Western Wildfire Season 2019

Warmer and drier conditions due to climate change are increasing the size, frequency, intensity and seasonality of wildfires in the western US.

The 2019 season follows two years during which California experienced its deadliest and most destructive fires on record. This year's season started off quiet, but fire analysts warned the season would be significantly above normal through at least October.[1] Extreme fire conditions picked up in October, sparking several rapidly spreading fires including the Kincade and Tick Fires.

Climate science at a glance

-

Human-caused climate change is increasing wildfire activity across forested land in the western United States.[1][2]

-

Warmer temperatures due to climate change dry out grasses and other wildfire fuels, and drier fuels make it easier for fires to start and spread.

-

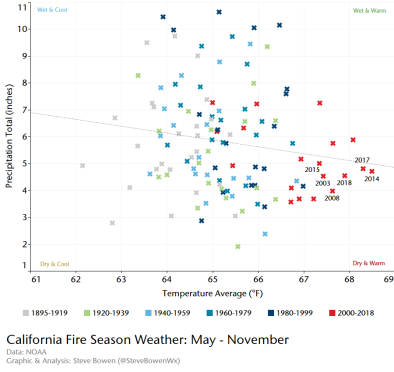

The flare-up in fire activity over the past decade has coincided with an observed trend toward hotter, drier and longer-lasting fire seasons.

-

Climate change has lengthened the window of time each year with weather that is conducive to forest fires.[1]

-

More than half of Western states have experienced their largest wildfire on record since 2000.[3]

-

Wildfires threaten individual safety and property and can worsen air quality locally and in the surrounding region, causing significant public health impacts.

-

The costs associated with health effects, loss of homes and infrastructure, and fire suppression are increasing.

Background information

When is the western wildfire season?

The western wildfire season generally starts in mid-May and lasts until mid-November. It does not have a fixed calendar date, and he amount of rain in the preceding and following seasons changes its span year to year. In California, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) states the length of the fire season is estimated to have increased by 75 days across the Sierras, corresponding with an increase in forest fire extent across the state.

Doesn't forest management also play a role in worsening wildfire seasons?

Human-caused climate change, land use, and forest management all play a role in increased wildfire risk. Climate change leads to warmer and drier conditions that increase the frequency of large fires; human activities have expanded into areas of uninhabited forests, shrublands, and grasslands increasing human exposure[4]; and increased fire suppression practices have reduced natural fires and led to denser vegetation, resulting in fires that are larger and more damaging when they do occur.

Have scientists identified the fingerprint of climate change on worsening western wildfires?

The direct influence, or fingerprint, of climate change is easier to identify in some trends than others. In the case of wildfires, it's often challenging for scientists to parse out the influence of climate change versus other natural and human factors. This is because wildfires are heavily influenced by human land-use and management practices in addition to the weather and climate.[5]

That said, hotter and drier conditions due to human-caused climate change make it easier for fires to spread. Observations show that climate change has already had a hand in shaping fire seasons, especially in California and the western United States.

Climate signal breakdown

Climate signal #1: Extreme heat

Due to climate change, extreme heat and heatwaves are becoming more frequent, and this spells trouble for wildfire season in the western US. On a hot summer day, a small spark can ignite a raging wildfire, and data shows that many more wildfires burn in hotter years.[6]

Between 1901 and 2016, the average annual temperatures in the Southwest and Northwest increased by 1.6°F (0.9ºC), and nearly 2°F (1.1°C) respectively. Scientists have found a direct link between increasing heat extremes in the West and human-caused climate change.[7] As the West heats up, conditions are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[8] During the period 1980 to 2010, there was a fourfold increase in the number of large and long-duration forest fires in the American West, and the size of wildfires increased severalfold.[9][10]

