Wildfires

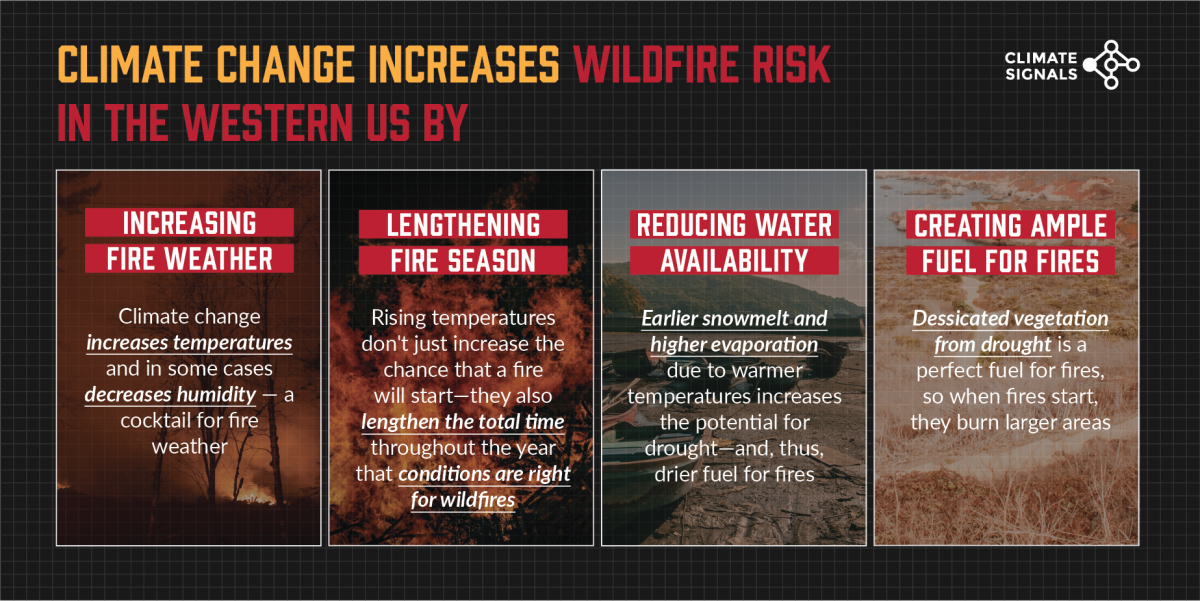

Climate change is increasing the size, frequency, and intensity of wildfires as well as the length of the fire season. All fire needs to burn is an ignition source and plenty of fuel. While climate change might not ignite the fire, it is giving fires the chance to turn into catastrophic blazes by creating warmer temperatures, increasing the amount of fuel (dried vegetation) available, and reducing water availability through earlier snowmelt and higher evaporation. Climate scientists have already identified the telltale fingerprint of climate change on wildfire activity in the past decade.

How has climate change already worsened US wildfires?

Climate change has increased the frequency of hot, dry, and windy weather in much of the US.[1]

Climate change has doubled the area burned in the Western US.[2]

The fire season has increased by more than two months in the Western US, largely due to climate change.[3]

Climate change has doubled the frequency of autumn days with extreme fire weather conditions in California.[4]

What is a wildfire?

A wildfire is a fire that burns out of control in the wilderness. Wildfires can burn in a variety of ecosystems including forests and grasslands. Wildfires can start from natural causes such as lightning strikes, or by humans such as carelessness with a campfire, but climate change impacts the growth and intensity of a wildfire.

How does climate change affect fire weather & fuel availability?

Fires are integral to a natural, thriving ecosystem. However, climate change exacerbates wildfires by creating hotter, windier, and drier weather conditions, and by drying out otherwise healthy vegetation, increasing the amount of available fuel. In these conditions, fires not only occur more frequently, but burn more intensely over larger areas.

