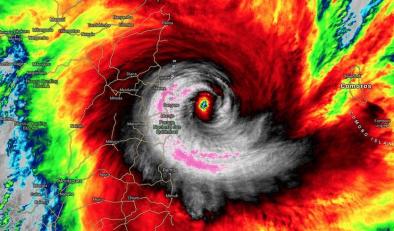

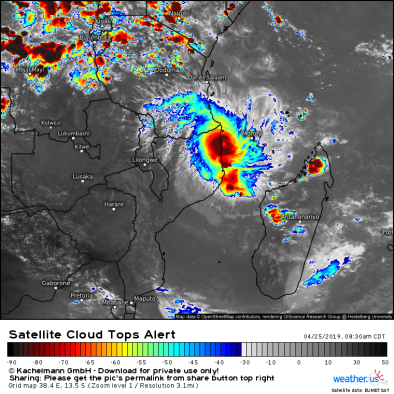

Tropical Cyclone Kenneth 2019

Category 4 Cyclone Kenneth made landfall on April 25 in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique making it the strongest cyclone on record in the country and one of the strongest cyclones to make landfall in Africa.

Kenneth is also the strongest cyclone on record to make landfall in the Indian Ocean archipelago nation of Comoros, where violent winds caused landslides, flash flooding and killed three people.[2]

The superstorm comes just six weeks after Cyclone Idai, which devastated parts of Mozambique in March. The country is now at risk of extreme rainfall, flooding, and mudslides over several days.

Warming seas and a wetter atmosphere due to climate change are supercharging the deluge delivered by tropical cyclones like Kenneth, increasing flood risk.

Climate science at a glance

- Global warming is increasing water vapor in the air, which in turn is fueling extreme rainfall, increasing the threat of flooding.[1]

- Global warming is also heating up sea surface temperatures, which in turn raises the maximum potential energy a storm can reach.[2]

- The fingerprint of human-caused climate change has been found in the slowdown, or stalling, of tropical cyclones worldwide.[3]

- Tropical cyclones have shifted toward the poles and this shift is likely due to global warming.[4][5]

- Research to date does not show an increase in the frequency of tropical cyclone landfalls over the south‐west Indian Ocean and future projections are not clear.[6] But with two hurricanes occurring back-to-back, we may be seeing a new signal emerge.

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signals #1 and #2: Extreme Precipitation Increase and Sea Surface Temperature Increase

Climate change is fueling extreme rainfall and dramatically increasing rainfall across many types of storms, and an increase in rainfall rates is one of the more confident predictions of the effects of climate change on tropical cyclones.[1][2]

As the global average temperature increases, so too does the ability of the atmosphere to hold and dump more water when it rains.[1] Atmospheric water vapor has been increasing.[7][8] And the observed increases have been studied and formally attributed to global warming.[9][10][11]

Tropical cyclones are fueled by the heat available in the ocean surface. Warming seas have increased the potential energy available to passing storms, effectively increasing the power ceiling or speed limit for these cyclones.[2][12]

Observations consistent with climate signals #1 and #2

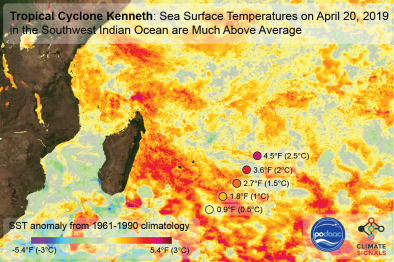

- Sea surface temperatures were up to 4°F above the 20th century average in the days leading up to Cyclone Kenneth's rapid intensification.[13]

- Favorably warm conditions aided Kenneth's rapid development to a Category 4 storm with top sustained one-minute winds were pegged at 120 knots (140 mph) by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center.[14]

- According to AccuWeather Senior Meteorologist Kristina Pydynowski, "A flooding disaster can unfold in Cabo Delgado where Kenneth slammed onshore. Additional downpours into this weekend can push the AccuWeather Local StormMax™ to 600 mm (24 inches)."[18]

Climate signal #3: Storm Surge Increase

Global warming is driving up sea level, which greatly extends the reach of storms along low-lying areas. Increases in storm surge related to climate change can be due to rising seas, increasing size, and increasing storm wind speeds.[2][15]

Coastal communities are at risk. A small vertical increase in sea level can translate into a very large increase in horizontal reach by storm surge depending upon local topography. Forty-percent of Mozambique’s population lives in coastal districts.

In the United States from 1963 to 2012, 88 percent of storm-related fatalities occurred in water-related incidents; storm surge caused 49 percent and freshwater floods due to heavy rainfall caused 27 percent.[16] Globally, storm surge kills an average of 13,000 people each year.[17]

Observations consistent with climate signals #3

- The Quisanga Islands, which includes several resorts, were likely quite hard hit by Kenneth’s winds and by a storm surge that could have been as high as 3 -5 meters (10 – 16 feet), according to RSMC-La Reunion.[14]

Climate signal #4: Tropical Cyclone Steering Change

Global warming affects large scale weather patterns and the weather systems, such as tropical cyclones, embedded within. Research has documented several recent changes in tropical cyclone steering such as increased stalling and shifts toward higher latitudes.

Observations consistent with climate signals #4

- In records going back 50 years, far northern Mozambique has no record of storms of even minimal hurricane strength.[14] The landfall location (12°S) is quite close to the equator, in a latitude range where it becomes more difficult for cyclones to gather enough atmospheric spin to develop.[14] Only a couple of tropical depressions and tropical storms have made landfall this far north in Mozambique or in Tanzania in the several decades of satellite coverage.[14]

- Kenneth is expected to stall for several days. This stalling is consistent with the long-term trend of increasing stalling of tropical cyclones that has been observed worldwide and attributed to climate change.[3]