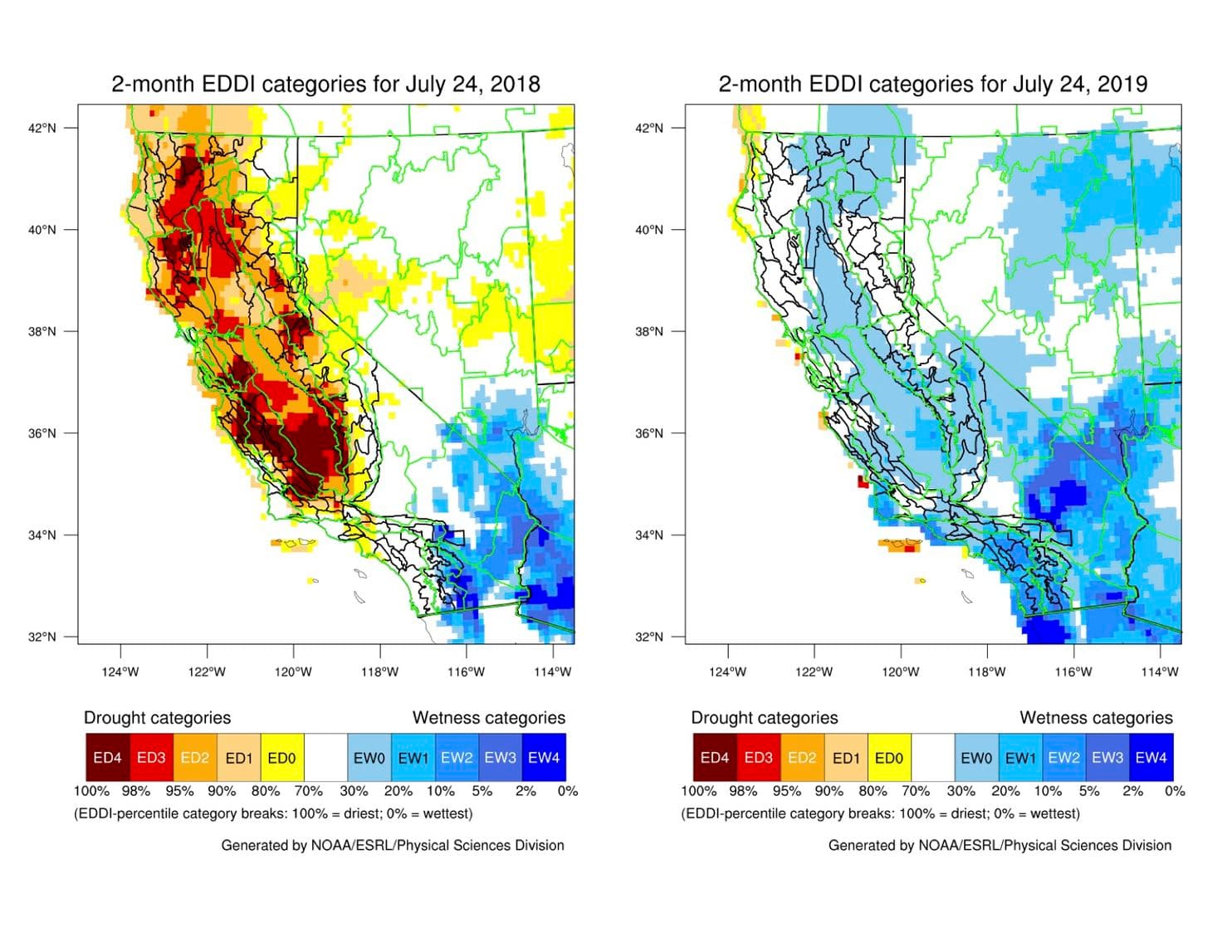

Wet rainy seasons—like the western US had this year—create a special risk because heavy precipitation increases the amount of potential fuel that hot summer temperatures can dry out. The wet winter and spring has meant the 2019 fire season got off to a slow start. However, as moisture levels decrease, all the grasses and fuels are drying out and becoming ready to burn.

There is a link between a warmer, drier climate and wildfires.

- Jennifer Balch, fire ecologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder[11]

It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that forests burn when it's warm and dry, and we've seen more of those years recently.

- John Abatzoglou, climate and wildfire expert at the University of Idaho[11]

Heat in connection with 2019's wildfires

- Although California had a wet winter, it was followed by record-breaking heat waves over the summer and fall.[12]

- A heat wave at the end of July had inland valley temperatures soaring into the upper 90s and 100s from Riverside to Redding, igniting blazes near Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Monterey and Big Sur.[13]

Climate signal #2: Land surface drying increase

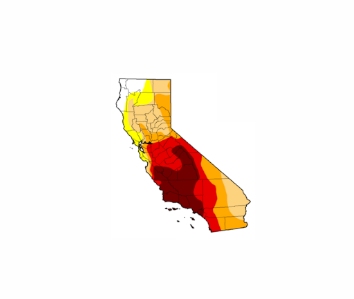

Observations show a direct link between climate change, vapor pressure deficits (VPDs, this is a way of measuring dryness, see background), and increased wildfire risk in the western United States. From 2000 to 2015, climate change enlarged the area of forested land experiencing extremely arid conditions during the fire season by 75 percent.[1] During this same period, high temperatures and VPDs also added nine additional days per year of high fire potential.[1] A climate change fingerprinting study looking at the 2015-2016 western wildfire season found that human-caused climate change quintupled the risk of extreme vapor pressure deficits, which contributed to an active fire season.[14] Looking further back in time, human-caused climate change accounts for 55 percent of observed increases in fuel aridity from 1979-2015 across western forests.[1]

Drought and dryness in connection with 2019's wildfires

Drought and dryness in connection with 2019's wildfires

-

The first week of August, Brent Wachter, a predictive services meteorologist for the Northern California region stated, “Fuels are starting to really dry out due to the heat. We’re seeing shrubs contribute more to fire growth than we were two weeks ago.”[13]

Climate signal #3: Longer fire season

Climate change has lengthened the window of time each year with weather that is conducive to forest fires.[1] The length of the western wildfire season increased by nearly 80 days from the 1980s to early 2000s, with half the increase due to earlier ignitions and half to later control.[6] A separate study looked at the period from 1980 to 2010 and found the length of the fire season expanded by 2.5 months.[9]

Snowpack, which is critical to water supply during the hot and dry summer season, is melting earlier and faster in the spring, and warmer temperatures are lasting longer into the fall. The result is a longer wildfire season and conditions that are primed for wildfires to ignite and spread.[8] During the period 2000-2015, climate change accounts for nine additional days per year of high fire potential.[1]

The length of the fire season is increasing in the Mountain West.

- Matthew Hurteau, associate professor at the University of New Mexico studying climate impacts on forests[15]

A lengthening fire season in connection with 2019's wildfires

- In western Washington, this year's fire danger reached above-normal levels in the region a full three months earlier than at any time in more than 10 years, driven partly by an abnormally dry winter.[16]

Climate signal #4: Atmospheric blocking increase

"Blocks" in meteorology are large-scale patterns in the atmosphere that are nearly stationary, effectively "blocking" westerly winds and the normal eastward progression of weather systems. Blocking events in the western US are causing unusually prolonged hot and dry periods.

There is evidence suggesting that this pattern of prolonged heat and dryness in the West is linked to climate change.

Related Content