Marine heatwaves exacerbate climate change impacts for fisheries in the northeast Pacific

Study key findings & significance

Related Content

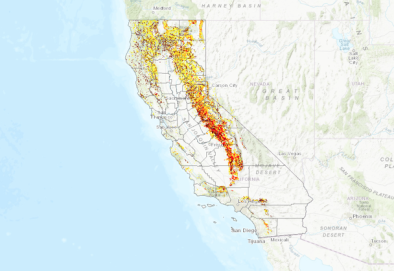

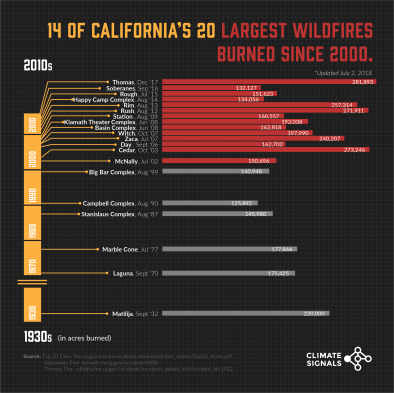

UPDATED Aug 2021: California's 20 Largest Wildfires

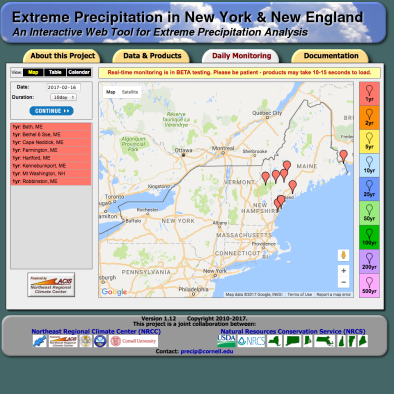

Eastern US Arctic Invasion and Winter Storm January 2018

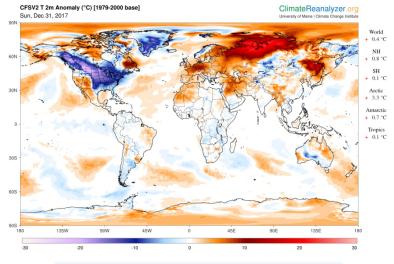

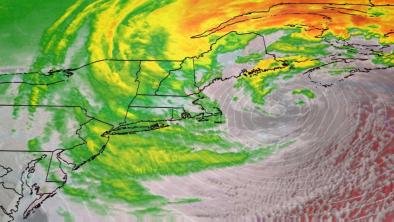

The intense cold hitting the United States during the first week of 2018 continued with a heavy snowstorm that inundated the Northeast seaboard beginning the night of January 3 through January 4. The combined impact of the arctic outbreak and the intensified nor’easter landed a double whammy in which new record low temperature records were set.

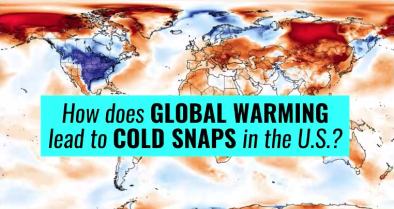

Science studies and models report that the outbreak of arctic air bringing freezing temperatures to the lower United States is consistent with the climate disruption expected on a warming planet where the Arctic heats up faster and cold air is displaced to the south.

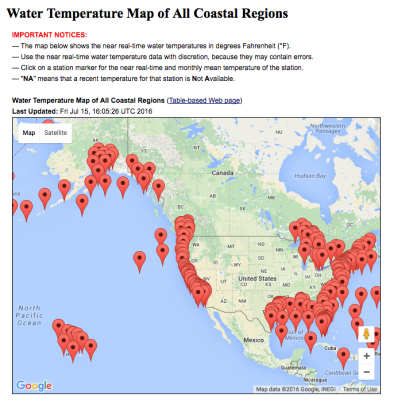

Unusually warm offshore waters also amplified the temperature contrast between land and ocean surfaces. This temperature contrast is what generally fuels nor’easters. These conditions over the Atlantic are consistent with the long-term climate change trends that intensify nor’easters.

While climate change warms the planet as whole, it also disrupts regional weather patterns, sometimes displacing cold air to the south. The overall warming trend continues but cold conditions can move. The record setting heat events recently observed further north in parallel to cold conditions in the continental US are consistent with this pattern of disruption.

