Western Wildfire Season 2020

Climate change was a key driver of the unprecedented fires that caused significant damage and devastation across the western US during the 2020 fire season. Rapid snowmelt in May, early season heat waves in late spring, the absence of the Southwest monsoon, anomalously warm seasonal temperatures, record heat waves in early fall, the hottest August through October period in western US history, and very high vapor pressure deficits had the effect of drawing moisture out of the fuels, priming the environment for explosive fire behavior.

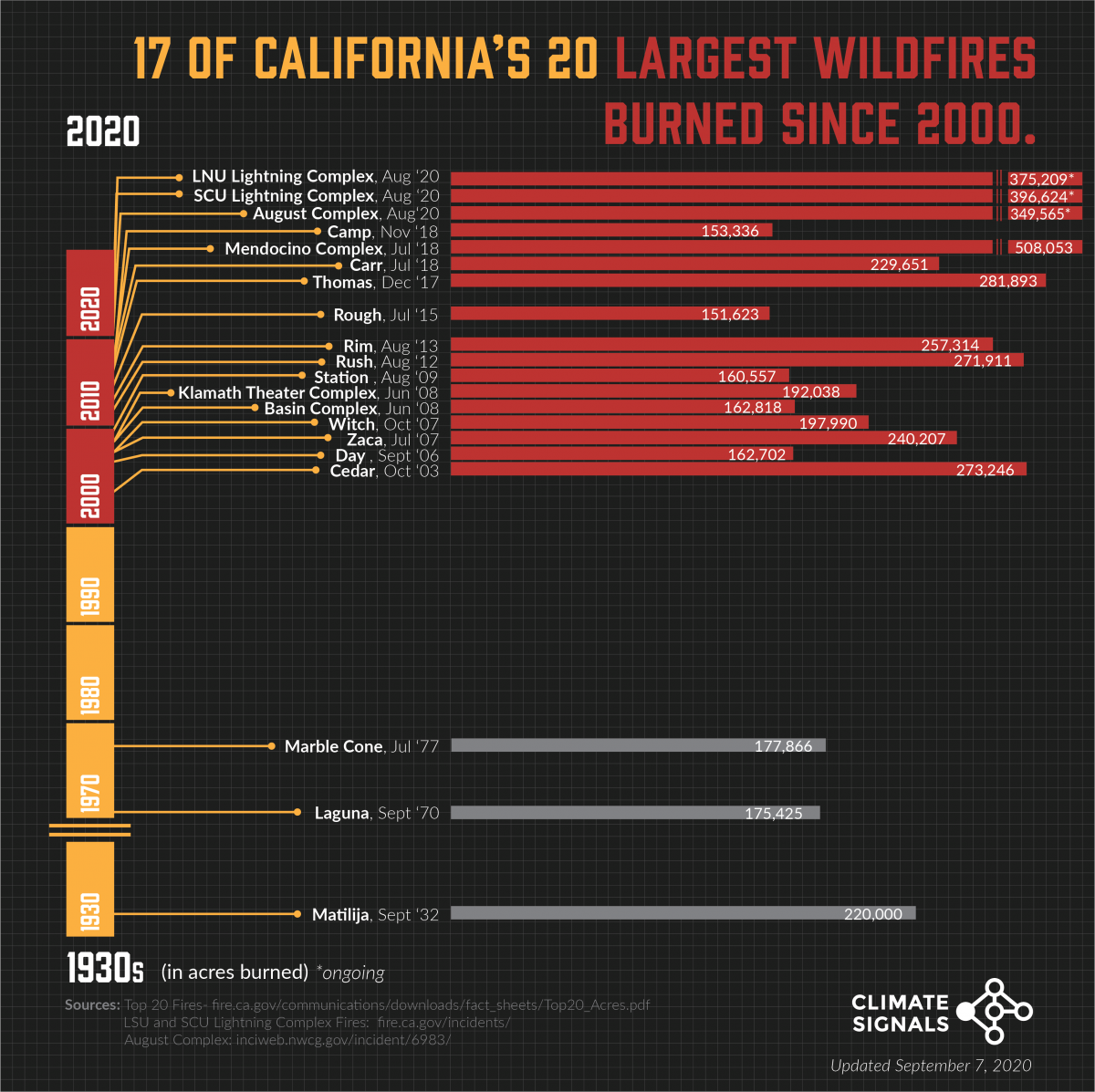

In August, record heat, low humidity, and widespread dry lightning spawned nearly 1,000 fires in California. The situation escalated in September when seasonal offshore winds fanned the flames. Five of California’s six largest fires occurred in 2020, including the August Complex Fire, the largest fire in state history at 1.03-million acres. In early September, explosive fires in Oregon burned 900,000 acres in three days, almost double the amount that typically burns in an entire year. Washington state, which saw an average of 300,000 acres burn during the previous five years, saw 500,000 acres burn in just a few days. By mid-October, the Cameron Peak Fire in Colorado had grown to become the largest fire in state history. Colorado and California set new records for total acres burned in a single season. By December 31, 2020, the National Interagency Fire Center reported that US wildfires burned 10.27 million acres – the highest yearly total since accurate records began in 1983.

Climate science at a glance

- Climate change makes it more likely that fires turn into catastrophic blazes through warmer temperatures, increasing the amount of fuel (dried vegetation) available, and reducing water availability through earlier snowmelt and higher evaporation.

- The frequency of hot, dry, and windy weather has increased in much of the US.[1]

- Climate change has doubled the area burned in the western US.[2]

- In California alone, there has been a fivefold increase in burned area extent in forests since 1972, coinciding with a period of much warmer and drier conditions.

- The fire season has increased by more than two months in the western US, largely due to climate change.[3]

- Climate change has doubled the frequency of autumn days with extreme fire weather conditions in California.[4]

Background information about the 2020 western wildfire season

What factors contribute to worsening wildfires in the western US?