Climate change has significantly increased air and land temperatures in the Western US. These higher temperatures can make droughts worse. Warmer winters also mean less snowpack or earlier snowmelt, while warmer summers mean higher evapotranspiration – further increasing and drying out already parched soil and plants.[2] These conditions, along with high winds, can lead to record-breaking wildfires. In some cases, the extreme heat and dryness can cause explosive fires that burn hundreds or thousands of acres in just a few days.

How does climate change affect the fire season & precipitation?

Rising temperatures don’t just increase the chance that a fire will start – they also lengthen the total time throughout the year that conditions are right for wildfires.[3]

Climate change is making some areas drier than before. Precipitation in the Southwest is heavily influenced by El Nino; there is some evidence that climate change may be making El Nino (and La Nina) more extreme.[15] Precipitation in California is also heavily regulated by temperatures in the Pacific Ocean; warmer sea surface temperatures driven by climate change can block rain from reaching the state.[16]

How does climate change interact with forest management and land use to create wildfire disasters?

Climate change on its own doesn’t create wildfire-driven disasters - it is the combination of climate change, human land-use and forest management which can make fires more severe, and the exposure to and vulnerability of populations to that fire.[8]

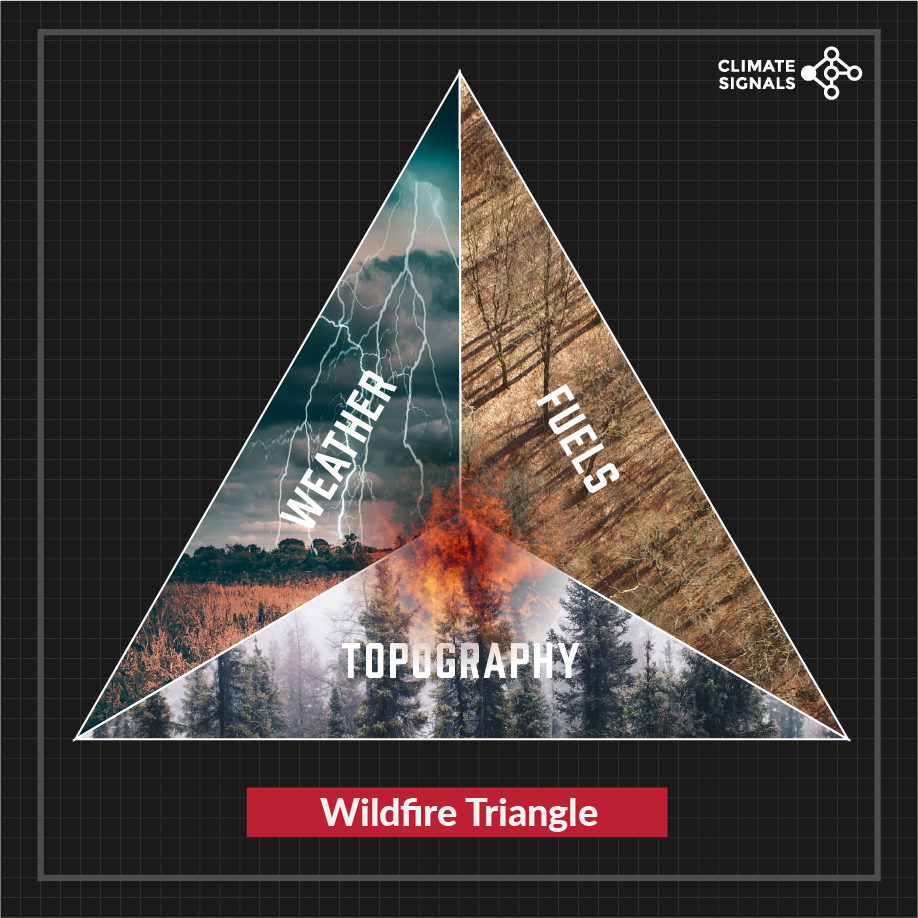

Fire officials explain wildfire behavior using the fire triangle. Wildfires are driven by three elements: topography (mountainous versus flat), vegetation (the fuel source), and weather. As topography and weather generally cannot be controlled, most fire prevention in wildlands focuses on removing dry vegetation and encouraging healthier ecosystems which won’t burn as easily. In some regions, forest mismanagement has increased wildfire risk. In ponderosa pine forests, for example, the historical use of fire suppression has led to a buildup of fuels, increasing both the risk of severe fire and the exposure of communities to those fires.