Related Content

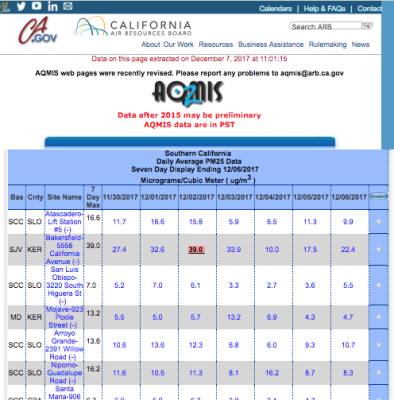

Thomas Fire 2017

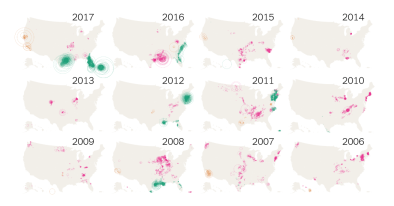

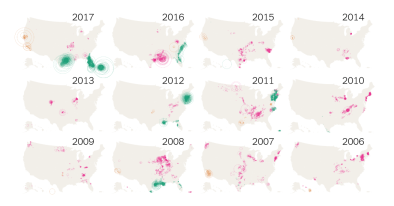

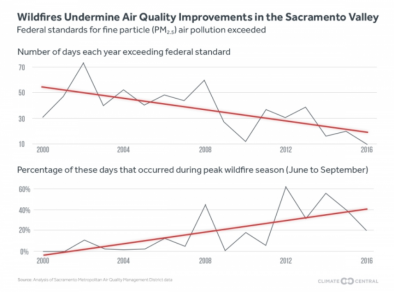

Higher temperatures, drier conditions, increased fuel availability, and growing warm seasons—all linked to climate change—are increasing wildfire risk in California.

In 2017, the combination of a wet winter followed by extreme heat and dry conditions has fueled record wildfires in many Western states.[1]

In early December, a series of fires extended this trend when they erupted in the mountains north of Ventura and Los Angeles, California.

The Thomas Fire, which began on the evening of December 4, is the largest blaze and grew quickly to nearly 31,000 acres (50 square miles) in less than 12 hours.[2] As of January 1, 2018, the Thomas Fire was 92 percent contained and had burned 281,893 acres establishing it as largest fire in California recorded history.[3][4] A mixture of dry foliage, low humidity and high sustained winds of more than 30 miles per hour led to its explosive growth, according to Fire Sgt. Eric Buschow.[5] Other major fires included the Creek and Rye events.

Research indicates a direct causal link between human-induced climate change and increased wildfire risk in California.[6] Climate change has contributed to California's longer fire seasons, the growing number and destructiveness of fires and the increasing area of land consumed.[7][8]

Related Content

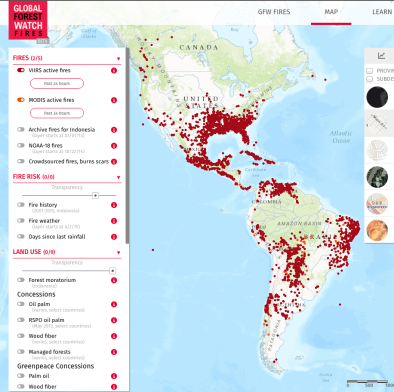

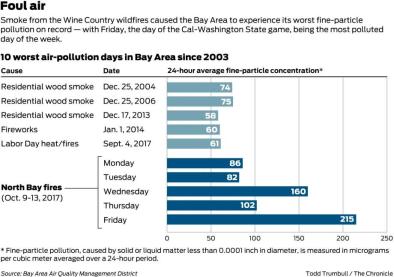

California Wine Country Fires October 2017

Trends in California driven by climate change—including higher temperatures and drier conditions—are elevating the risk of dangerous and destructive wildfires across California and the western United States.