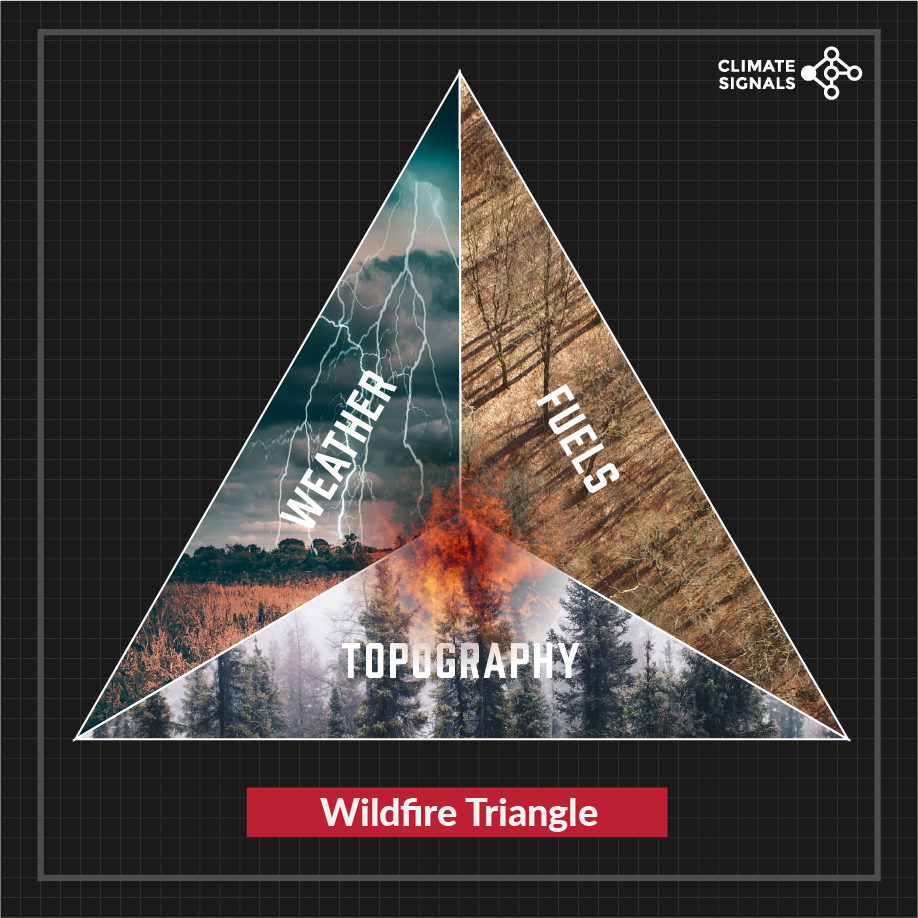

Wildfire disasters are due to the combination of climate change, human land-use and forest management, which can make fires more severe, and the exposure to and vulnerability of populations to fires.[5] Fire officials explain wildfire behavior using the fire triangle, pictured right. Wildfires are driven by three elements: topography (mountainous versus flat), vegetation (the fuel source), and weather. As topography and weather generally cannot be controlled, most fire prevention in wildlands focuses on removing dry vegetation and encouraging healthier ecosystems which won’t burn as easily. In some regions, forest mismanagement has increased wildfire risk.

Wildfire disasters are due to the combination of climate change, human land-use and forest management, which can make fires more severe, and the exposure to and vulnerability of populations to fires.[5] Fire officials explain wildfire behavior using the fire triangle, pictured right. Wildfires are driven by three elements: topography (mountainous versus flat), vegetation (the fuel source), and weather. As topography and weather generally cannot be controlled, most fire prevention in wildlands focuses on removing dry vegetation and encouraging healthier ecosystems which won’t burn as easily. In some regions, forest mismanagement has increased wildfire risk.

What were recent western wildfire seasons like?

In 2018, the Camp Fire in Northern California was the costliest, deadliest and most destructive on record, costing an estimated $16.5 billion, killing 85 people, and destroying more than 18,000 structures. The state also endured its largest wildfire on record—the Mendocino Complex Fire, which burned more than 450,000 acres.

California's total wildfire cost in 2018 was a staggering $24 billion, primarily from the destruction of homes and infrastructure, along with firefighting costs. Nationally, the 2018 wildfire season overtook 2017 as the most expensive, and the two years together caused an unprecedented $40 billion worth of damage. The 2017 record was triple the previous record for US annual wildfire season cost, which was $6 billion in 1991.

The 2019 wildfire season, though less destructive than previous years, was notable for a series of significant late-season fires that burned in California. These late fires are consistent with research showing an increase in autumn wildfire risk in the state due to climate change.[4]

