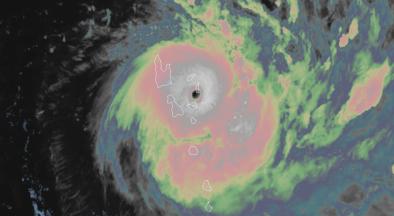

Intense Cyclone, Hurricane, Typhoon Frequency Increase

Hurricanes are fueled by ocean heat. As climate change warms sea surfaces, the heat available to power hurricanes has increased, raising the limit for potential hurricane wind speed and with that an exponential increase in potential wind damage. There is strong evidence that climate change may be responsible for the recent observed increase in the intensity, as measured by wind speeds and central pressure, of tropical cyclones.

Read More

Intense cyclone climate science at a glance

- There has been a global increase in the observed intensity of the strongest storms.[1][2]

- Tropical cyclones are fueled by available heat. Warming seas are increasing the potential energy available to passing storms, which increases the power ceiling or speed limit for these cyclones.[3]

- Higher sea surface temperatures are associated with more rapid hurricane intensification.[4]

- The fingerprint of global warming in the intensity of tropical cyclones has been identified in one ocean basin: the Northwest Pacific.[5]

- Damage incurred by tropical cyclones is overwhelmingly and disproportionately incurred by the most intense cyclone events, indicating that overall damage will increase as the climate warms.

Background information

Increase in intense cyclone strength

As seas warm and offer more heat energy, there has also been a global increase over recent decades in the observed intensity of the strongest storms. The link between warming ocean temperatures and stronger storms may be reflected in the close correlation between observed trends in recent sea surface temperatures and observed trends in the intensity of tropical cyclones.[1][6][7] The increase is well-documented and is consistent with models projecting the future climate, but the correlation between these two trends is not fully understood and scientists are still working to better understand the relation between these two trends.[3]

Fewer but stronger storms leads to an increase in overall damages

Damage incurred by tropical cyclones is overwhelmingly and disproportionately incurred by the most powerful storms, indicating that overall damage will increase as the climate warms.

Cyclone wind damage increases geometrically with an increase in speed.[8] A decrease in frequency would not be expected to offset the increase in damages incurred by increasing intensity. Moreover, damage escalates exponentially when storm strength crosses over the thresholds beyond which threatened infrastructure collapses.

We expect to see more high-intensity events, Category 4 and 5 events, that are around 13 percent of total hurricanes but do a disproportionate amount of damage. The theory is robust and there are hints that we are already beginning to see it in nature.

- Kerry Emanuel, Professor of Atmospheric Science, MIT [9]

Hurricane intensity is not the primary factor increasing hurricane destruction in a warmer climate

Sea level rise has elevated and dramatically extended the storm surge driven by hurricanes - the main driver of damage for coastal regions. Climate change has been found to have significantly increased the rainfall in tropical cyclones. Warmer air holds more moisture, feeding more precipitation from all storms including hurricanes, significantly amplifying extreme rainfall and increasing the risk of flooding.

The balance of all the factors affecting tropical cyclone activity is not fully known

Many factors affect tropical cyclones, and there is an extremely wide range of natural variability in tropical cyclone activity. While warming seas are increasing the potential energy available to passing storms, other factors affected by climate change, such as wind shear and the global pattern of regional sea surface temperatures, also play controlling and potentially contradictory roles. The balance of all these factors is not fully known.[10]

Prior periods of enhanced tropical cyclone activity say nothing about the human influence on recent trends

A reconstruction of North Atlantic hurricanes dating back to the the late 1800s adjusts the historical record in an attempt to account for hurricanes that went unrecorded in the early years, and after adjustment finds that there has been no century-scale trend. However, prior bouts of increased hurricane activity due to natural variation do not rule out a role for global warming the current period of increased activity since the early 1980s.

Global tropical cyclone trends and climate change

- There has been a global increase in the observed intensity of the strongest storms.[1]

- The link between warming ocean temperatures and stronger storms may be reflected in the close correlation between observed trends in recent sea surface temperatures and observed trends in the intensity of tropical cyclones.[1][6][7]

- In the past 30 years of ocean warming, scientists have recorded an average increase in global tropical cyclone intensity of 3 miles per hour (1.3 meters per second).[14]

- Hurricanes and other tropical cyclones across the globe reach Category 3 wind speeds nearly nine hours earlier than they did 25 years ago. In North America, storms have shaved almost a day (20 hours) off their spin-up to Category 3.[11]

- For a detailed, consensus synthesis of the science published through 2014 on climate change and tropical cyclones see, "Tropical cyclones and climate change," by Walsh et al, 2015.[3]

Most of the published scientific work concerns the expected response of tropical cyclones to climate change and anticipates that such storms will become stronger and perhaps less frequent, but at a rate that should not be formally detectable until mid-century. Yet there is clear satellite-based evidence of increasing incidence of the strongest storms, as theory dating back to 1987 predicted.[2]

- Kerry Emanuel, Professor of Atmospheric Science, MIT

Global studies attribute increases in tropical cyclone damage to climate change

(Zhang et al. 2017): In 2015, accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) in the western North Pacific was extreme, and human-caused climate change "largely increas[ed] the odds of the occurrence of this event," according to an assessment study conducted by a large group of scientists led by NOAA and published in the fifth edition of "Explaining Extreme Events from a Climate Perspective" by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.[5]

(Murakami et al. 2016): The extreme 2015 Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific hurricane season, especially around Hawaii, was not primarily induced by the 2015 El Niño tropical Pacific warming, but by warming in the subtropical Pacific Ocean. This warming is not typical of El Niño, but rather of the Pacific meridional mode (PMM) superimposed on long-term anthropogenic warming.[12]

(Murakami et al. 2016): The extremely active 2014 Hawaiian hurricane season was made substantially more likely by anthropogenic forcing. Natural variability of El Niño was also partially involved.[13]

Additional information

See the following pages for more information on specific basins:

- Visit Intense Atlantic Hurricane Frequency Increase for the climate change links to hurricane intensity trends in the North Atlantic basin.

- Visit Intense Northwest Pacific Typhoon Frequency Increase for the climate change links to typhoon intensity trends in the Northwest Pacific basin.