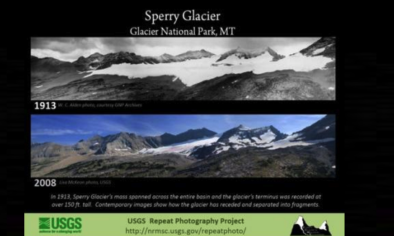

Glacier National Park Glacial Retreat 1938 -

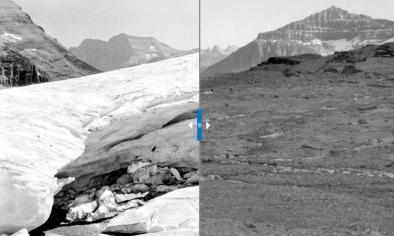

The effects of climate change in Glacier National Park are well-documented. Glacier recession since the early 20th century is well underway, and many glaciers have already disappeared. In 2010, the US Geological Survey estimated there were only 25 glaciers larger than 25 acres remaining in the park, compared to an estimated 50 in 1968, and an estimated 150 in 1850, most of which were still present in 1910. With warmer temperatures and changes to the water cycle driven by climate change, scientists predict Glacier National Park will be glacier-free by 2030. However, glacier disappearance may occur even earlier, as many of the glaciers are retreating faster than their predicted rates.

Glacier Park has lost most of its glaciers since 1910

The mountains and valleys of Glacier National Park were sculpted by the action of glaciers over hundreds of thousands of years of glacial advance and retreat.[1] In 1850, at the end of the Little Ice Age, there were an estimated 150 glaciers in the area that is now Glacier National Park.[1] By 1968, these had been reduced to around 50.[1] Today the number of glaciers in the park is 25, many of which are remnants of what they once were.[1] Rapid retreat of mountain glaciers is not just happening in the park, but is occurring worldwide. If the current rate of warming persists, scientists predict the glaciers in Glacier National Park will be completely gone by the year 2030, if not earlier.[2][3]

Glacier retreat is strongly tied to temperature and precipitation

The glaciers of Glacier National Park, like most worldwide, are melting as long term mean temperatures increase.[2]

Analysis of weather data from western Montana shows an increase in summer temperatures and a reduction in the winter snowpack that forms and maintains the glaciers. Since 1900 the mean annual temperature for GNP and the surrounding region has increased 1.33°C,[4] which is 1.8 times the global mean increase. Spring and summer minimum temperatures have also increased,[4] possibly influencing earlier melt during summer. Additionally, rain, rather than snow, has been the dominant form of increased annual precipitation in the past century.[5] Despite variations in annual snowpack, glaciers have continued to shrink, indicating that the snowpack is not adequate to counteract the temperature changes.

Additional climate signals in Glacier Park

Two rare alpine insects—native to the northern Rocky Mountains and dependent on cold waters of glacier and snowmelt-fed alpine streams—are imperiled due to climate warming-induced glacier and snow loss.[6]

Mountain snowpacks hold less water and have begun to melt at least two weeks earlier in the spring.[8] This impacts regional water supplies, wildlife, agriculture, and fire management.[7]

Related Content