Southern California Mudslides January 2018

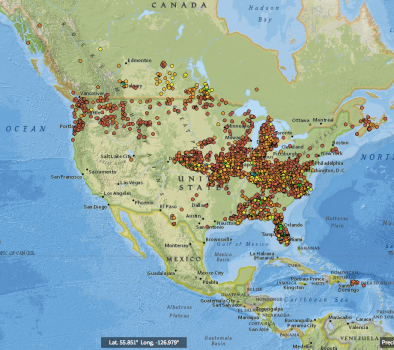

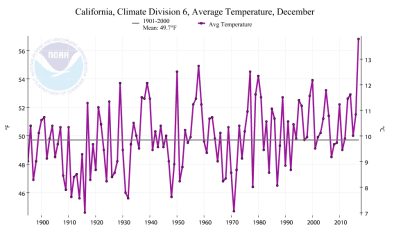

On Tuesday, January 9, flash floods gave way to mudslides that killed at least 17 people and injured dozens of others.[1] The mudslides' severity is directly linked to a series of recent California weather disasters that are consistent with climate change trends. These include years of extreme drought, a 300 day period of record dry days in much of Southern California, a statewide heatwave during the fall, the warmest December on record along California's south coast,[2] and the largest wildfire in California state history, which left a vast burn scar in the regions most affected by the heavy rainfall.

The record Thomas Fire was still not fully contained during the rainfall event, with the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management (NWCG) website listing the fire as 92 percent contained as of January 9 at 11:00am.

The rainfall event itself was consistent with climate change trends in that very heavy amounts of rain fell in short periods of time, which increases the risk of runoff.[3]

According to Noah Diffenbaugh, a professor of Earth Sciences at Stanford University, “This situation that we’re seeing with the pronounced drought punctuated by wet conditions that are producing a lot of runoff — that is exactly what we are seeing intensify in the historical record. And it’s exactly what climate models project for the future.”[4]

Climate science at a glance

- The mudslides followed a series of extreme events with links to climate change, including: the largest wildfire in California history, which was preceded by near record hot summer and fall temperatures in the region[1][2], a record setting statewide heat wave, the driest 300-day period on record in Southern California[3], and five years of acute drought.

- Heavy rainfall rates, like those observed during the storm, are a major risk factor for flash flooding and mudslides, and are consistent with climate change trends. As the air gets warmer, there has been an observed increase in rainfall rates, because warmer air can hold and dump more moisture over shorter periods of time.[4]

- Climate change contributes to both flood and drought in California, further polarizing climate conditions, i.e. weather whiplash.

Record heat and drought, followed by record fire, set the stage for flash floods and mudslides—all signals of climate change

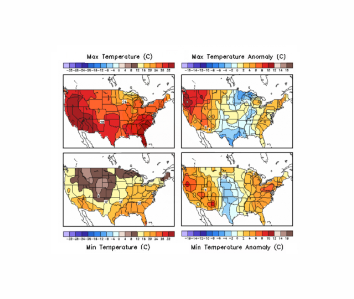

Increasing temperatures

Climate change increases temperature, which causes drier, more flammable, surface conditions, which increase the risk of flash floods and mudslides. The month during which the Thomas Fire scorched the Santa Barbara area was the regions warmest on record at 7.1°F above average.[5]

In September, a heat wave described as, "The greatest statewide heat wave ever recorded in California,"[6] contributed to the rapid growth of the La Tuna Fire, the largest fire to burn within Los Angeles' city limits. A smaller but still-damaging mudslide was reported in a Burbank neighborhood affected by the La Tuna Canyon Fire last September.[7]

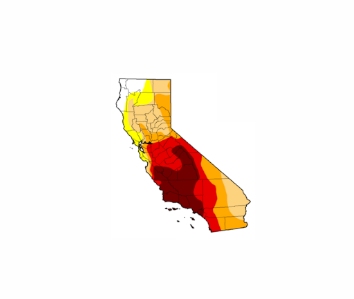

Drought risk

Warm temperatures[1][2][5] helped dried out soils and amplify drought, wildfire, and runoff risk in southern California. On January 7, 2018, the previous 300 days were the driest such period on record across most of Southern California.[3]

The southwestern United States has already begun a long-predicted shift into a decidedly drier climate.[8] From 1979 to 2015, human-caused climate change was responsible for more than half of the dryness of western forests and the increased length of the fire season.[9]

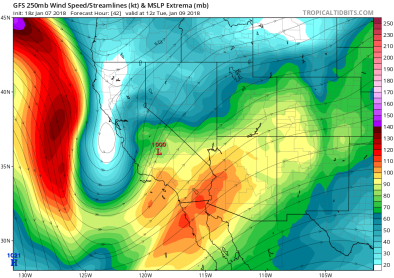

Changing weather patterns due to climate change are also at least partly responsible for the dramatic decline in precipitation during two back-to-back winters in California—the winters of 2012-2013 and 2013-2014—that contributed to the severity of the California drought. Researchers have linked climate change to the circulation patterns that produced the unprecedented high-pressure weather pattern known as the “ridiculously resilient ridge” that blocked storms from the state.[10][11]

A study looking at data from 1979 to 2014 finds up to a 25 percent decrease in precipitation in the US Southwest related to an increase in high pressure, anticyclonic conditions during this time in the North East Pacific.[8]

Wildfire and runoff risk

Extreme heat and years of ongoing drought[12], both linked to climate change, are increasing wildfire risk in California.[8] Recent decades have seen a profound increase in forest fire activity over the western United States,[13] and the fingerprint of global warming has been been found in California wildfires.[14]

According to climate scientist, Daniel Swain, fire makes slopes more susceptible to mudslides for a few reason:[3][15]

- flames can strip hillsides of plants that would otherwise anchor dirt in place,

- fires can also physically change the soil, leaving behind a layer of water-repellant dirt near the surface (in part due to the melted remains of the resin-like coat plants in the area have on their leaves),[16] and

- plants are unable to slow the rate at which rainfall reaches the dirt, leaving more to race down hillsides as runoff.

The Thomas Fire's burn scar was a major factor in the heavy runoff observed in Santa Barbara county. The very recent severe wildfire activity presented a high risk of serious, life-threatening conditions. Record dryness, combined with record heat [1][2][5] helped fuel the Thomas Fire, California's larges wildfire on record. The fire was not fully contained by the start of the flash flood event on January 9.

Heavy rainfall rates, even as the overall climate gets drier, are a clear signal of climate change

Heavy rainfall rates, like those observed during the storm, are consistent with climate change trends and increase the risk of runoff.[4] A total of 0.54 inches was reported in just five minutes at Montecito and 0.86 inches in 15 minutes at Carpenteria. That's a 1-in-200 year rainfall rate, according to Robert Munroe, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard.[17]

Any storm that has intensities greater than about 10 millimeters/hour (0.4"/hour) poses the risk of producing debris flows when occurring over fire-scarred areas.

Rainfall totals were also striking; early estimates suggested that precipitation amounts in the southern part of California from January 6-11 were 150-400 percent of normal for that time of year.[18]

Related Content