There has been more building near forests, or in woodland-urban-interfaces (WUIs), which increases how exposed communities are to wildfires – as happened with the 2018 Camp Fire. Additionally, while affluent communities tend to live in greater risk zones, communities of color and low-income communities are particularly vulnerable to fire due to lack of access to insurance, emergency fire response, and fuel removal.[17]

Human land-use practices alone cannot explain the devastating infernos of the past decade – these would not be possible without human-driven climate change. Climate change-fueled fires have dire consequences – from respiratory illness to loss of life and property - and many communities are not equipped to deal with this new era of mega fires.

Regional spotlight: Climate change & recent wildfire seasons

The world's eight most extreme wildfire weather years have occurred in the last decade, driven by a decrease in atmospheric humidity coupled with rising temperatures. Below are summaries of US trends.

Western US

In the Western US, climate change has doubled how much land has burned.[2] Wildfire frequency has quadrupled in the West since the 1980s, and fire season has increased by 78 days, changes which are largely linked to warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt.[3] Both warmer temperatures and earlier snowmelt for this region has been attributed to climate change.[4][5] Finally, climate change increased the risk of fire weather in 2015-2016 fivefold.[6]

California

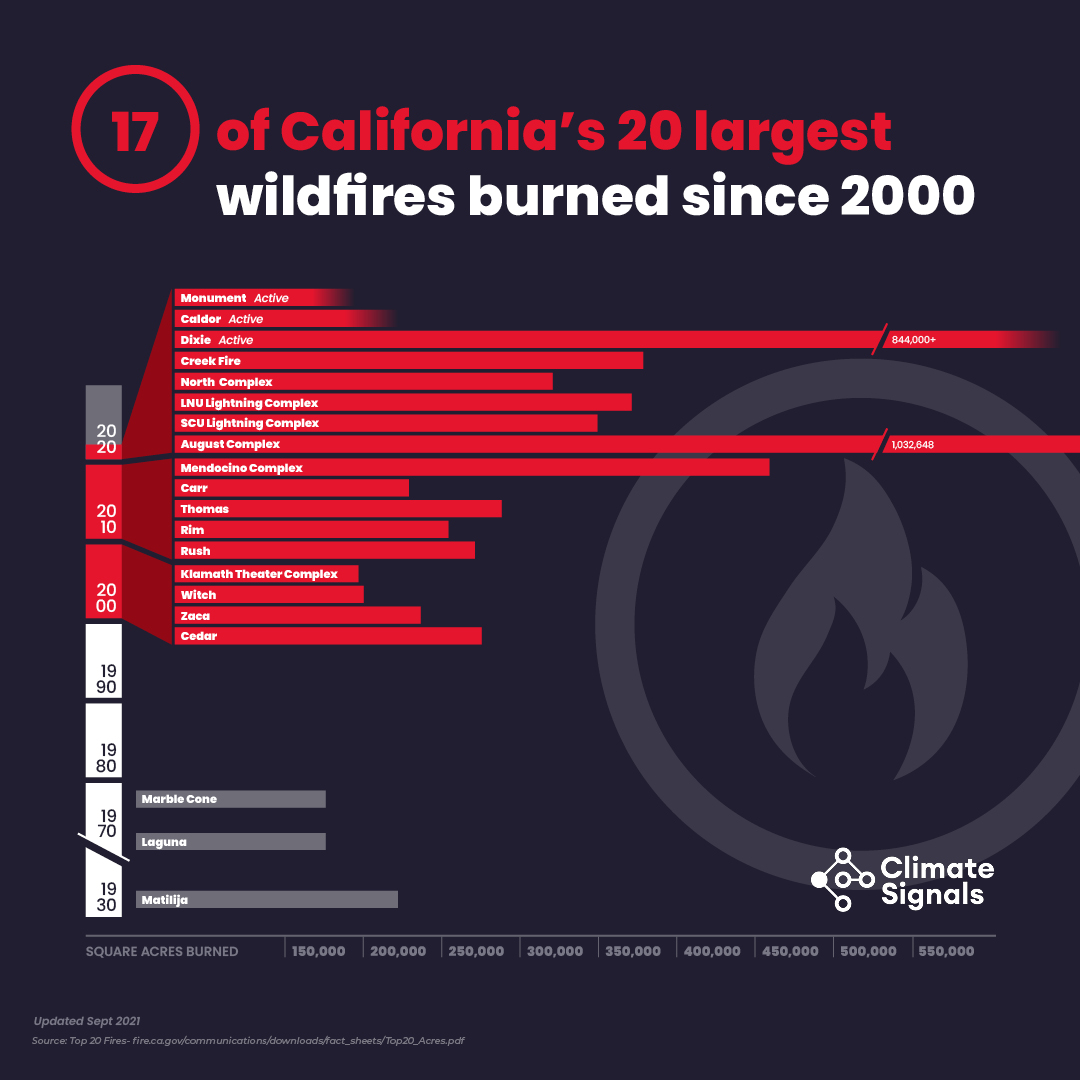

In California, climate change has increased fire risk.[7] The combination of climate change and human practices such as urbanization have increased the frequency of wildfires, particularly along the southern coast and the southwestern Sierras.[8] Increased aridity in summer and fall has increased fire activity in forested areas.[9] Climate change has doubled the frequency of autumn days with extreme fire weather conditions.[4] In urban areas in coastal Southern California, the interacting effects between urbanization and climate change have reduced summertime cloud cover, which warms and dries the surface, leading to an increase in burned area.[10] In California, 15 out of the 20 largest fires since the 1930s have occurred since 2000.[11]

