Why 2017’s tornado season is off to such an active start

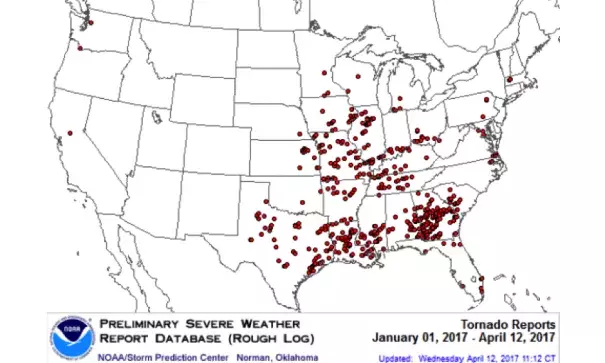

With hundreds of tornado reports only four months in, 2017 could rival both 2008 and 2011 as one of the most active tornado seasons in recent history.

However, as the United States' severe weather season shifts into its climatological peak, experts agree that it might be too early to determine.

“Certainly, we're off to a really fast start, but we haven’t gotten to the big part of the season yet,” said Harold Brooks, senior research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Severe Storms Laboratory.

“Half of tornadoes typically happen in May and June, so if those months end up being below normal, the year won’t be much above normal at all,” he said.

Since January, the National Weather Service’s (NWS) Storm Prediction Center data shows more than 500 possible reports of tornadoes in the U.S.

Both 2008 and 2011 had record tornado numbers.

2008's more than 2,100 possible tornadoes is considered well above the 10-year average, according to the Storm Prediction Center.

Of those, approximately 36 were rated between EF3 and EF5 (wind gusts ranging from 136 mph to more than 200 mph) on the Enhanced Fujita Scale.

In 2011, the National Centers for Environmental Information’s (NCEI) State of the Climate Report confirmed more than 1,600 tornadoes with a death toll of 551.

...

Experts say one of the reasons behind this active year could be the record warmth in the Gulf of Mexico, particularly near the western Gulf and the Loop Current, which is a flow of warm water that travels through the Gulf and past the Florida Keys.

“This leads to a more humid air mass over the Gulf, which can then be transported northward by wind into the U.S.,” said Dr. Victor Gensini, associate professor of meteorology at the College of DuPage in Illinois.

A relatively warm winter with fewer cold fronts across the southern U.S. might also be the cause, according to Dr. John Allen, assistant professor of meteorology at Central Michigan University.

“[This allows] warm, moist conditions to build, so that any systems that do come in have access to greater instability,” Allen said.

Related Content