What did experts forecast going into the record-breaking season?

The Climate Prediction Center, which is part of the National Weather Service, forecast a hotter and drier than average summer across much of the West that would intensify already widespread drought in the region, further drying out vegetation and making wildfires worse.

Much of the western US was forecast to see above normal activity. Forecasters anticipated the season would be particularly bad in California due to the combined effect of the most recent winter, which was dry, and the abundance of now dry and flammable vegetation from the previous wet winter.

Last year you’ll remember we had a lot of snow in the mountains, a lot of late-season rain, and we had a slow start to our fire season. That’s not going to be the same this year.

Thom Porter, director of California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

How does COVID-19 intersect with wildfire preparedness and response?

- Prescribed burns: Early in the season, firefighters thin out forests using prescribed, or controlled burns to reduce wildfire risk later in the year. However, some agencies are limiting prescribed burns during the COVID-19 pandemic to prevent any effects from smoke that might further worsen conditions for at risk groups. While putting off prescribed burns may be an important health precaution, it could mean worse wildfires this season, and for seasons to come.

- Base camps: Emergency managers must adapt procedures to limit the risk of contagion. When fighting major fires, base camps can number in the thousands and response efforts can last for weeks, often bringing in resources from out of state. Fire personnel will have to undergo regular health checkups, and daily briefings will likely be held virtually to prevent large gatherings. The Department of Interior has a useful primer on Wildfires & COVID-19.

- Evacuations and displacement: Similarly, emergency managers are having to rethink how to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in an evacuation scenario, and how to safely manage displaced populations. The Red Cross, which operates emergency shelters at the request of local officials, is planning major changes to its sheltering practices this year with a focus on numerous, smaller shelters so that social distancing can be maintained.