Alaska

In Alaska, climate change has increased the risk of severe fire seasons by 34-60 percent.[12] Additionally, there is evidence that lightning strike frequency increases by 12 percent for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) increase.[13] In interior Alaskan boreal forests, lightning strike frequency is the main driver of fires.[14]

The social impacts of climate change and worsening wildfires in the US

Wildfires pose hazards to human health and wellbeing including cultural and economic loss, infrastructure damage, human injury and death, damage to natural resources, decreased air quality, and decreased water supply and quality.

In 2018, the Camp Fire in Northern California was the costliest, deadliest, and most destructive on record, costing an estimated $16.5 billion, killing 85 people, and destroying more than 18,000 structures.

Exposure to air pollution from wildfires is associated with exacerbating asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

As climate change makes wildfires more frequent and destructive, they are increasingly leaving in their wake debris and toxic runoff that are polluting rivers and water supplies.

Worsening wildfires driven by climate change intersect with America’s legacy of racism, economic exploitation, and environmental injustice to compound harm to poor communities, indigenous communities, and other communities of color. Native American tribes that were historically concentrated on federal Indian reserves are more vulnerable to wildfires than communities in non-reservation areas.

Most people who live in fire-prone landscapes are able to withstand the impacts due to their economic status. However, ten percent of homes are in high-risk fire zones and do not have the economic means to cope with the new era of mega fires. Families without financial means cannot afford tree trimming, brush removal, or other fire mitigation services that could mean the difference between a low severity under-burn and a severe wildfire.

Sign Up to Receive Wildfires Thought Leadership

Form temporarily disabled.