Great Plains Wildfires March 2017

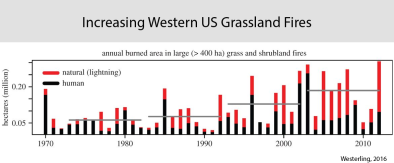

The record-breaking wildfires that erupted in early March in the Great Plains are consistent with the long-term increasing wildfire activity observed in the western US grasslands, activity driven by climate change trends in the Great Plains region.[1] Since the 1970s, large grass and shrubland fires have increased by more than 100,000 acres per decade. The frequency and intensity of wildfires in the Great Plains are increasing as the combination of higher temperatures, untamed underbrush and more extreme drought elevate wildfire risk.

Formal attribution work has identified the fingerprint of global warming in the record hot temperatures that swept across the US east of the Rockies in February 2017, as climate change increased the likelihood of such heat by threefold. The heat fueled worsening drought conditions in the Great Plains region, contributing to the extreme fire conditions in early March that precipitated major blazes in Kansas, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Texas.

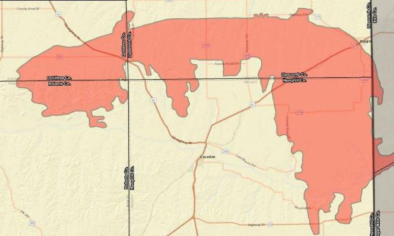

One blaze, encompassing Clark and Comanche counties along Kansas' southern border with Oklahoma, is the largest wildfire on record in the state. The previous record was set just one year prior.[2] Record-breaking events are a classic signal of climate change, as records tend to break when natural variation runs in the same direction as climate change, in this instance towards larger wildfires.

Climate science at a glance

- Drier conditions due to warmer temperatures and ongoing drought are increasing wildfire risk in the Great Plains.

- The fingerprint of global warming has been formally identified in the record hot temperatures that swept across the US east of the Rockies over the month prior to the fires.

- That record heat amplified the drought conditions that fueled record-breaking fires.

- Grass and shrubland fires have increased by 100,288 acres per decade since the 1970s, or 65 percent of annual average burned area.

- These record-breaking fires in 2017 follow the fires of 2016 that had set the prior record.

- Record breaking events and in particular back-to-back record-breaking events are a classic signal of climate change, as records tend to break when natural variation runs in the same direction as climate change,[1] in this instance towards large wildfires.

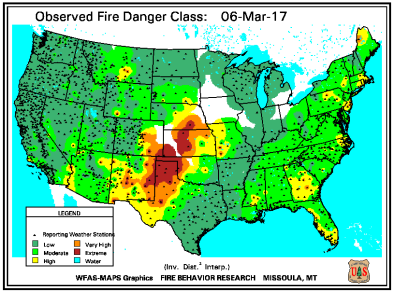

Record heat, drought and strong winds produced extreme fire conditions...

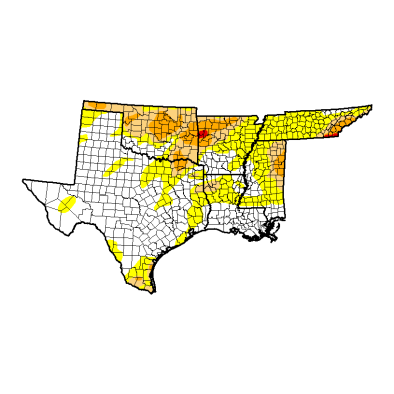

Drought conditions in the Great Plains—which were amplified by record warm temperatures in February[2]—combined with strong winds and low humidity to create extreme fire risk in the region entering the month of March.[3] All of eastern Colorado was classified as either moderately or abnormally dry in early March, along with much of Kansas and Oklahoma, and some of northern Texas.[4] Between February 7 and March 7, drought conditions around the Oklahoma panhandle worsened by one to two drought categories.[3][5]

Drought conditions in the Great Plains—which were amplified by record warm temperatures in February[2]—combined with strong winds and low humidity to create extreme fire risk in the region entering the month of March.[3] All of eastern Colorado was classified as either moderately or abnormally dry in early March, along with much of Kansas and Oklahoma, and some of northern Texas.[4] Between February 7 and March 7, drought conditions around the Oklahoma panhandle worsened by one to two drought categories.[3][5]

Noting the abundance of vegetation fuel, drought conditions and windiness in the southern central Plains, Liz Leitman, a Storm Prediction Center meteorologist, said Wednesday that "everything has come together to overlap to create a pretty volatile situation."[6]