Having 500 people in a gym with coronavirus, that’s not a smart way to keep the public safe.

Tony Briggs, CEO for the Central California Region of the American Red Cross

How does COVID-19 intersect with wildfire health concerns?

Preliminary research suggests that wildfire smoke could put firefighters and other vulnerable populations at greater risk from the worst complications of the new coronavirus. Research suggests a link between breathing fine particulate matter, like that in smoke, with worsened outcomes from COVID-19. Another study showed habitually breathing wood smoke decreases the lungs’ abilities to clear out pathogens. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published guidance with key messages about managing wildfire smoke amid COVID-19.

Preliminary research suggests that wildfire smoke could put firefighters and other vulnerable populations at greater risk from the worst complications of the new coronavirus. Research suggests a link between breathing fine particulate matter, like that in smoke, with worsened outcomes from COVID-19. Another study showed habitually breathing wood smoke decreases the lungs’ abilities to clear out pathogens. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has published guidance with key messages about managing wildfire smoke amid COVID-19.

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signal #1: Land surface temperature increase

Humans spark most fires, but global warming makes it much riskier to have that spark light a fire by increasing the size, frequency, intensity and seasonality of western wildfires. Between 1901 and 2016, the average annual temperatures in the Southwest and Northwest increased by 1.6°F (0.9ºC), and nearly 2°F (1.1°C) respectively.

Hotter and drier conditions driven by global warming have doubled the area burned in the western US and increased the fire season in the region by more than two months.[2]

Observations consistent with climate signal #1:

- Hot and dry conditions driven by global warming set the stage for a record-breaking wildfire season in California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, and Colorado.

- In June, Arizona experienced three major fires that were among the top 10 biggest wildfires in state history.

- In August, amid an extreme and prolonged heat wave, major wildfires erupted across the Southwest, including enormous megafires burning in California and Colorado.

- The western US experienced the hottest August through October period on record.

- California set a new state record in early September for the most acres burned in a single year. In an average season, 300,000 acres burn, but in 2020, more than 2 million acres burned by early September. By the end of the year, more than 4.2 million acres had burned, smashing the previous record of 1.98 million acres from 2018.

- Six of California’s 20 largest fires on record occurred during the 2020 fire season. These fires include the August Complex (No. 1), SCU Lightning Complex (No. 3), LNU Lightning Complex (No. 4), Creek Fire (No. 5), the North Complex (No. 6) and SQF Complex (No. 18).

- Oregon State Governor, Kate Brown, said on September 10 that more than 1,400 square miles (900,000 acres) of land had burned across the state in the last three days. That's almost double the amount that typically burns in an entire year. By the end of the season, 1.07 million acres burned, the second-most on record.

We have never seen this amount of uncontained fire across the state... This will not be a one-time event. Unfortunately, it is the bellwether of the future. We're feeling the acute impacts of climate change.

Governor Kate Brown, State of Oregon

- Washington state, which saw an average of 300,000 acres burn each year during the previous five years, saw 500,000 acres burn in just a few days in early September.

- In mid-October, the Cameron Peak Fire becomes largest wildfire in Colorado history. Three of Colorado's top four largest fires occurred in 2020, and the state set a new record for total acres burned in a single season.

Climate signal #2: Extreme heat and heat waves

Due to climate change, extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent, and this spells trouble for wildfire season in the western US. On a hot summer day, a small spark can ignite a raging wildfire, and data shows that many more wildfires burn in hotter years.[3]

Scientists have found a direct link between increasing heat extremes in the West and human-caused climate change.[6] As the West heats up, conditions are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[7] During the period 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West, and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[8][9]

Observations consistent with climate signal #2

- California experienced an unusually high number of early-season heat waves in late spring and early summer.

- A prolonged, record-breaking heat wave primed conditions in August for extreme wildfire behavior in Northern California when a 'historic lightning siege' ignited hundreds of fires.

