel conditions during the 2015 fire season were 34 to 60 percent more likely to occur in today’s anthropogenically changed climate than in the past.[21]

(Partain et al. 2017) find that Alaskan fuel conditions during the 2015 fire season were 34 to 60 percent more likely to occur in today’s anthropogenically changed climate than in the past.[21] -

(Yoon et al. 2016) analyze the 2014 California wildfire season and identify an increase in fire risk in the state due to human-caused climate change.[22]

-

(Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016) look at the effects of human-caused temperature rise and air moisture decrease on wildfires across western US forests. They find that these human influences account for about 55 percent of observed increases in the dryness of wildfire fuels from 1979 to 2015. Human actions also contributed to 75 percent more forested area experiencing high fire-season fuel aridity and an average of 9 additional days per year of high fire potential from 2000 to 2015.[23] The authors estimate human-caused climate change contributed to an additional 16,400 square miles (the size of upper peninsula Michigan) of forest fire area from 1984 to 2015. This nearly doubles the area expected without global warming.[23]

Global wildfire trends and climate change

- A global analysis of daily fire weather trends from 1979 to 2013 shows that fire weather seasons have lengthened across 11.4 million square miles—about the size of Africa and 25.3 percent of the Earth’s vegetated surface—resulting in an 18.7 percent increase in global mean fire weather season length.[24]

Global studies attribute increases in wildfire risk to climate change

- (Jain et al. 2021): Extreme fire weather is being driven by a decrease in atmospheric humidity coupled with rising temperatures.

- (Tett et al. 2018) find that in 2015/2016, human-caused climate change quintupled the risk of extreme "vapor pressure deficits" (VPD) in western North America.[25] VPD measures how much water is in the air. Extreme VPDs indicate there is very little water in the air, which contributes to dryness, or aridity, at the Earth's surface and increased wildfire risk.