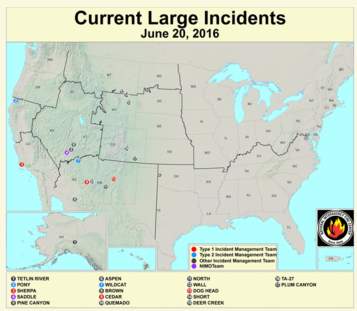

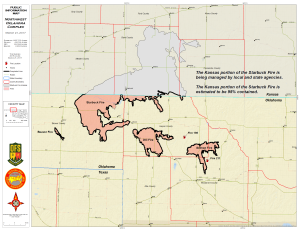

...that led to extreme, deadly and damaging fires

Beginning on March 4, a massive grass fire erupted in two Kansas counties, setting a state record by March 8 for the biggest single blaze in the state's recorded history.[7] As of March 8, the fire had burned an estimated 861 square miles (551,040 acres) of land in Clark and Comanche counties.[6] The 625 square miles (400,000 acres) burned in Clark County is about 85 percent of that county's total land area.[6] An estimated 659,070 acres (over 1,000 square miles) had burned across all affected counties in Kansas.[8]

In the Texas Panhandle, three fires burned about 750 square miles (480,000 acres), killing three ranch hands as they tried to save cattle and a man who was caught in smoke as he attempted to drive home from work.[9] The Perryton fire (the largest of the three fires) burned 497 square miles (318,156 acres) and was fully contained on March 12.

In Oklahoma, 200,000 to 300,000 acres had been charred in Beaver, Harper and Woodward counties as of March 7, leading Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin to declare a state of emergency in 22 counties.[10]

By March 26, the entire Northwest Oklahoma Complex fires, spanning the border between Oklahoma and Kansas, had burned 1,218 square miles (779,292 acres).

In northeastern Colorado near the Nebraska border, a fire has burned more than 45 square miles of land and destroyed three homes in Logan and Phillips counties.[10]

The fires have forced thousands to evacuate and have contributed to the deaths of at least six people.[10] The fires have also caused widespread destruction to cattle ranchers, particularly in Clark County, Kansas. Thousands of cows were killed, and with calving season approaching, lost cows could nearly double the number of animals lost.[11] On top of this, the cattle that does survive will have no grass or hay on which to feed, and many fences that lined the edges of the pasture—costing about $10,000 per mile—are gone.[11]

The fires have forced thousands to evacuate and have contributed to the deaths of at least six people.[10] The fires have also caused widespread destruction to cattle ranchers, particularly in Clark County, Kansas. Thousands of cows were killed, and with calving season approaching, lost cows could nearly double the number of animals lost.[11] On top of this, the cattle that does survive will have no grass or hay on which to feed, and many fences that lined the edges of the pasture—costing about $10,000 per mile—are gone.[11]

For daily state-based wildfire situation reports, click the following links: Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Colorado.

The Great Plains wildfires are consistent with climate change trends

Worldwide, from 1979 to 2013, the length of fire season has increased nearly 19 percent.[12] In the US, the 10-year average number of acres burned in wildfires has more than doubled from the mid-1980s to 7 million acres now.[13]

A May 2016 study finds significant increases in wildfire activity in non-forest vegetation types, including shrub and grasslands like those found in the Great Plains, within federal land management units.[14] Grass and shrubland fires have increased by 40,585 hectares (100,288 acres) per decade since the 1970s, or 65 percent of annual average burned area.[14]

Formal attribution work has identified the fingerprint of global warming in the record hot temperatures that swept across much of the US east of the Rockies in February 2017, as climate change increased the likelihood of such heat by threefold.[2]

Back-to-Back Record-Breaking Wildfire Years

Wildfires in Kansas have set records in two consecutive years, with the record for largest blaze set in March 2016 soon beaten in March 2017. Last year's setup shares many similarities to 2017: in both cases record and near-record temperatures blanketed the area.[15] In 2016, a NOAA analysis found that the fire was linked to very warm temperatures that made dry spells drier by pulling more water out of the soil through evaporation and plant transpiration.[15]

In 2013, University of Illinois atmospheric sciences professor Don Wuebbles warned that the frequency and intensity of wildfires likely would increase in the coming years, given the confluence of such factors as higher temperatures, untamed underbrush and worsening drought conditions, saying, "this probably is the new normal."[10]

Related Content