Climate signal #3: Drought risk increase

The most direct link between climate change and fire is through how dry fuels get. What we've seen in the Western United States is that fuel dryness during the fire season explains around three quarters of the year-to-year variability in burned area extent. That has the effect of drawing moisture out of the fuels and priming the environment. Climate change plays a role through increasing the rate at which the temperatures warm, increasing the rate at which they draw moisture out of fuels.

The most direct link between climate change and fire is through how dry fuels get. What we've seen in the Western United States is that fuel dryness during the fire season explains around three quarters of the year-to-year variability in burned area extent. That has the effect of drawing moisture out of the fuels and priming the environment. Climate change plays a role through increasing the rate at which the temperatures warm, increasing the rate at which they draw moisture out of fuels.

Underlying year-to-year variability, research shows the Western United States in the midst of an extreme megadrought, among the worst in recorded history, and rising temperatures due to human-caused climate change are responsible for about half the pace and severity of the drought.[10]

Observations consistent with climate signal #3

- Colorado experienced an exceptionally bad fire year driven by dry conditions. At least a quarter of the state was in drought since October 2019. By mid-August, almost 94 percent of the state was in drought, with nearly 24 percent categorized as extreme or exceptional drought, the two worst categories. The lack of rain also coincided with a hot summer in Colorado, following a generally warmer-than-average 2020, so far. The end result of little moisture and hot temperatures was a lot of dry vegetation.

- In California, the 2019-2020 water season reflected the underlying megadrought. California had an abnormally dry January, its driest February on record, and the average statewide temperature in winter (Dec-Feb) was 2.7°F above the 1901-2000 average.

- The Southwest monsoon never got started, leaving much of Arizona and New Mexico especially parched. Between mid-June, when the monsoon season traditionally starts, and mid-August, Phoenix received only 0.1 inches of rain. In June, Arizona experienced three major fires among the top 10 biggest wildfires in state history.[11] Arizona’s nonexistent monsoon season pushed fire activity well into the fall with October’s 9,537-acre Horse Fire on the Prescott National Forest.

We're seeing widespread fire activity across California, stretching all the way to Colorado. And it's coincided with a year where at least the southern half of the Western United States is anomalously warm, very high vapor pressure deficits.

John Abatzoglou, associate professor in the Department of Management of Complex Systems at the University of California Merced

Climate signal #4: Lightning risk increase

Lightning occurs during storms with strong updrafts. During these storms, charged ice particles in clouds collide, generating an electric field. If the field is strong enough, electricity can arc to the ground as lightning, which can ignite dry vegetation. Nationwide, about 15 percent of wildfires start this way.

Strikes across the United States are expected to increase with climate change, as warmer air carries more water vapor, which provides the fuel for strong updraft conditions. A 2014 study estimated that strikes could increase by about 12 percent per 1.8°F (1°C) of warming, or by about 50 percent by 2100.

Observations consistent with climate signal #4

- In mid-August during an extreme and prolonged heat wave, northern California experienced what a state fire official described as a “historic lightning siege”, with nearly 11,000 bolts of lightning over 72 hours. The lightning ignited 367 wildfires that burned through more than 350,000 acres over the span of five days. David Romps, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, says, “It is likely that there was more lightning because of global warming."

Climate signals #5 and #6: Snowpack decline and snowpack melting earlier and/or faster

Rapid, early snowmelt means a longer dry season, drier vegetation and larger fires in mid- and high-elevation forests. Warmer springs and summers, and the resulting shifts in snowmelt timing, have helped to drive marked increases in burned area in Western forests since the mid-1980s.[2]

This year, like the previous five to 10 years, has water managers working their worry beads.

Bill Patzert, climatologist

Observations consistent with climate signals #5 and #6

- The western US experienced a sharp snow water drop-off between mid-April and early May due to both above-average temperatures and a lack of precipitation in many areas, including California, the Pacific Northwest, Nevada and southern Colorado.

- Northern California accrued huge rain and snowfall deficits during a record-dry February. Snowpack in the Northern Sierra rebounded during storms in March and April, climbing back to 69 percent of normal by April 9. However, the second half of April was warm and dry, and snowpack plummeted to 19 percent of normal for early May and disappeared by early June, several weeks ahead of schedule.

Related Content