On October 8, a group of fires exploded across a wide swath of Northern California.[1] Taken as a group, the fires are among the worst on record in the state in terms of lives and property lost.[2][3] After just one week, the fires have killed at least 41 people, burnt more than 200,000 acres, destroyed or damaged more than 5,500 homes, and displaced 100,000 people.[4] Governor Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency in Butte, Lake, Mendocino, Napa, Nevada, Orange, Sonoma and Yuba counties.[5]

By the end, the Wine Country fires killed 42 people, destroyed 8,700 homes and buildings, and burned 245,000 acres.[6] The event was deadliest, most destructive, and one of the largest fires in California history.[7][8][9][10]

The combination of a wet winter followed by extreme heat and dryness has fueled record wildfires in many Western states.[11] Climate change compounds the risks of wildfires by extending the length of the fire season and adding to the intensity of droughts and heat waves. Park Williams, a climate and drought expert, noted, “... the combination of dry fuel, extreme heat and climate change is a recipe for what we are seeing."[12]

Related Content

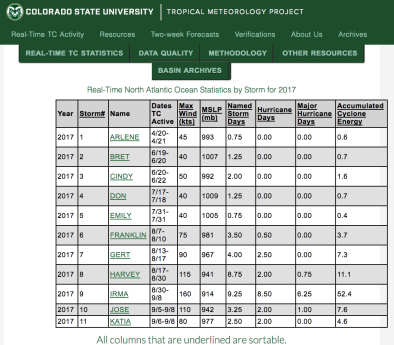

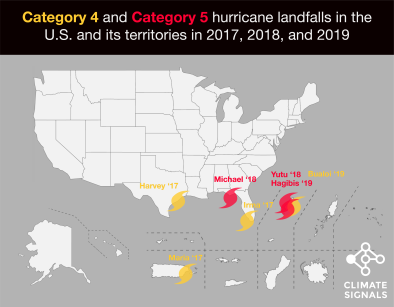

Hurricane Maria 2017

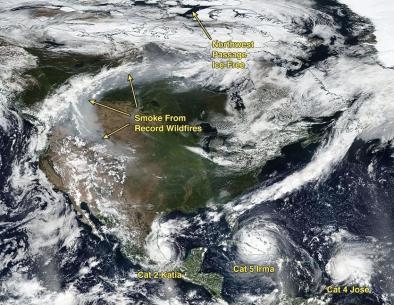

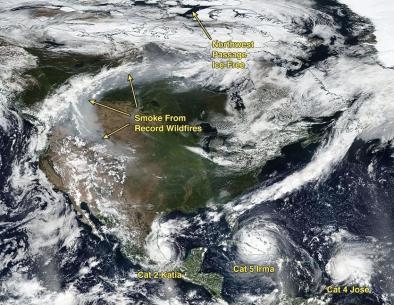

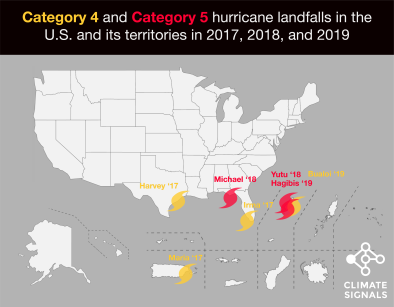

The record-breaking rainfall and flooding driven by Hurricane Maria—as well as Hurricanes Harvey and Irma just weeks before—is consistent with the long-term trend driven by climate change.

Hurricane Maria made landfall in Dominica as a Category 5 hurricane on September 18,[1] then hit southeast Puerto Rico on September 20 with 155 mph winds and a central pressure of 917 millibars.[2] It was the third strongest storm to make landfall in the United States.[3] "1,000-year" rains inundated much of eastern and northwestern Puerto Rico.[4] The storm knocked out power to the entire island of Puerto Rico, home to 3.5 million people, leading to a prolonged humanitarian crisis.[5]

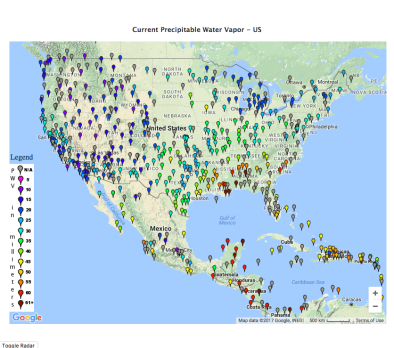

Extreme rainfall is increasing worldwide due to climate change. In Puerto Rico, rain falling in very heavy events increased at least 33 percent from 1958-2012. Seas are now higher due to global warming, so storm surge drives much further inland. There has also been a global increase in the observed intensity of the strongest tropical cyclones, correlated with observed trends in sea surface temperatures in recent decades.

