Ocean Acidification Increase

Ocean acidification—driven directly by rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere—is progressing steadily and measurably and is already taking a toll on sea life. Acidification is having a significant impact on the chemical composition of seawater, especially in colder basins like the Arctic where CO2 dissolves more readily. This change in ocean chemistry is threatening the healthy development of many marine species, and poses risks to humans who depend on oceans for their livelihoods.

Read More

Climate science at a glance

- One of the clearest outcomes from increasing carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere is the acidification of the world’s oceans.

- The oceans have taken up about 30 percent of the anthropogenic CO2 that has been released into the atmosphere since the start of the industrial era.

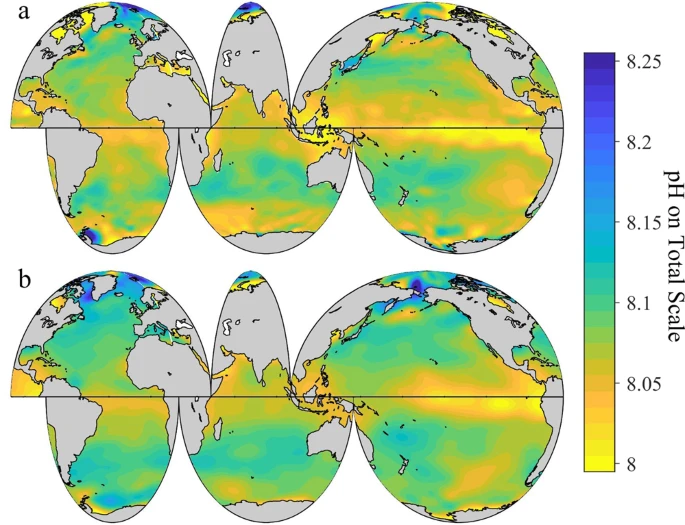

- From 1770 to 2000, the global average surface ocean pH decreased by about 0.11.

- Global pH in open ocean surface water has changed by –0.017 to –0.027 pH units per decade since the late 1980s.[1]

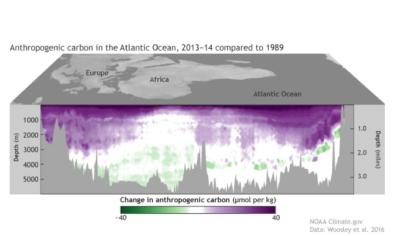

- Ocean acidification has occurred not only in the surface layer but also in the interior of the ocean.[2]

- The biodiversity and abundance of marine life, especially organisms that build calciferous shells and structures (e.g., coral reefs), have been reduced due to human-caused acidification.[2]

Background

What is ocean acidification?

The ocean’s chemistry is changing due to the uptake of human CO2 emissions. This process is commonly referred to as “ocean acidification”, and it is endangering coral reefs and the broader marine ecosystems.

The ocean’s chemistry is changing due to the uptake of human CO2 emissions. This process is commonly referred to as “ocean acidification”, and it is endangering coral reefs and the broader marine ecosystems.

Roughly 30 percent of the CO2 currently released by human activities is absorbed in the sea. While some of the CO2 is taken up by marine organisms, most if it combines with water to form carbonic acid. Ocean pH, carbonate ion concentrations ([CO32−]), and calcium carbonate mineral saturation states (Ω) have been declining as a result of the uptake.

How much ocean acidification has human greenhouse gas emissions caused?

Since the beginning of the industrial era, the pH of surface seawater has decreased from about 8.2 to 8.1. While the ocean is “basic” because it is above 7 on the pH scale, dissolved CO2 acidifies the ocean by increasing the concentration of hydrogen ion. The pH change from 8.2 to 8.1 corresponds to a 26 percent increase in acidity (or hydrogen ion concentration) and is likely the fastest acidification rate in 300 million years.[3]

How bad could ocean acidification get by the end of the century?

Without concerted action to reduce global CO2 emissions, oceanic pH could drop to 7.8 by the end of this century. That would be a huge change, representing a 150-percent increase in acidity. Such an alteration in the marine environment could have devastating results, for any marine species that extracts calcium carbonate to build its shell or skeleton, and for the people who depend upon them.

The ocean's buffer capacity could decrease by an average 34 percent from 2000 to 2100. This means that although the ocean will likely to continue to take up more CO2 in the future due to the ever increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration, the ocean’s role in absorbing human CO2 emissions will gradually diminish into the future, accelerating acidification.

Acidification won't stop immediately once humans reduce greenhouse gas emission. According to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, "[A]cidification [is] committed to ongoing change for millennia after global surface temperatures initially stabilize and are irreversible on human time scales." (IPCC, AR6, TS-71)

Global acidification trends

- (IPCC, AR6, 2021, TS-40): "[S]ea water pH has declined globally over the last 40 years, with human influence the main driver of the observed ocean acidification."[2]

- (IPCC, AR6, 2021, 1-22): "Ocean acidification is affecting marine life, especially organisms that build calciferous shells and structures (e.g., coral reefs). Together with less oxygen in upper ocean waters and increasingly widespread oxygen minimum zones and in addition to ocean warming, this poses adaptation challenges for coastal and marine ecosystems and their services, including seafood supply."

- (Gregor and Gruber 2021): The global mean trends for the period 1990 through 2018 for different measures of acidification are as follows: 8.6 ± 0.1 µmol kg−1 per decade for dissolved inorganic carbon, −0.016 ± 0.000 per decade for pH, 16.5 ± 0.1 µatm per decade for the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), and −0.07 ± 0.00 per decade for the calcium carbonate saturation state (Ω).

- (Bates and Johnson 2020): In the North Atlantic near Bermuda, ocean physics and chemistry has changed since the 1980s. There has been a recent acceleration of surface warming, salinification, deoxygenation, and changes in carbon dioxide (CO2)-carbonate chemistry that drives ocean acidification.

- (Gruber et al. 2019): The ocean is an important sink for anthropogenic CO2 and has absorbed roughly 30% of our emissions between the beginning of the industrial revolution and the mid-1990s.

- (Jiang et al. 2019): From 1770 to 2000, the global average surface ocean pH decreased by ~0.11 ± 0.03 units. Under the IPCC RCP8.5 “business-as-usual” scenario, the globally and annually-averaged surface ocean pHT would decrease by an additional ~0.33 ± 0.04 units (~114% increase in hydrogen ion) and the ocean’s buffer capacity would decrease by an average ~34% from 2000 to 2100.

- (Mollica et al. 2018): Ocean acidification directly and negatively affects the skeletal growth of Porites—a dominant reef-building coral. The skeletal density of Porites corals could decline by up to 20.3 percent over the 21st century solely due to ocean acidification.[4]

- (Perez et al., 2018): Acidification has been observed down to 3000 meters in the deep water formation regions.

- (Ríos et al., 2015): Acidification rates have been observed to be nearly as high in the intermediate waters of the North Atlantic as at the surface.