Related Content

Chart: Increasing flood claims in a changed climate

Animated GIF

[published Nov 2017]

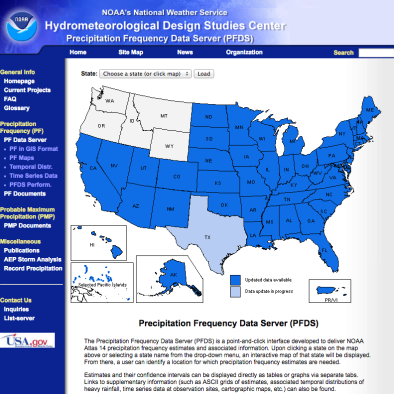

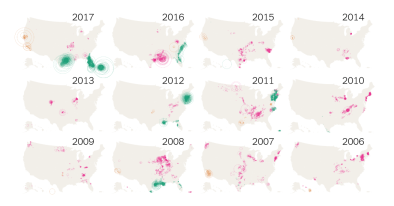

NFIP claims rise alongside upward trends in extreme storm frequency . . .

The increasing frequency of US National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) claims parallels the increasing frequency of extreme rainfall and flooding in the United States.

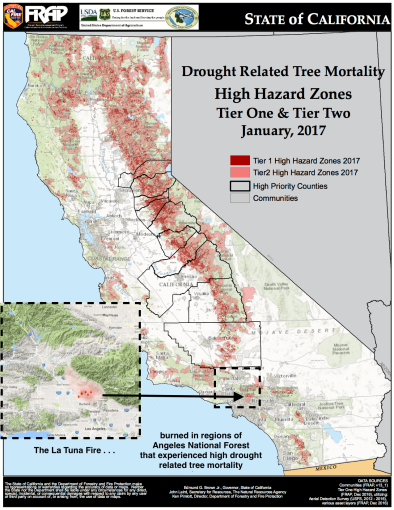

La Tuna Fire September 2017

Higher temperatures and drier conditions—both linked to climate change—are increasing wildfire risk in California.

The La Tuna Fire erupted north of downtown Los Angeles and, at more than 7,000 acres, the fire is the largest to burn within Los Angeles' city limits.[2]

While small compared to the biggest fires in California's history,[1] the La Tuna Fire is notable for its proximity to a major city and its rapid growth amid unseasonably warm temperatures. The fire also erupted at the edge of the Angeles National Forest, a region where bark beetle activity has increased in recent years of extreme heat and drought.

Related Content

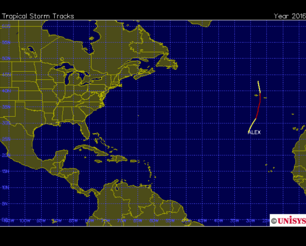

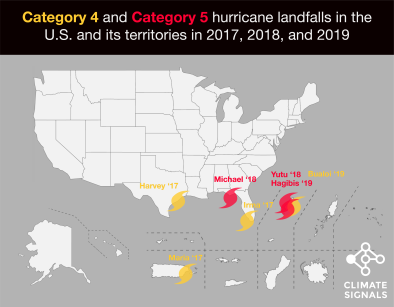

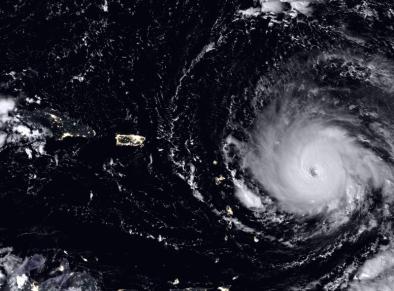

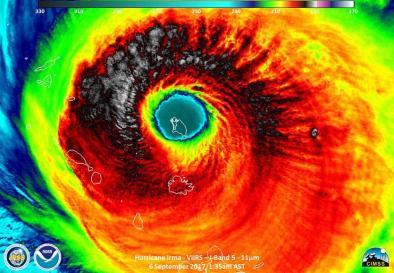

Hurricane Irma 2017

Overview

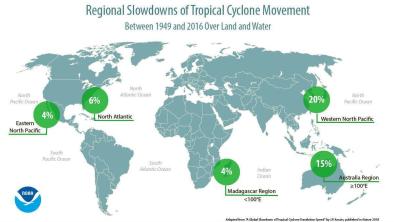

Climate change is amplifying the damage done by hurricanes, by elevating sea levels and thus extending the reach of storm surge, and by loading storms with additional rainfall and thereby increasing flood risk.

Climate change may also be driving the observed trend of increasing hurricane intensity[1] as well as the observed trend of more rapidly intensifying hurricanes.[2][3]

In addition there is significant evidence linking climate change to the observed shift in the track of hurricanes such as Irma toward the US coast.[4]

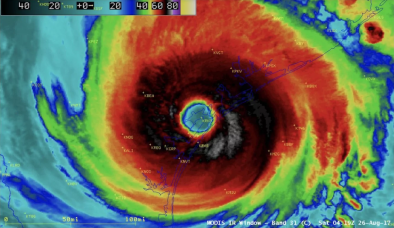

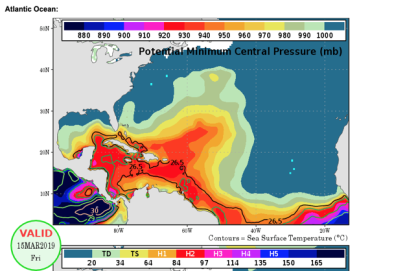

Hurricane Irma maintained maximum wind speeds of at least 180 mph for 37 hours, longer than any storm on Earth on record, passing Super Typhoon Haiyan, the previous record holder (24 hours).[5] Irma’s maximum accumulated energy over 24 hours was the highest for any Atlantic hurricane on record.[9] The storm intensified into a Category 5 with 185 mph winds on September 5, making it the most powerful Atlantic hurricane ever recorded outside of the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico where warmer waters make those areas more prone to stronger cyclones.[6]

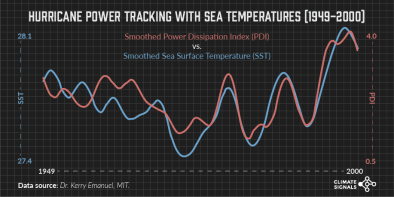

Hurricanes are fueled by available heat. As global warming heats sea surfaces, the energy available to power hurricanes increases, raising the limit for potential hurricane wind speed.[7]

Irma intensified in the Atlantic from September 4 to 5 as it entered a region of sea surface temperatures ranging from 0.9°F to 2.25°F (0.5°C to 1.25°C) above average, relative to a 1961-1990 baseline.[8]

Related Content

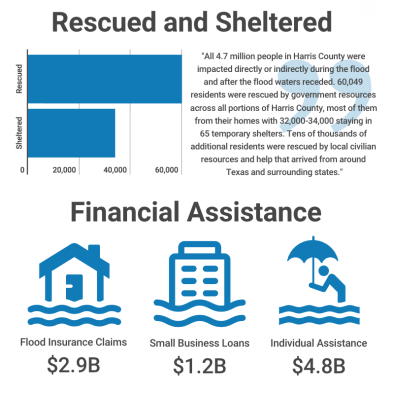

Hurricane Harvey 2017

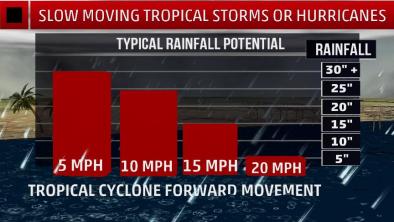

Climate change raises or amplifies the three primary hazards associated with hurricanes: storm surge, rainfall, and the power ceiling, aka potential speed limit, for hurricane winds.

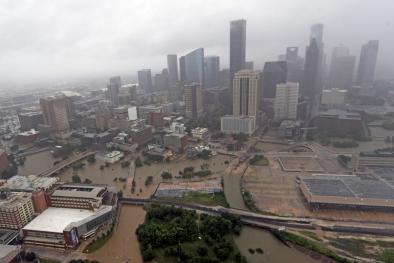

In the case of Hurricane Harvey, extreme precipitation was most notable. Harvey set a new national tropical cyclone rainfall record of 60.58 inches near Nederland, Texas.[1] At least five attribution studies found that global warming added to the deluge of rainfall dumped by Hurricane Harvey., and climate change was responsible for up to $67 billion of Harvey's $90 billion price tag.[2] A warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor, feeding more precipitation into all storms including hurricanes, significantly amplifying extreme rainfall and increasing the risk of flooding.[3][4]

In addition to extreme precipitation, Harvey intensified rapidly amid sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico up to 2.7 - 7.2°F (1.5 - 4°C) above average, relative to a 1961-1990 baseline.[5] As climate change warms sea surfaces, the heat available to power hurricanes has increased, raising the limit for potential hurricane wind speed and with that an exponential increase in potential wind damage.

Related Content